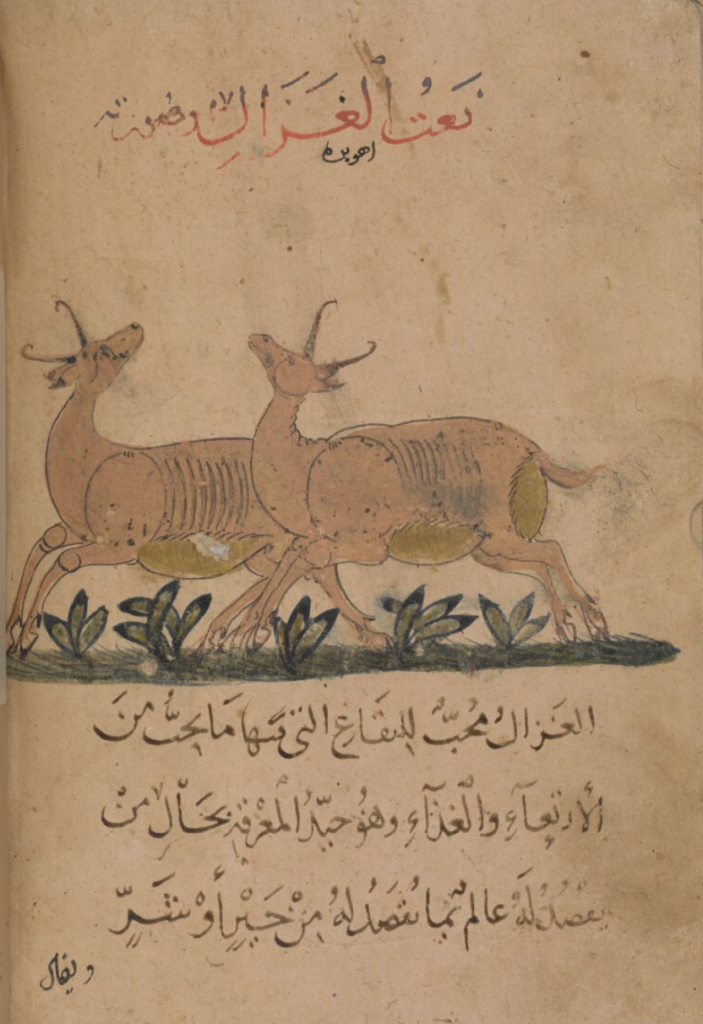

A member of the antilope family sometimes known as ‘the daughter of the sand’ (بنت الرمل, bint al-raml), the gazelle — the English word is a borrowing from the Arabic ghazāl (غزال) — figures prominently in Arabic literature with numerous references to its elegance, beauty and speed. It was sometimes known as ẓabī (ظبي), though this is the usual word for antilope. The word gazelle also has romantic connotations and often denotes a beautiful woman, particularly in poetry and songs.

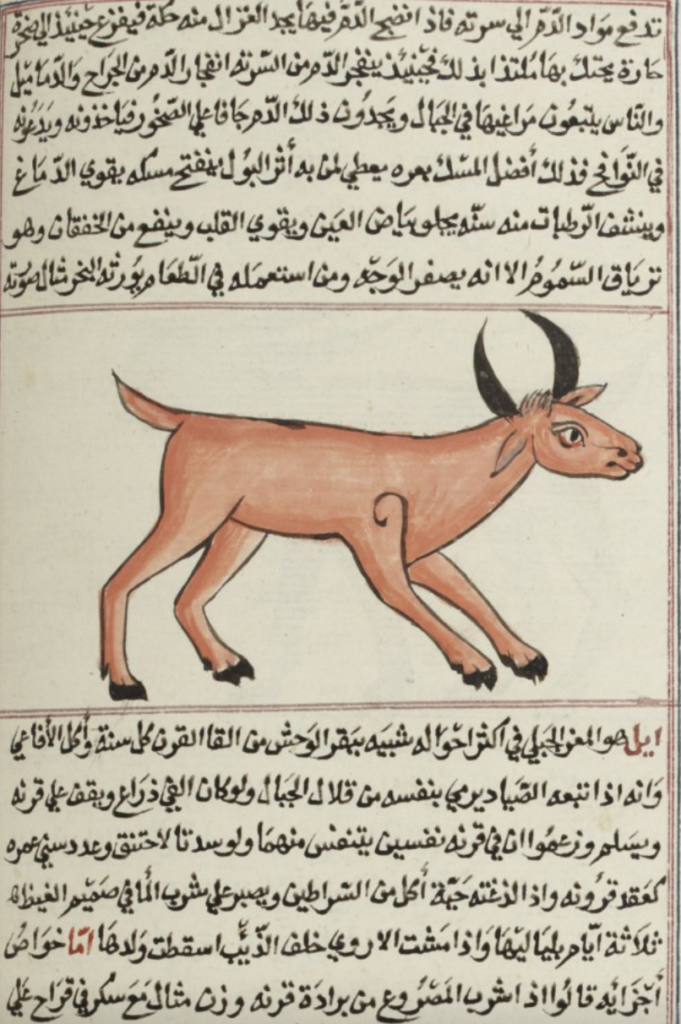

The gazelle was praised for the quality of its meat, which was the only game meat (لحم الصيد, lahm al-sayd) that met with the approval of physicians, who recommended it for old people and those with a cold temperament. The physician Ibn Butlan (11th c.) explained that if young people want to eat gazelle meat, they should let it rest overnight in pomegranate juice and vinegar. The young fawn (خشف, khishf) are better for young people and suit their temperaments. It would appear that even the heads were eaten at some point, as Ibn Butlan refers to the fact that the heads of sheep are more humid than those of goats, and those of goats more humid than those of gazelles. According to his fellow Baghdadi and contemporary, the pharmacologist Ibn Jazla, gazelle meat is useful against colic and hemiplegia.

The cosmographer al-Qazwini states that the gazelle is the shyest of all animals, but that it is very intelligent as it enters its lair backwards so as to ensure a quick getaway when an enemy is lurking within. It was also unusual in that it was partial to the colocynth (حنظل, hanzal), unlike other wild animals, which avoid it. And when the gazelle drinks seawater and then eats colocynth, the water that flows from its mouth becomes sweet!

There is also a religious connection, with the word ḥūrīyya (the English ‘houri’), which denotes the beautiful maidens of Paradise promised to the devout Muslim in the afterlife. It is related to a word meaning ‘whiteness’ and is especially applied to the eye of a gazelle (in contrast to the deep black of its pupils), as in the expression ḥūr al-ʿīn (حور العين) — the Qur’anic equivalent being ḥūr ʿīn — meaning “having eyes like those of gazelles and of cows,” which was often applied to women.

Despite the praise for gazelle meat, it appears relatively rarely in the medieval culinary treatises, with most of the recipes being found in the Abbasid tradition (9th-10th c.), where it is used in a bārida (باردة, ‘cold dish’), with cuts of the animal being stuffed with almonds and pistachio before being cooked in vinegar and a number of aromatic spices. It would be garnished with parsley, rue and mint before serving. Other recipes include frying the meat, or cooking it in a water-and-salt stew (ماء وملح, mā’ wa milh) with chickpea and onions, as well as mustard and verjuice.

In the Muslim West, only The Exile’s Cookbook mentions gazelle meat, in a stew which could also include several other wild animals such as deer, bovine antelope, mountain goat and even ass, with chickpeas, citron, garlic, onion and fennel being the main non-meat ingredients.