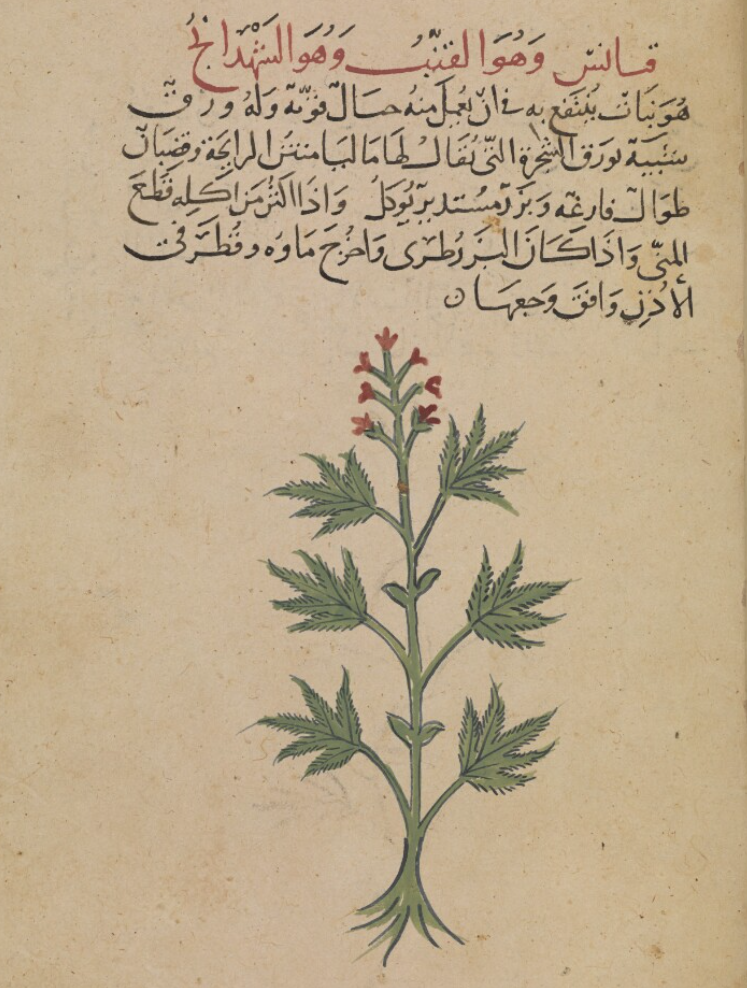

Hemp (cannabis sativa) is a member of to the cannabis family, but contains very little THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol), the psychoactive constituent, and does not produce any of the effects associated with cannabis. Its use for its psychotropic properties (especially the seeds), as well as for making ropes (from the fibre) and, less commonly, in food goes back several millennia, and is attested in ancient Mesopotamia and Iran.

In Arabic, it is known as shahdānaj (شهدانج) — though technically this denoted only the seeds — or qinnab (قنّب). Both words are borrowings from Persian, the former meaning ‘hemp seed’, and the latter (from the Middle Persian qanab), ‘hemp (rope)’. The 11th-century polymath al-Biruni traced the word back to the Persian shāh dānah, ‘the royal grain’.

As an ingredient in cooking, hemp seeds were used quite sparingly, and are not found at all in mediaeval Andalusian and North African treatises. In the earliest recipe book (10th century) from what is today Iraq, hemp is called for in only three recipes (two for seasoned salts) and one for nougat (ناطف, nātif). Later on, the seeds (often toasted) are almost exclusively associated with turnip pickles, in a couple of recipes from Egypt, the most recent from the 15th century. The only exception is a 13th-century Syrian recipe for a rich multi-seed nutty bread, which, so the author informs us, was also known by ‘the Franks (الإفرنج, al-Ifranj) and the Armenians’ as iflāghūn (إفلاغون). This term is probably a transliteration of the Greek plakous (πλακοῦς) — or its genitive form, plakountos (πλακοῦντος) –, which denoted a type of cake, whose main ingredients were cheese, honey and flour.

In Greek Antiquity, hemp was known for its anaphrodisiac — i.e. libido-reducing — qualities, and was often eaten at the end of the meal, alongside the so-called tragemata (τραγήματα), chewy desserts (mainly dried fruits and nuts), which also accompanied wine, like our present-day ‘nibbles’ .

The infrequent use of hemp seeds in mediaeval Arab cuisine may have something to do with the fact that its consumption was discouraged by physicians. According to Ibn Sina (Avicenna), for instance, hemp seeds are highly flatulent, difficult to digest, harmful to the stomach, and cause headaches. In order to alleviate these harmful effects, Ibn Jazla recommended eating the seeds with almonds, sugar and black poppy seeds, and drinking oxymel afterwards. Al-Razi (Rhazes) added that hemp blurred the sight and advised against having sour fruits or cold water after eating it. However, Ibn Sina advised hemp seed oil as a treatment for dandruff.