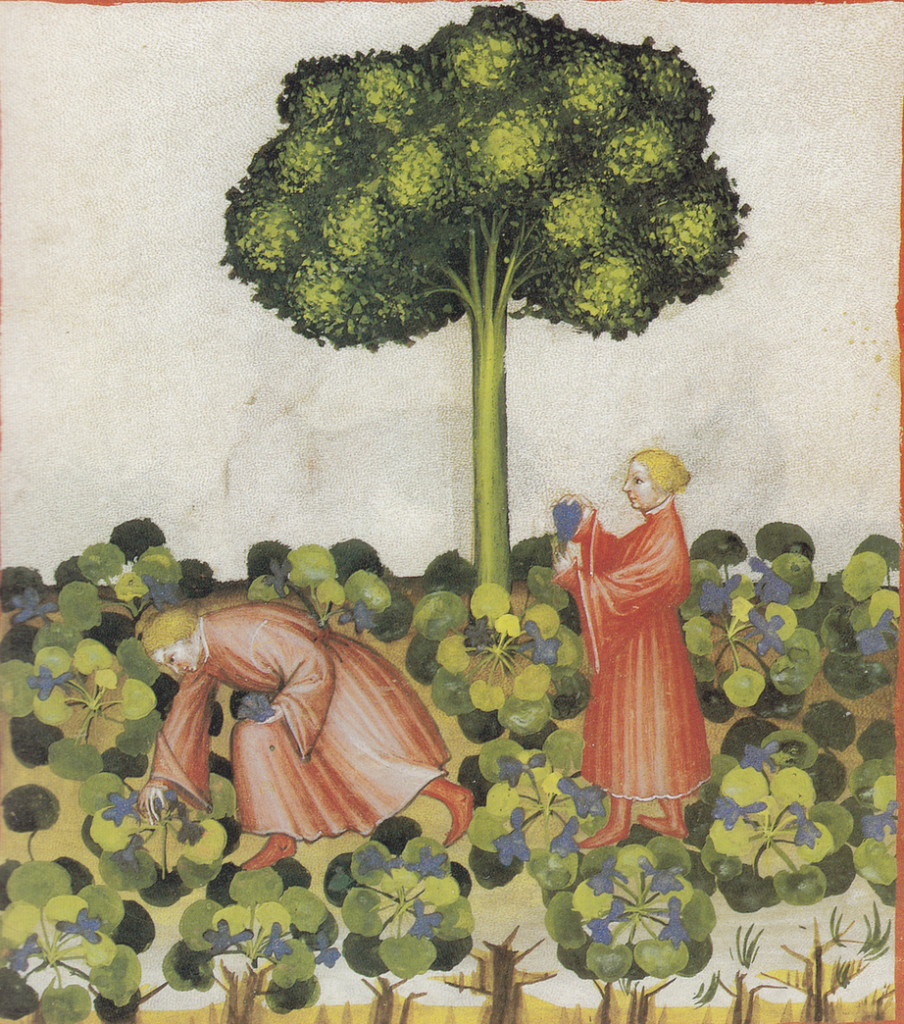

The product of the honey-bee (Apis mellifera), honey has played a very important part in both Arab cooking and Muslim culture and was the main sweetener in the medieval culinary tradition until the advent of sugar cane. At the tables of the elites it came under threat from sugar since the latter was more expensive and thus more prestigious. Honey was gathered from the wild, as well as through bee-keeping, which was already practised in Ancient Egypt, by the third millennium BCE.

In ancient Mesopotamia, honey (known as dishpu in Akkadian) was used in a variety of ways, as a sweetener (for instance in bread), in perfumes, and for medicinal purposes; for instance honey mixed with oil and beer as an emetic, or mixed with other medicines and ghee for use as ear and eye drops. It was also used in the anoinment of priests and consecration of buildings

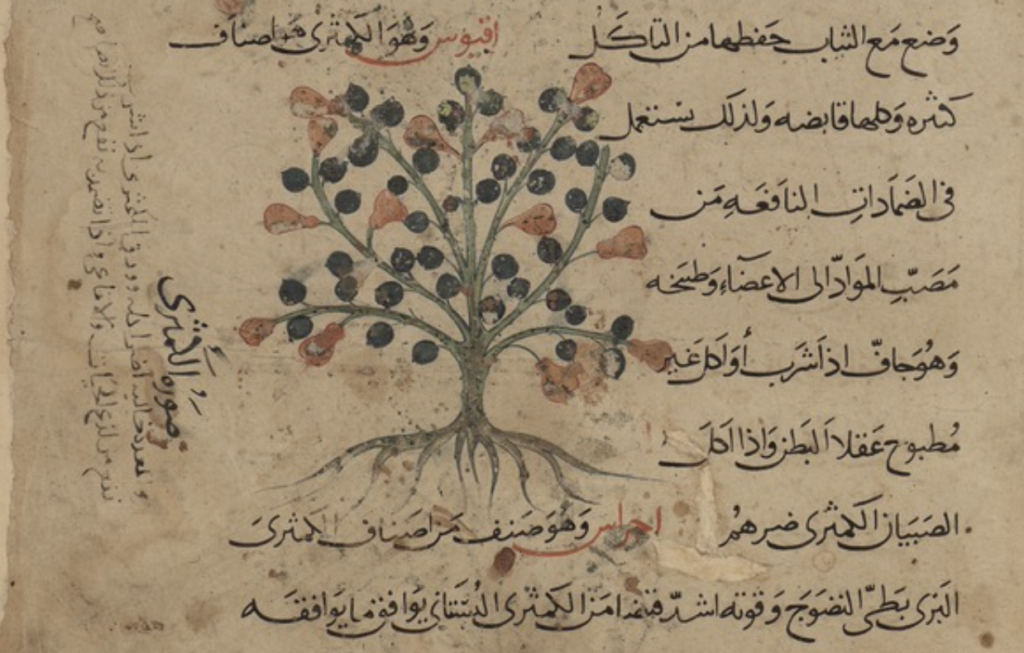

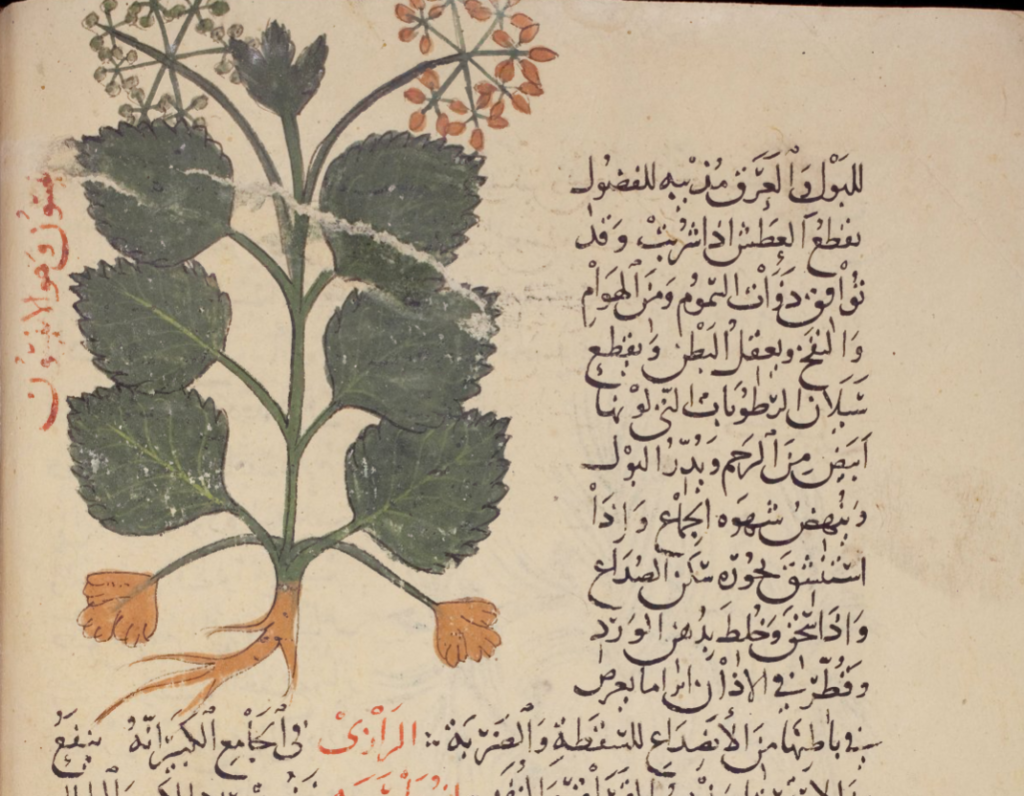

Muslim physicians, like Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna), believed honey starts as a vapour that becomes a viscid dew in flowers, plants and trees, and is gathered by bees, who feed on it and store it. The best kind of honey was thought to be naturally sweet, fragrant, slightly pungent, and red in colour. The honey gathered in spring is better than that in summer and, especially, winter, which is of poor quality. Honey was endowed with a number of medicinal — especially antiseptic — properties. Applied externally, it stops putrefaction of the flesh, cleanses ulcers, heals wounds, and improves hearing. When mixed with musk it forms an effective eye-lotion for curing cataract and other eye infections. As a food, it was considered very nutritious, while strengthening the stomach, increasing appetite, and curing dim vision.

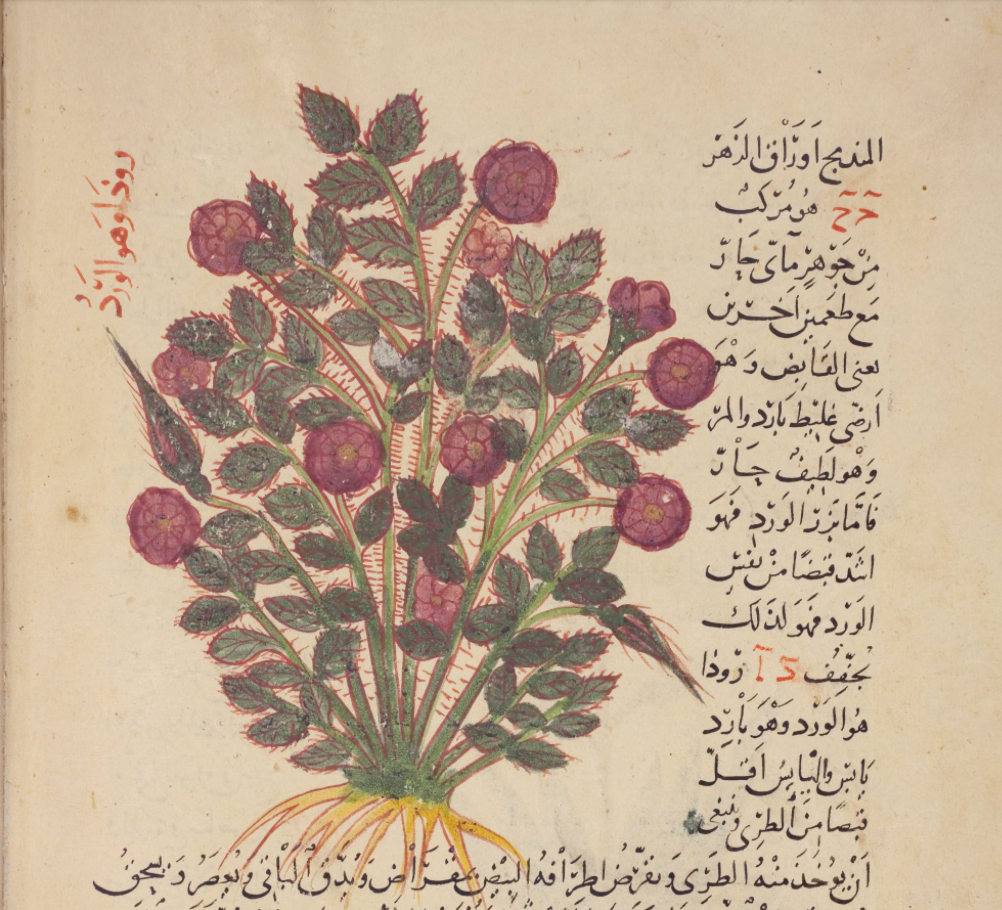

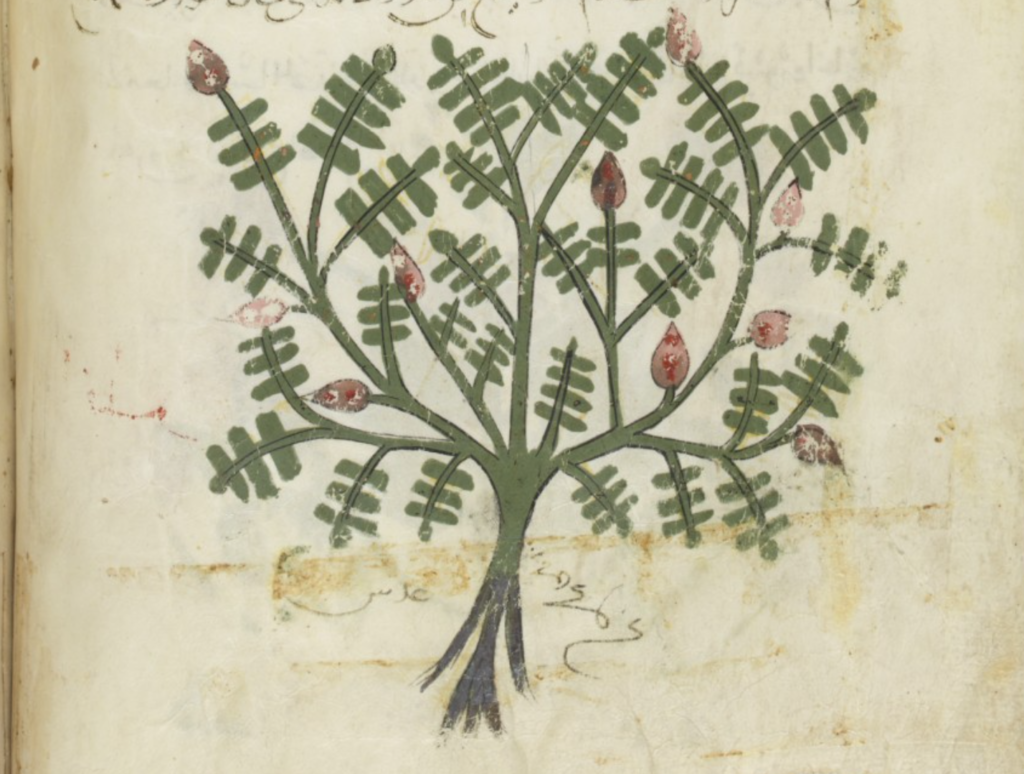

The most-prized honeys were those from the honey mimosa (Acacia mellifera) and wild lavender (Lavandula vera) flowers, while Armenia, Morocco, Persia and Egypt were popular honey-producing regions. The pure white honey from Isfahan was a particular favourite at the court of the Abbasid caliphs, and during Harun al-Rashid’s reign, the city would sent 20,000 pounds of honey and 20,000 pounds of wax as part of the tax levy to the ruler.

Honey also enjoyed a religious endorsement in that its benefits – and those of bees, of course – are already mentioned in the Qur’ān (one of its suras is called al-Nahl/النحل, ‘The Bees’) and also figure prominently in hadiths (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad). Indeed, it is said that ‘The believer is like a bee which eats that is pure and wholesome and lays that which is pure and wholesome. When it lands on something, it doesn’t break or ruin it.’ (إِنَّ مَثَلَ المؤمِنِ كَمَثَلِ النَّحْلَةِ أَكَلَتْ طَيِّبَاً و وَضَعَتْ طَيِّبَاً و وَقَعَتْ فَلَمْ تَكْسِرْ و لَمْ تُفْسِدْ).

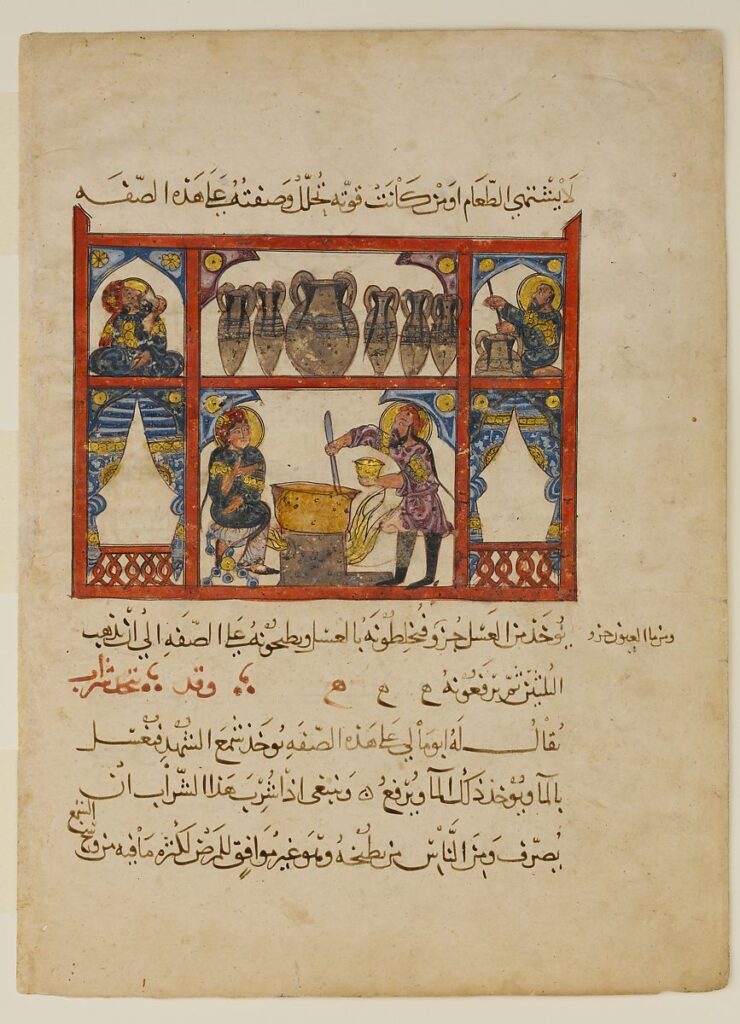

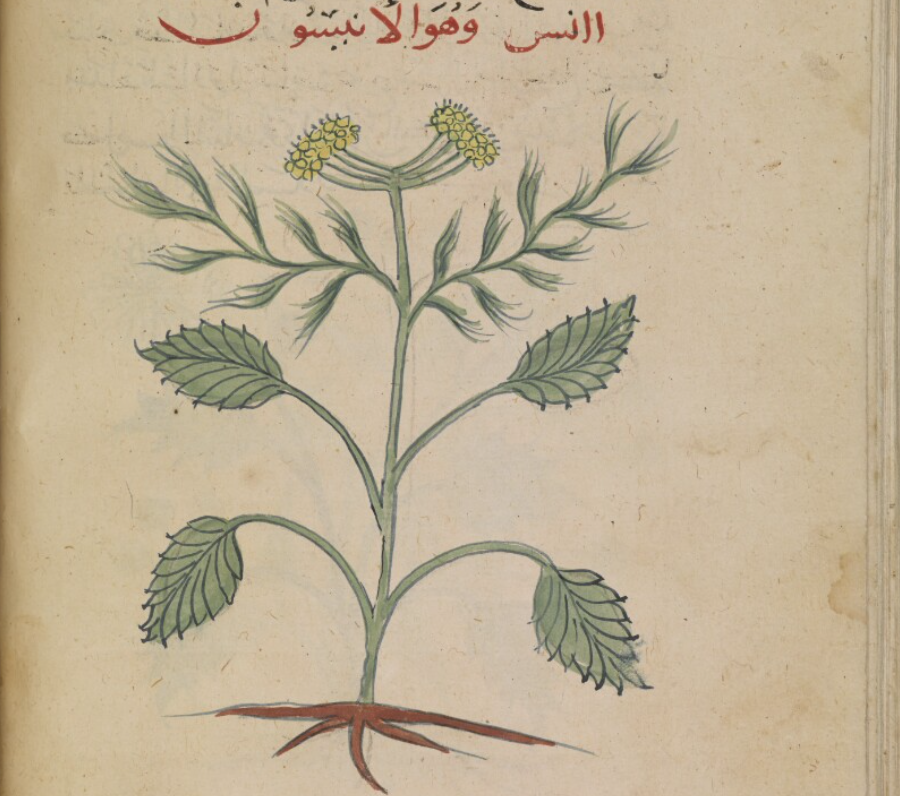

The first illustration below is part of an Arabic translation (dated 1224) of Dioscorides’ (d. ca 90 CE) pharmacological work, De materia medica. It shows a physician stirring a pot containing a mixture of honey and water, called melikraton (μελίκρατον) in Greek and maliqratun (مالقراطن) in Arabic, and serving some of it to a patient in a gold goblet. The scene is probably set in a hospital, with the section at the top showing pharmacists preparing medicines. The text is part of a passage about the mixture (the Arabic word used is sharāb, i.e. ‘syrup’) when it is old, in which case it is beneficial for those who have lost their appetite or are weakened. The Arabic text is somewhat corrupted since it refers to mixing one part of honey with honey, rather than with stale rain water, as it does in the original Greek. The mixture is boiled down to a third, and then stored. Next, we learn that some people use the term abūmālī (the Greek apomeli) for the mixture made by washing honeycomb with water. However, it must be unadulterated and, while some people boil this down, too, it is unsuitable for the sick because it contains too much beebread.

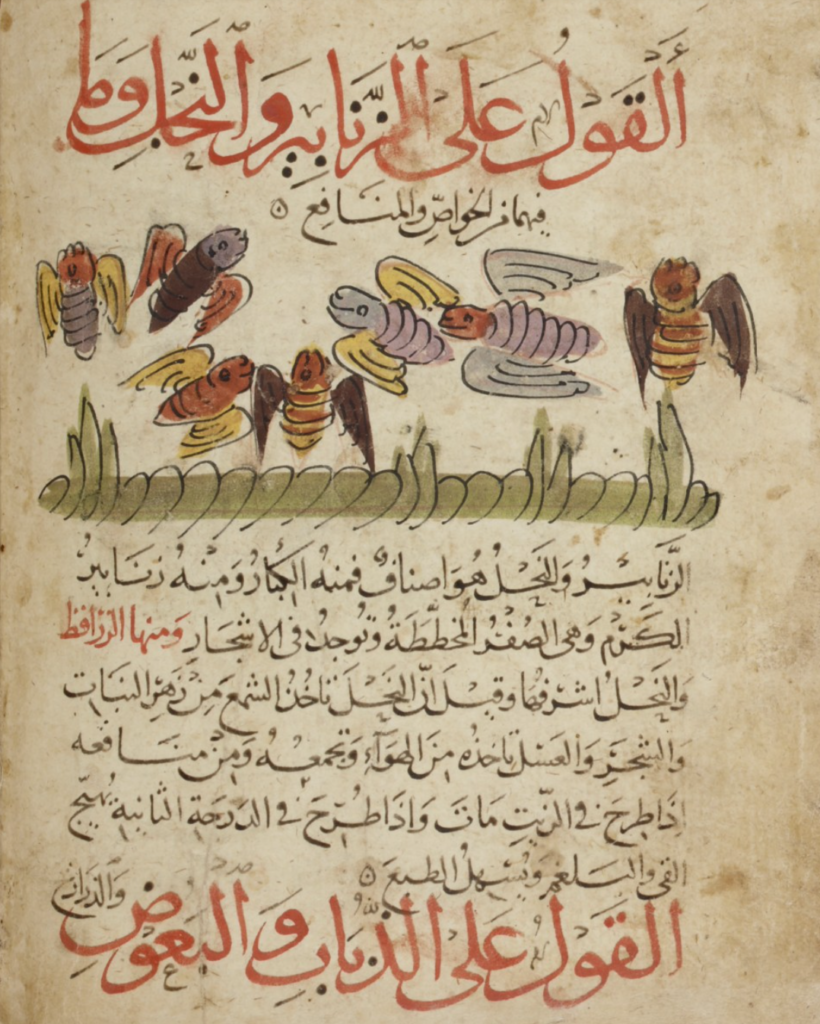

The second illustration is from the section on bees (and hornets) in a 13th-century manuscript of a book on the characteristics of animals (Kitāb na’t al-hayawān), composed by a member of the Ibn Bukhtīshū’ family, a Nestorian Christian medical dynasty, whose members served as private physicians to many Abbasid caliphs between the 8th and 11th centuries.