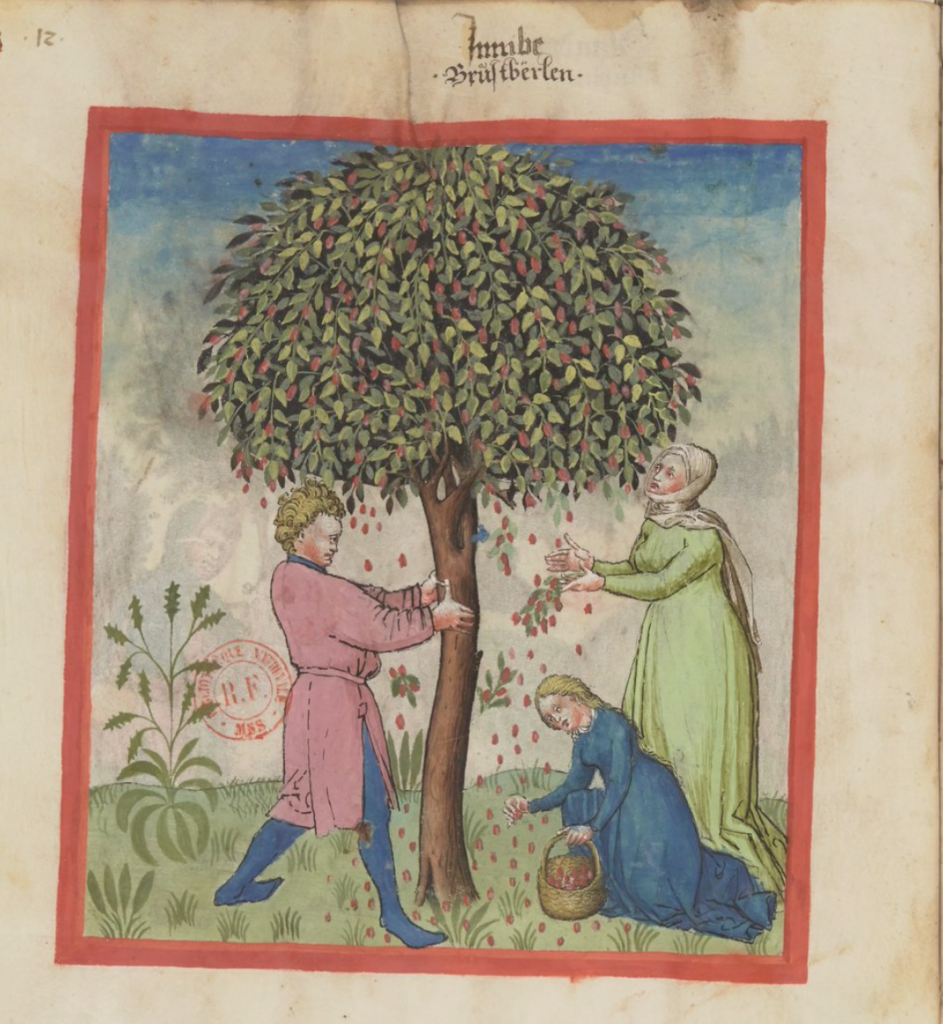

The Mediterranean basin is home to several species of wild asparagus, while the garden variety (Asparagus officinalis) was already appreciated in Roman times. Apicius recommended drying it before boiling, and included an asparagus pie in his recipe collection. The sixth-century Byzantine physician — and author of a famous culinary treatise — Anthimus recommended eating it with salt and oil. On the British Isles, the Anglo-Saxons used it for medicinal purposes only; it would take until the 16th century for the vegetable to appear on English tables, albeit very rarely until the 17th century.

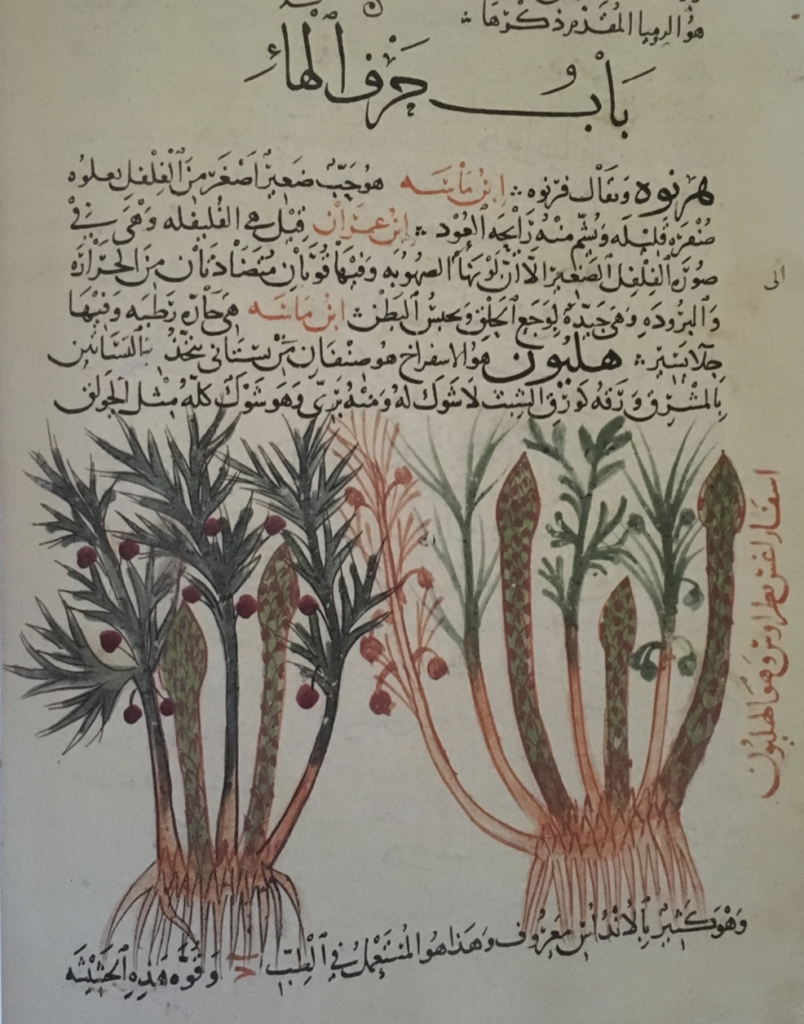

In medieval Arab cooking, there are only a few recipes requiring asparagus (هليون, hilyawn). It seems to have been highly prized though, and the author of what is considered the earliest Abbasid treatise includes a poem in praise of the vegetable. He recommends eating asparagus boiled and seasoned with olive oil and with murrī, which appears to have been the most usual way of serving it. The same source includes a few stews containing asparagus and, more unusually, an aphrodisiac asparagus drink. A 13th-century collection from Aleppo includes a recipe combining fried eggs and asparagus, a precursor to the modern scrambled egg dish.

The asparagus is conspicuous by its absence from the Egyptian repertoire, but was quite popular in al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), where it was eaten with olive oil and vinegar, or as an ingredient in meat stews. The asparagus would also be served with hard-boiled eggs, or wrapped with meat. The vegetable was introduced into the Iberian Peninsula in the ninth century by the most famous exile from the East, the singer and aesthete Ziryab. In Andalusian and North African Arabic it was known as asfarāj (أسفراج), a word derived from its Latin name, asparagus.

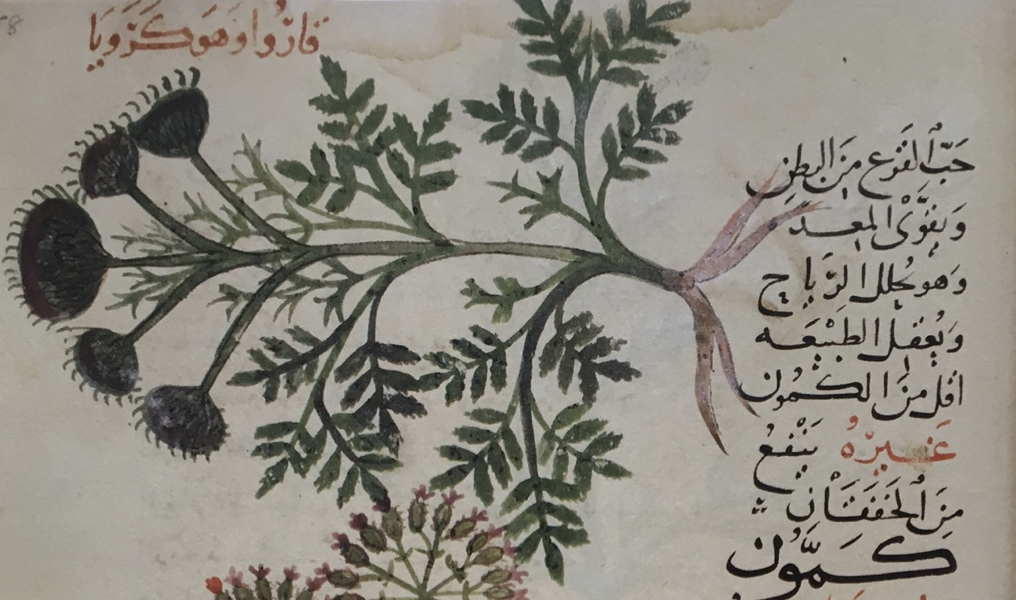

In the medical literature, asparagus was identified as a powerful aphrodisiac, as well as being a diuretic (as it had been in Greek sources), and useful against bowel blockages, sciatica, and colitis. When it is cooked with syrup, it is good for bites, but a decoction of asparagus is lethal to dogs!