Besides an open fire, food was heated in a number of devices in medieval times, and the cookery books mention several of them. A first group includes the mustawqad (مستوقد), which is only mentioned in the oldest Abbasid manual (10th century), where it is described as a stove built in the form of a trapezium (munharif), half a man’s height tall, with openings to let the smoke out. The kānūn (كانون) was a (portable) brazier, which appears a few times in manuals from both Egypt and Iraq, for the smoking of olives, for toasting bread topped with condiments and eggs (a kind of pizza avant la lettre, if you will), and, in one case, to heat up a harisa (meat porridge). It is possible that there were two types of kānūn, since the instructions for the smoked olives refer to their being placed inside and the door being closed. In Muslim Spain, khubz kanuni (‘kanun bread’) referred to bread baked in embers. In modern Egypt, the kānūn refers to a clay or mud-brick hearth for cooking.

In terms of ovens, there were essentially two kinds: the (mud-)brick furn (فرن) and the clay tannūr (تنّور), what is today called a tandoor. The latter goes back to the Babylonian tinuru, and is shaped like a cylinder or bee-hive, with a vent at the bottom (where the fire is kindled) and a hole on top. Already in Babylonian times, it was used to bake bread — most commonly unleavened –with the dough being stuck along the sides. However, in medieval Arab cuisine, it was also used to cook dishes, which would be put inside for slow-cooking after bread baking, placed on top, or even hung inside. Some of the commercial and palace tannūrs were so big that they could accommodate a whole lamb.

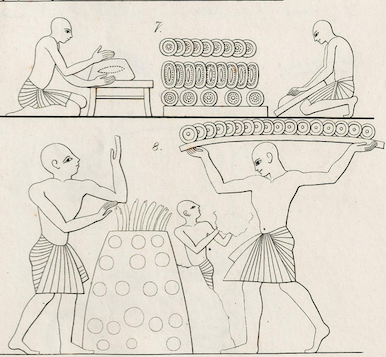

The tannūr can be found across the eastern mediterranean very early on as there is evidence of similar cylindrical ovens made out of mud and clay being used in ancient Egypt, as the illustration below shows, with loaves also being stuck along the sides for baking. In fact, the tannūr may just as easily have originated in Egypt, and then spread to Mespotamia.

The conventional oven, furn, is open at the front, with a fire being lit either inside, or underneath a shelf. It was used for baking bread, as well as for the roasting of dishes. The medieval furn would have looked very similar to the one depicted in the late 18th century in the Description d’Egypte.

But was every kitchen equipped with these devices? Well, for a start, only a small percentage of houses had a separate kitchen space, which was the preserve of the elite, some of whose houses even had two kitchens; one with an oven and a kānūn, and another one — without equipment — possibly for prepping the food. However, the Egyptian historian al-Jabarti, writing about the second half of the 18th century, explained that every notable’s house had two kitchens, “one on the lower level for men, and the other in the women’s quarters (harem).”

The average person’s house in urban areas would have had neither the space nor the required ventilation. Indeed, unlike in colder climates, fires were not lit inside since, for the most part, heating was not required, in light of the climate. Another factor was the relatively high price of fuel (wood, in particular), which was outside the reach of the majority of the population. They would, in fact, get all of their hot meals outside, which explains the huge number of public food vendors and stalls. Sometimes, people would prepare some food and have it heated up elsewhere; this was the case for bread, for instance, where the dough would be prepared at home and then sent to a communal oven, as is still the case in some areas today. However, as the cookery books reveal, this practice would also exist for other dishes. A contemporary example can be found in Marrakech, where many families still prepare the famous tanjia in traditional clay jars before sending it to be slow-cooked in the ashes of the communal oven that heats the hammam.

People living in the countryside were not faced with the city-dwellers’ problem of space, and would have had self-made ovens, made of mud, which would not have been very different from those found to this day in some rural areas. There is also evidence that they would have had makeshift outside tannūrs, the average one being approximately one metre in height, and packed with pottery on the outside to preserve the heat.

The English traveller Edward Lane, writing in the early 19th century, described the situation in Egypt at the time: “in the houses of the peasants in Lower Egypt, there is generally an oven (“furn“), at the end furthest from the entrance, and occupying the whole width of the chamber. It resembles a wide bench or seat, and is about breast-high: it is constructed of brick and mud; the roof arched within, – and flat on the top. The inhabitants of the house, who seldom have any night-covering during the winter, sleep upon the top of the oven, having previously lighted a fire within it; or the husband and wife only enjoy this luxury, and the children sleep upon the floor.” For fuel, they used dung of cattle, kneaded with chopped straw, and formed into round flat cakes, known as gilla (جلّة), which can still be found in rural Egypt.