There has been more press coverage and interviews to mark the release of The Sultan’s Feast, with reports in the Spanish daily La Vanguardia, the largest Argentinian newspaper Clarín, and Swissinfo.

Bringing Medieval Arab Cooking to Life

There has been more press coverage and interviews to mark the release of The Sultan’s Feast, with reports in the Spanish daily La Vanguardia, the largest Argentinian newspaper Clarín, and Swissinfo.

This aromatic (Cinnamomum cassia) is also known as Chinese cinnamon, in reference to its place of origin. The bark of the tree was already used in Antiquity in medicines and perfumes, though rarely in food. Ancient scholars believed it came from Arabia. Its preciousness was enhanced by its inaccessibility, which early on became legendary. The Greek historian Herodotus, for instance, recounts that cassia grows in a shallow lake guarded by bat-like creatures which attack the eyes of those cutting the plant. The Arabic term is derived from the Persian dār chīnī (دار چينى, ‘Chinese wood’) and was sometimes used interchangeably with salīkha (سليخة), but could also refer to ‘true’ (or Ceylon) cinnamon (قِرْة, qirfa). It is, in fact, not certain at all whether the present-day distinction between the two existed at the time. Some scholars only distinguished between dār ṣīnī and a qirfat dār ṣīnī, the latter being less powerful, and imported from China. In Arab cooking, it was one of the most widely used spices, and appears much more frequently than qirfa. Although often ground, recipes sometimes call for sticks (i.e. bark strips). A number of varieties (black, white, greenish, were known. Medicinally, it was used, among other things, to improve dim vision, as a cough remedy, diuretic, and even antidote against scorpion poison. Cassia differs from Ceylon cinnamon in its more reddish colour, rougher texture and stronger, more bitter taste.

A delicately perfumed salt blend from 10th-century Baghdad, named after the Iranian province where it was allegedly invented. It is made by boiling white salt and red wine vinegar, and then adding dried pomegranate seeds, sumac, nigella seeds, sesame seeds, hemp seeds, and asafoetida. This aromatic mixture is extremely versatile and can be used to season a wide variety of dishes.

For more on the recipes and context of The Sultan’s Feast, check out the interview with The Daily Star‘s Maghie Ghali, which can also be found on the leading Arabic news hub Al Bawaba.

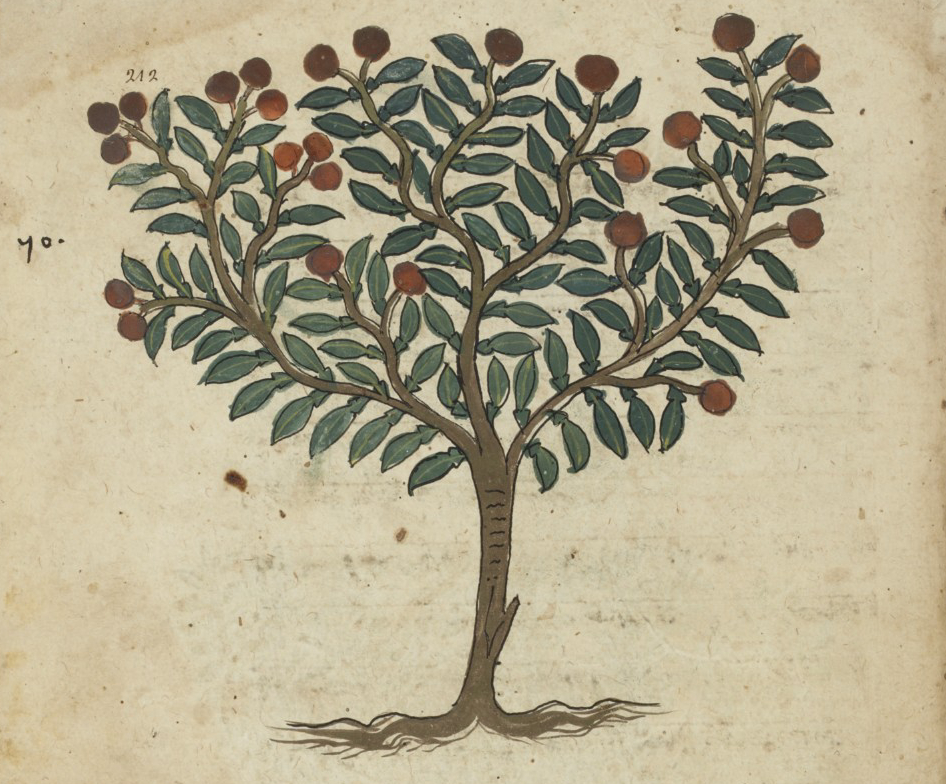

Also known as bitter or Seville oranges (Citrus aurantium), the fruit is believed to be native to China and was unknown in the classical world. The Arabic name is derived from the Persian nārang (نارنگ), which is, itself, a Sanskrit borrowing (nārañga). The fruit was introduced to Europe (in al-Andalus) by the Arabs, whereas sweet oranges (Citrus sinensis) do not appear until the end of the Middle Ages. In mediaeval Arab cooking, the sour orange tended to be used in stews. The 13th-century Andalusian botanist Ibn al-Bayṭār reports that the orange had very green leaves and white blossoms, while the flesh of the fruit is as sour as citron. It was also used to produce an oil which dispels winds and strengthens the joints. The peel strengthens the heart. When the orange juice is drunk with hot water, it is good for gripes, and useful against stings of scorpions and many reptiles. However, the pulp on an empty stomach weakens the liver. His fellow Andalusian Ibn Khalṣūn (14th c.) added that the best variety was large and sweet, and that it should be eaten with sugar. Confusingly, the 12th-century Baghdadi pharmacologist Ibn Jazla equated nāranj with coconut (jawz hindī).

These are two variations of preserved lemon from a 15th-century cookery book. The first requires taking salt-cured lemons and stuffing them with ginger, mint, and rue, before cramming them in a container. Saffron and honey are added later. The second type is a bit more tricky as the lemons should be layered on a platter and pressed down with stones, and left for three days. In both cases, the container is sealed with olive oil.

The Arabic word for this spice (Nigella sativa) is a borrowing from Persian. The aromatic seeds, also known as ḥabba sawdā’ (حَبَّة سَوْداء, ‘black grain’), were often sprinkled on top of bread loaves before baking, but are also found occasionally in some spice mixes and savoury meat dishes. In Persian, it could denote sesame, coriander or pepper. Medically, nigella was thought to be carminative, purifying, and useful against warts, freckles, ulcers, and even spider bites! However, physicians warned that the excessive use of the spice is fatal. According to the 11th-century polymath al-Bīrūnī, droplets of nigella oil serve to treat paralysis and tetanus. For those wishing to grow their own, nigella is a very hardy plant and even thrives in the inhospitable climate of Northeastern England.

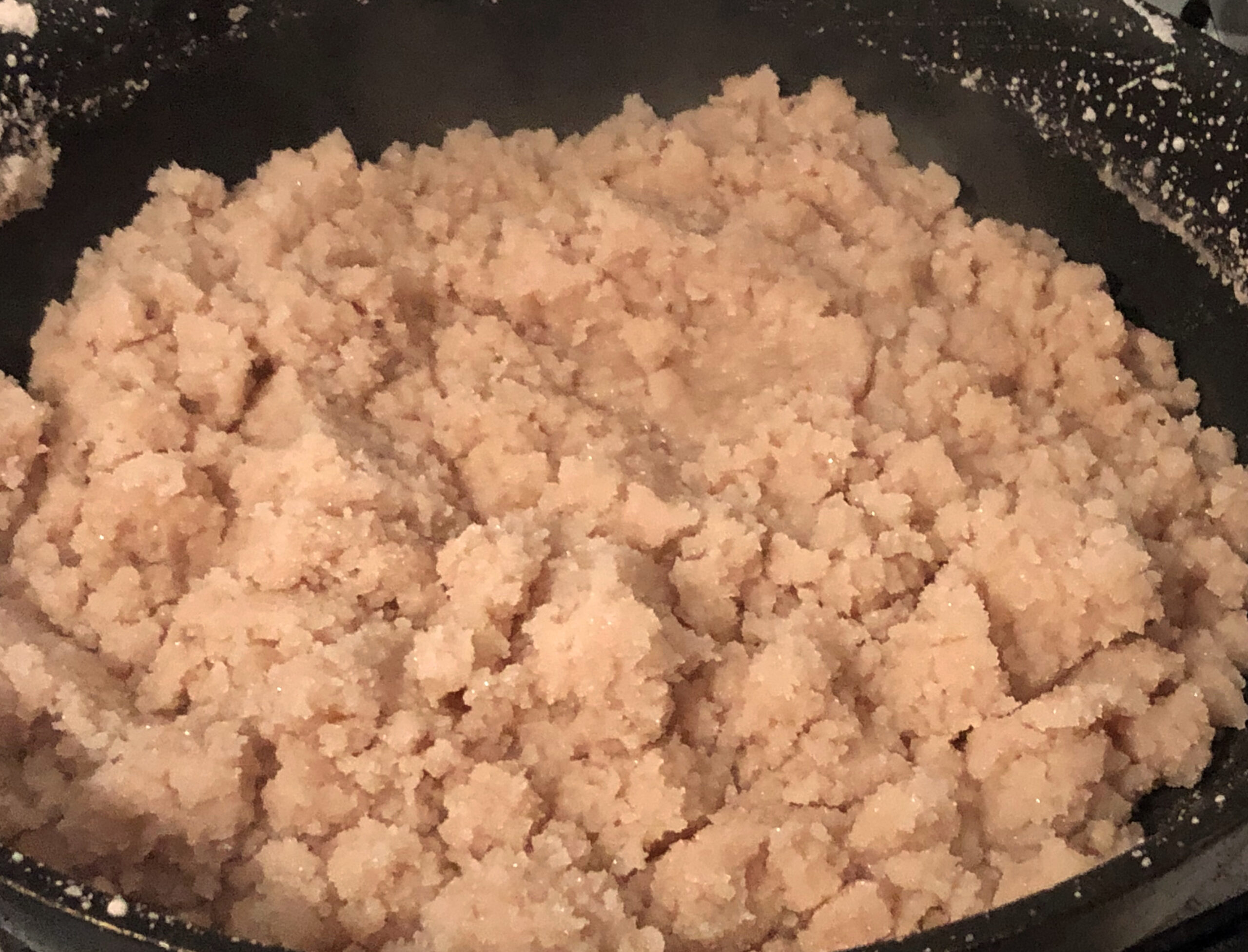

The tharīd (ثَرِيد) is one of the oldest and most popular dishes in Arab cuisine and usually denotes crumbled bread in a meat or vegetable broth. Deriving its name from the verb tharada (ثَرَدَ), ‘to crumble’, the dish was apparently one of the favourite foods of the Prophet, himself, who reportedly said that “the virtue of ʿĀ’isha [his favourite wife] among women is like that of the tharīd among all food” (فضل عائشة على النساء كفضل الثريد على سائر الطعام). This 13th-century recipe is attributed to a Cordoban physician by the name of Abu ‘l-Hasan al-Bannani, who would apparently make it in spring. It is prepared with diced lamb, salt, onion juice, pepper, coriander seeds, caraway and olive oil. Once this is cooked, spinach, grated cheese and butter are added, before pouring everything onto the bread crumbs. In this recreation, the dish is served with couscous.

It denotes the root of several fragrant perennial plants of the Valerian family, which are native to India’s Hymalayan region. Bitter in flavour and musky in odour, spikenard (Nardostachys jatamansi) was already known in Biblical times, and is mentioned in the Old Testament (Song of Solomon). It was mainly used in the form of a highly perfumed — and costly — ointment, such as the one used by Mary Magdalen to anoint the feet of Jesus. Its use in cooking is attested in Roman cuisine (in the 1st-century collection attributed to Apicius, there are two recipes requiring the spice – one for a sauce accompanying cold meat, and another for glazed venison) and Byzantine cuisine. In the Muslim world, it was one of the basic aromatic spices, and synonymous with nārdīn (< Gr. nárdos) in Arabic botanical and pharmacological works. It was used in in perfumes, breath sweeteners and the like, as well as in dishes and beverages. Islamic scholars identified a number of varieties, the most famous among them was Indian spikenard (سنبل هندي, sunbul hindī), also known as aromatic (سنبل الطيب, sunbul al-ṭīb) or sparrows’ spikenard (سنبل العصافير, sunbul al-‘aṣāfīr), which was considered the best and most potent. The medicinal uses of spikenard were already known in Antiquity; for instance, both Dioscorides and Pliny recommended it for eye diseases. In Arabic medical and pharmacological literature, it was advised for the liver and stomach, colds, skin conditions, haemorrhoids, uteral tumours, to sweeten the breath, and as a diuretic, abortifacient, and sexual stimulant. In India, its root is still used to prepare a hair perfume.