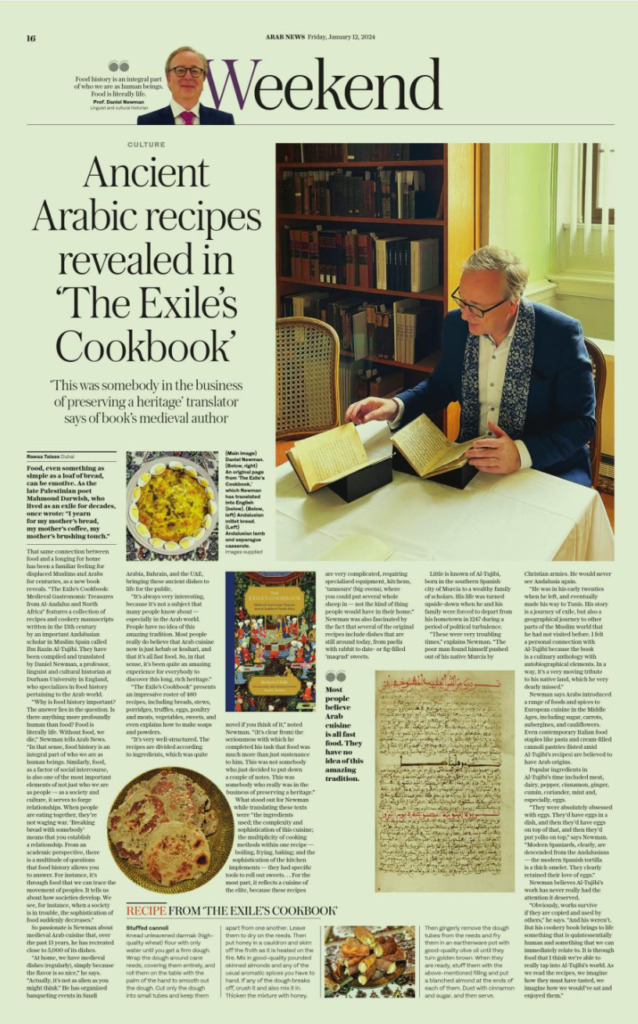

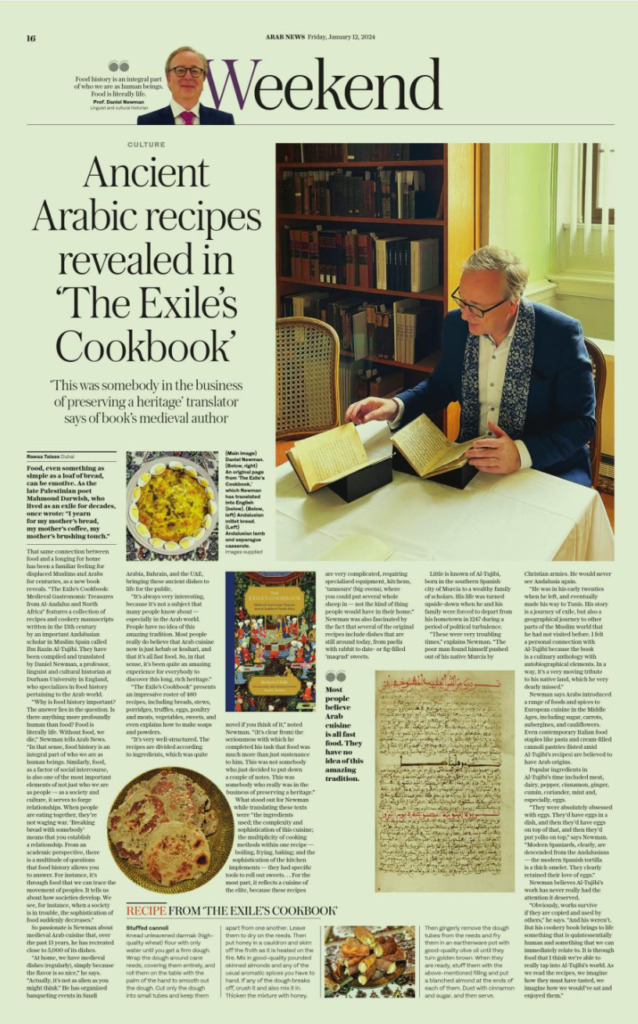

A wonderful review article on The Exile’s Cookbook and the history of Arab cuisine in the Weekend section of Arab News.

Bringing Medieval Arab Cooking to Life

A wonderful review article on The Exile’s Cookbook and the history of Arab cuisine in the Weekend section of Arab News.

This is a recreation of a 13th-century Aleppine recipe for a drink made with pomegranate seeds, fresh mint leaves, sugar and a dash of rose water. For that real medieval experience you might wish to consider fumigating the goblet from which you drink with that most aromatic of spices, ambergis! It is best drunk chilled with some crushed ice — a delightful mocktail to suit all occasions!

According to the recipe in The Exile’s Cookbook, one should take medium-sized olives harvested in October, before they become ripe. These are preserved in water and salt until they are ready for use. However, before serving the olives, coat them in olive oil and oregano. Served with some bread, they can be both a delicious snack and a light meal.

Check out the detailed coverage of the ‘Fujairah Feast’ (وليمة الفجيرة ) held on the 27th of December at the Fujairah Fort in the leading Emirati lifestyle magazine Kull al-Usra and The Khaleej Times of the ‘Fujairah Feast’ (وليمة الفجيرة ).

This month, I curated three medieval banquets in the Emirate of Fujairah in the United Arab Emirates, as part of a research project on ‘Medieval Arab Cooking: Identity and Culinary Heritage’. The events were organised under the patronage of His Highness, Sheikh Mohammed bin Hamad al-Sharqi, Crown Prince of Fujairah, who also provided generous support throughout, and in collaboration with the Fujairah Culture and Media Authority. Here are some of the highlights from some of the events, including the cooking of the most spectacular dish of the day, a stuffed camel!

An unusual sweet recipe from The Exile’s Cookbook, made with honey which is heated and stirred with a giant fennel stalk. When it cools down, egg whites are mixed in and then the mixture is heated up again until it thickens and whitens. The final ingredient is almonds or walnuts, as per one’s individual taste. It has a nougat-like consistency and is one of several Arab ancestors to various European confections.

I attended COP28 (30th November-12th December) in Dubai (UAE) to take part in an exciting project relating to food sustainability and local heritage, in collaboration with the Barakat Trust and Al Ghadeer Emirati Crafts, a pioneering project under the aegis of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Red Crescent Authority. The aim of the association is to empower local craftswomen by providing them with a sustainable source of revenue.

At the COP28 site, I curated a date tasting workshop through a number of carefully selected recipes based on the medieval culinary sources from the 8th to the 15th centuries. The dishes included stuffed honeyed dates, a meat-and-date stew (tamriyya), a milky date pudding (khabis) and a cereal-based date drink (subiya).

A unique recipe from The Exile’s Cookbook, which is also the only medieval Arabic cookery book to include recipes with tuna, in this case dried tuna. The fish is cut up and lightly fried before being cooked with pre-boiled aubergines, onion, olive oil, pepper, coriander and cumin. If one does not wish to use onion, then, so the author informs us, you can add peeled garlic, murrī and vinegar. Either way, the dish is cooked over fire and then finished off in the oven to allow it to brown. After it’s cooled down, it’s ready to eat!

However, a word of warning from the author: as fish are harmful to certain temperaments, one should drink some spice honey syrup afterwards — the recipe for that one will follow soon.

This recipe from The Exile’s Cookbook is an Andalusian twist on a classic Arab dish, which goes back to pre-Islamic times. It is made with crushed wheat — the Arabic word harīsa (هريسة) is derived from a verb meaning ‘to mash’ –, which is slow-cooked and then added with fatty veal meat and suet in order to ensure a gluey consistency. But that’s only the half of it — the author recommends keeping some of the harīsa mixture to one side and frying it into patties, which are then added on top as a garnish, together with egg yolks and — if you have any — sparrows (!). A sprinkling of cinnamon, and then it’s time to serve! If you don’t have veal, feel free to use mutton or chicken, while the wheat can be subsituted for rice. Descendants of this dish are still around today, most notably the harees (هريس) of the Gulf and the Armenian harisseh.

Believed to have originated in New Guinea in around 8000 BC, thence moving to India where it was domesticated before spreading to Iran in the 7th century. Though the ancient Greeks knew of sugar, it is uncertain whether it was the crystallized variety. There is no evidence of its use in cooking in Antiquity and Apicius’ manual does not contain any recipes requiring sugar. From Iran, sugar cane spread westward along the Mediterranean, reaching Egypt in the 8th century and al-Andalus by the 11th century.

Its origins are revealed in the terminology, with the Arabic word for sugar, sukkar (سكّر) being a borrowing from the Persian shakar (shakkar), itself a corruption of the Sanskrit sakkarā which referred to the juice from the sugar cane (قصب السكر, qasab al-sukkar) as well as hard sugar.

It was an expensive ingredient, which also enjoyed the imprimatur of physicians associated with the hospital of Jundishapur in Iran, several of whom would ply their trade at the Abbasid courts. However, the Andalusian physician Ibn Zuhr, for his part, wrote a treatise in which he expressed a preference of honey over sugar, claiming that doctors only started using sugar in all of their preparations in an attempt to pander to the rarefied interests of their patrons.

This explains why in the mediaeval Arab culinary treatises which reflect the cuisine of elite, sugar appears as the most-used sweetener in all kinds of dishes, though not infrequently in conjunction with honey, rose water and/or and rose-water syrup. The best variety of sugar was the white translucent ṭabarzad (طبرزد) which was made with milk. Other varieties included fānīd (فانيد) — made by adding sweet almond oil of finely-ground white flour to the decoction process) — and Sulaymānī (سليماني) sugar, which was produced from ‘red sugar” (sukkar aḥmar), which was broken into pieces and cooked to remove any impurities.

When making sugar, the boiled juice, called “maḥlab” (محلب, ‘milk’), was poured into cone- shaped earthenware moulds (أبلج/ublūj, pl. أباليج/abālīj), which are wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, resulting in conical sugar loaves. Sugar was sold at market with the required quantity grated, or chopped off with a dedicated axe. Culinary recipes often refer to sugar being crushed and sifted.

Medicinally, sugar was said to be laxative, purgative and is useful against excess yellow bile in the stomach. It clears blockages. Old sugar expels phlegm from the stomach, while ṭabarzad prevents vomiting.

The Arabs introduced sugar to Europe and illustration below shows the making of sugar in the late 16th-century; sugar cane is cut and heated before being cooled and cut into shapes. Sugar cane remained the source of sugar until the development of the sugar beet in the 18th century.