In the medieval Islamic world, travel was very important, whether it be for trade, education, or religion (the hajj), and conditions were often hard. As a result, it is hardly surprising that leading physicians paid a great deal of attention to the health and regimen of travellers (تدبير المسافرين, tadbīr al-musāfirīn). Ibn Sina (Avicenna), for instance, said that travellers should divide their rations into portions that are not too big and in keeping with their temperament so as to allow full digestion, whereas herbs, vegetables and fruits should be avoided (unless they are required for medical reasons) as they may produce bad ‘humours’.

Travel often meant going without food or drink for long periods of time and so one should avoid snacks that cause thirst, such as fish, capers, salted foods, and sweets. If there is a shortage of water, vinegar should be added to it, as this quenches thirst. In order better to withstand food deprivation, Ibn Sina recommended food prepared from roast livers and the like, strong liquid fats, almonds, and almond oil, whereas beef fat will help suppress hunger pangs for a long time. He recounts that one man partook of a pound of violet oil in which fat had been dissolved and felt sated for ten days. al-Razi (Rhazes), for his part, suggested chewing pickled onions as a travelling snack, since this assuages hunger. Travellers should also refrain from riding immediately after a full meal, because the decomposition of the food causes thirst.

Scholars made a distinction between travelling to hot or cold regions. When journeying in the former, Ibn Sina suggested travellers eat barley sawīq (see below) and fruit syrups before setting out since riding on an empty stomach greatly reduces one’s strength.

If one is afraid of being caught in a samūm (hot desert whirlwinds), one should eat onions with (or before) thick sour butter milk (دوغ, dūgh) or, especially, onions steeped in it overnight — the onions should be scored before putting them in the milk. Another remedy to deal with the anxiety is to suck on aromatic oils, such as rose oil or gourd-seed oil, as these have a calming effect.

Travellers in cold climes should take provisions that allow them to endure the cold more easily, and according to Ibn Sina, this includes foods with plenty of garlic, walnuts, mustard, asafoetida, which all have hot ‘temperaments’. Yoghurt whey (مصل , masl) can be added to make the garlic and walnuts taste better. Clarified butter (سمن, samn), or ghee, is also good, especially if one drinks wine after eating it. In cold regions, one should drink wine rather than water. Asafoetida, in particular, has a warming effect, especially when taken with wine.

The cookery books also sometimes mention the usefulness of certain foods for travellers, as in the case of khushkānaj (خشكانج), a type of pastry, or hays (حيس) — date balls mixed with nuts –, which are mentioned by both al-Baghdadi (13th century) and al-Warrāq (10th c.), with the latter specifying that this confection tended to be carried by the elite on the hajj.

Al-Warrāq also devoted an entire chapter on the already-mentioned sawīq (سويق) for travellers. This drink was made with toasted wheat grains (or almonds), to which pomegranates, or clarified butter could be added, and which was stored until needed, when water would be added, as well as sugar, to taste. This was already a favourite among Bedouins in pre-Islamic Arabia.

The same author mentions a type of dip, sibāgh (صباغ), which could be made from a number of ingredients, such as yoghurt, raisins, walnuts, and even fish, but often included mustard. One variety in particular was said to be good for the road since it involves kneading a mixture of pomegranate seeds, raisins, pepper and cumin into discs, which can be stored and, when needed, are dissolved in vinegar. This would be eaten with bread.

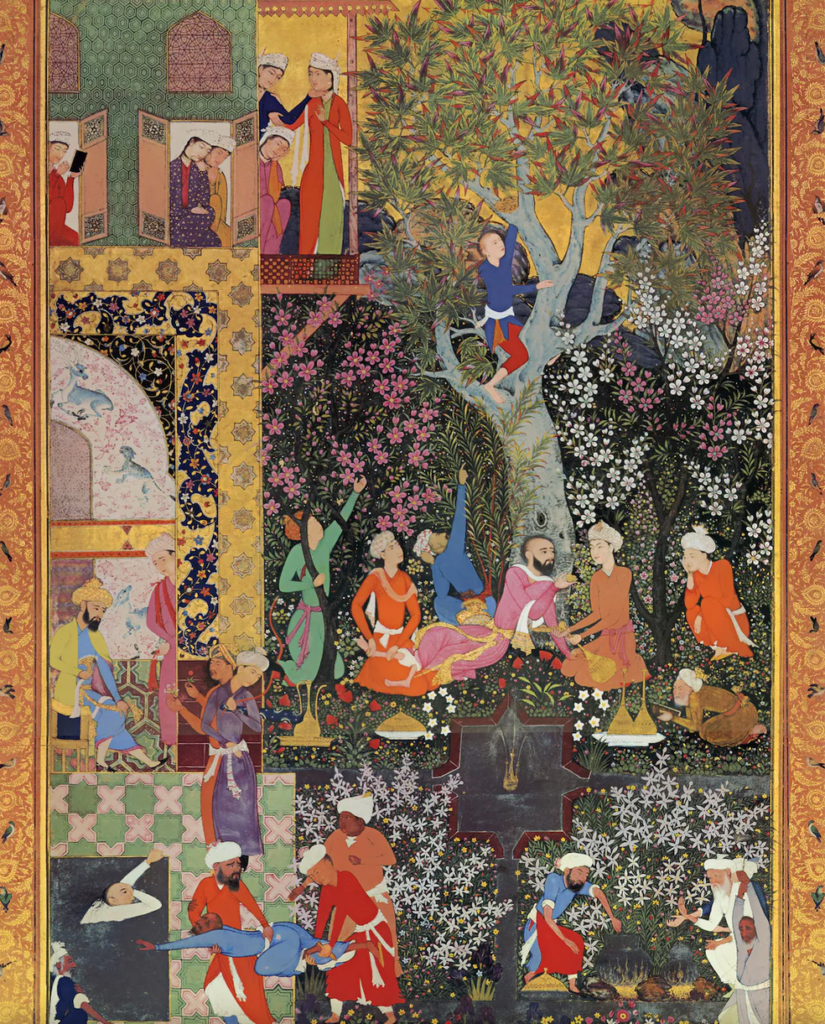

When the high and mighty travelled, they would, of course, do so with their chefs and portable kitchens, which included braziers, cauldrons, and all the kitchen- and tableware in keeping with their station. In some cases, the challenges of al fresco cooking resulted in a new dishes, as in a famous story of the development of a dish called kushtabiyya (كشتابية) about a Persian king whose Arab chef would prepare meat slices cooked on embers or boiled, eaten with a dip. One day, the cook was caught unawares by the unexpected return to camp of the king, and had not had time to start cooking the meat. In order to speed things up, he put the meat in a pan with some oil and lit the fire. He put the meat in a frying pan, poured in some fat, and fried it. He sprinkled the meat with salted water, and added some chopped onion and spices before covering the pot and letting it stew.

Travel was responsible for the creation of other dishes as well, such as kebabs which would have been skewered on a sword and roasted over a fire.