It is thought that ginger (Zingiber officinale) originated in China, though it was very early on also grown in the Indian sub-Continent. In fact, the Greek word zingiberi (ζιγγίβερι) can be traced back to the Sanskrit śṛṅgam (‘horn-shaped’). In ancient Greece and Rome it was already used in both cooking and medicine. According to Dioscorides (1st c. CE), who said ginger tasted like pepper, the plant was grown in ‘Troglodytic Arabia’ (present-day Eritrea), where people boiled it for draughts and mixed it into boiled foods. He added that it was pickled and shipped to Italy in clay vessels, in order to preserve its flavour. In Apicius’ Roman cookbook, ginger is used in a variety of recipes.

In medieval Arab cuisine, ginger (زنجبيل, zanjabīl) was a key ingredient, and was used both whole and ground, in sweet and savoury dishes (with meat as well as fish), and beverages; indeed, the Qur’an (76:17) mentions a ginger-flavoured drink as one of the beneficences of paradise. In the cookery books, ginger is used more often in Near Eastern recipes than those from the Western Mediterranean. It usually co-occurs with pepper, mint, olive oil, salt, and rose water. In Andalusian cuisine, ginger is often sprinkled on dishes before serving, alongside cinnamon and spikenard.

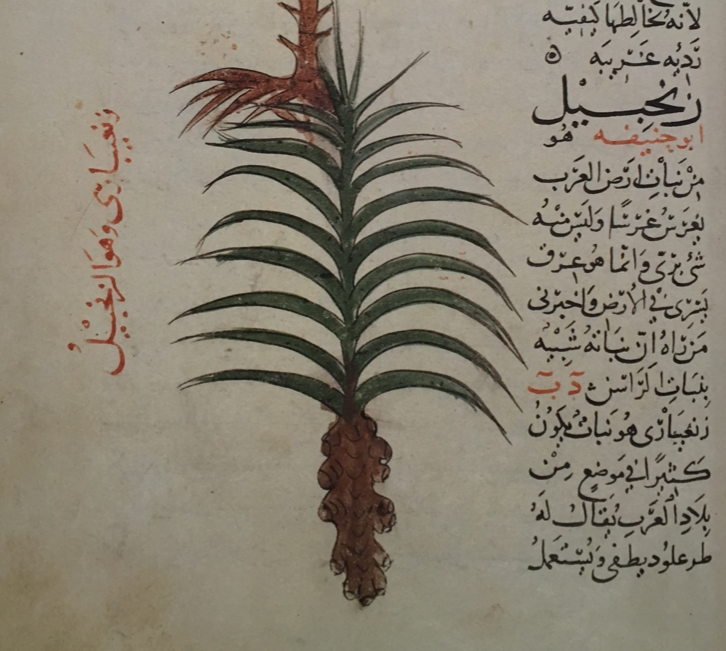

In his book on Simple Drugs (الأدوية المفردة, al-Adwiya al-mufrada), which was translated into Latin by the famous physican Arnaldo de Vilanova, the scholar Abu ’l-Ṣalt Umayya al-Ishbīlī (d. 1134) distinguished between different types of ginger: Frankish (also known as ‘Chinese’), cultivated, and Syrian, equating the last two with elecampane (rāsin). The Frankish variety “grows abundantly in Arab lands, especially Oman, where its leaves are used like those of rue and they put it in their food. (…) It tastes like pepper, and tastes and smells nice. (…) It is imported from India but also grows in the land of the Franks and al-Andalus. …. It is also called zanghibārī.”

Physicians praised its aphrodisiacal and digestive qualities. Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) said it also increased memory, and according to the 13th-century Andalusian scholar Ibn Khalṣūn, ginger has no harmful effects whatsoever, provided it is used in moderation. His compatriot, the botanist Ibn al-Baytar (d. 1248) added that it is useful against lethargy and venoms. The Persian polymath al-Bīrūnī (d. ca 1052) praised the aphrodisiac properties of ginger conserve (زنجبيل مربّى, zanjabīl murabbā), which also heats the stomach and the liver.