A delicious 10th-century Iraqi dish of carrots and milk, cooked with spikenard, cloves, cassia, ginger, and nutmeg. For those who want to take things up a notch, there is a similar dish, which adds dates (تَمْر, tamr) and ground walnuts. When the mixture has thickened, it is removed from the fire and left to settle. If you think that the resulting dish looks somehow familiar, you’d be right. Except for the absence of cardamom, it bears an uncanny resemblance to the classic Indian desert known as gajar (ka) halwa. Though appearing in an Arabic treatise, the dish was probably born in Persia. Either way, this may well be the oldest recorded recipe of gajar halwa.

Valentine’s Day rose syrup (شَراب الوَرْد, sharab al-ward)

A 13th-century Egyptian recipe for a sweet rose drink, made by boiling sugar syrup with rose petals, preferably fresh, but you can also use dried petals and soak them in water overnight. The result is a brightly coloured delicacy that is a perfect accompaniment for a special day!

The world’s oldest nougat recipe

Although the Arabs probably inherited nougat from the Persians, the oldest recorded recipes (six in total) are found in a 10th-century cookery book, where it is called nāṭif (ناطف). There are some recipes for this delicacy in other mediaeval Arabic cookery books, though it is conspicuous by its absence from those compiled in Egypt. In any case, making nougat was serious business, and required a number of dedicated utensils, including a round copper pot for boiling it, a wooden spatula for beating it, as well as a rolling pin and wooden board or marble slab for spreading it out. Even the design of the pot was carefully prescribed; it should have a rounded bottom and three legs to stop it from spinning around when beating and whitening the nougat on a wooden board. It is a bit tricky and labour-intensive to make, but the results are worth it! The recipe recreated here is that for a Harrani nougat, named after the city it allegedly came from (present-day Harran in Turkey). It requires about 1.7 kg of honey, as well as egg-whites, various spices and seeds (e.g. cassia, cloves, spikenard, hemp seeds), and a plethora of fruits and nuts (e.g. almonds, pistachios, dried cocounut). In addition to its cholesterol-enhancing qualities, it was also said to be hard to digest and to cause blockages. Then again, a good thing merits sacrifices! At least, that is what royalty must have thought, too, as the same book contains a nougat recipe made for the great caliph al-Ma’mun as a travel snack ( a bit like our trail mix or energy bar), with the author adding that “one can take it along wherever one goes and it lasts for as long as you like.” The delicacy spread throughout the Mediterranean but it is probably in Malta that it achieved the highest status as the emblematic festa food; as the Maltese saying goes: Festa bla qubbajd mhix festa (‘A feast without nougat cannot be called a feast)!

Latticed cake (مُشَبَّكة, mushabbaka)

A thirteenth-century Egyptian recipe which requires semolina flour, carlified butter, honey, rose water, and rose-water syrup. For the decoration, use crushed pistachios, hazelnuts, almonds and sugar.

Mediaeval Egyptian doughnuts (كاهِين, kahin)

Surprisingly light, these scrumptious doughnuts are made with egg-whites and starch, and slathered in rose-water syrup . The name is probably a corruption of kāhin or kahīn, meaning ‘soothsayer’ and ‘magician’, respectively. [Ibn Mubārak Shāh, fol. 20v.] They become even more irresistible when you sprinkle on some icing sugar.

Date balls ( هَيْس, hays)

An Egyptian recipe (13/4th century) for dainty date balls made with either bread or ka’k crumbs, date paste, a variety of nuts (almonds, walnuts, pistachios), and toasted sesame seeds. Sprinkle with caster sugar before serving.

No 50! Oxymel candy

Besides its use as a refreshing drink, oxymel can also be turned into this wonderful sweet, which was recommended for those with hot temperaments. The ingredients couldn’t be simpler: rose-water syrup (jullāb) and vinegar. [Ibn Mubārak Shāh, fol. 22r.-v.]

Apricot leather (قَمَر الدِّين, Qamar al-Din)

The present-day Qamar al-din refers to a drink made from apricot leather (usually added with rose water), rather than the paste itself. It is a very popular drink (often associated with Ramadan) all over the Middle East, especially in Syria (its original homeland) and Egypt. In the Middle Ages, it was also used in cooking, and is specifically mentioned in a 13th-century Levantine recipe. None of the medieval Arabic culinary treatises provided instructions on how to make it, but thankfully the famous blind Christian physician Dawud al-Antaki (d. 1599) did, in his medical handbook entitled ‘Memento for the wise and a collection of marvellous wonders’ (تذكرة أولي الألباب والجامع للعجب العجاب). It is very straightforward and not different from today’s methods, except in the absence of sugar. After macerating the apricots, they are beaten into a mash, placed on boards coated with sesame oil and left out in the sun. (in case you live in a country in short supply of sunlight, a dehydrator does the trick very nicely, too!) The result, so al-Antaki tells us, should be thin sheets. [al-Antaki, 1884, I, p. 307] In Iran, it is known as the children’s favourite lavashak (لواشک) and denotes fruit rolls, made with a variety of fruits.

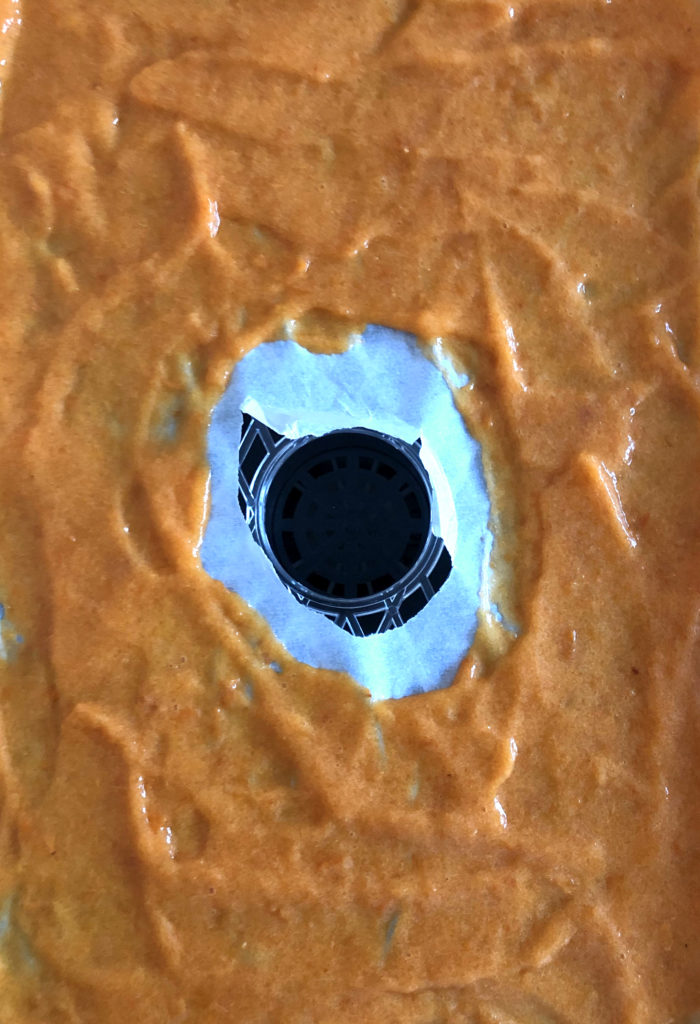

Drying the apricot paste

Dried sheets of apricot leather

Apricots stuffed with almonds

This 13th-century Egyptian recipe takes a bit of time to make, but it is well worth it. The apricots are macerated in a mixture of rose water syrup, saffron and musk. Other ingredients include wine vinegar, and the atrāf al-tīb spice mix. The almonds are blanched and coloured with saffron before stuffing them inside the apricots.

Layered date galettes

This 13th-century recipe was a speciality of the region around Constantine (Algeria), and was associated with the Kutamiyya Berber tribe. It is known in Arabic as al-murakkaba (المُرَكَّبة, ‘the compound one’) because it involves layers of flat loaves (or galettes) made with semolina dough and eggs, alternating with layers of date paste. After completing the stack with however much dough you have made, pour over honey and clarified butter (ghee). Dust with cinnamon before serving. [Andalusian, fol. 65.r.]