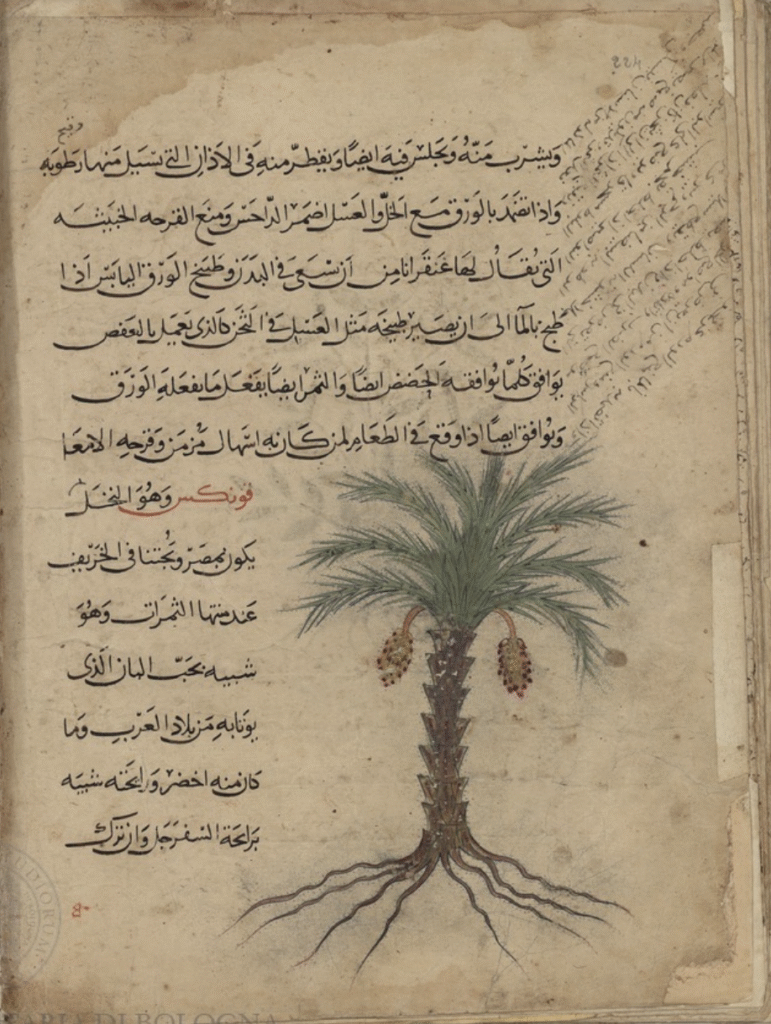

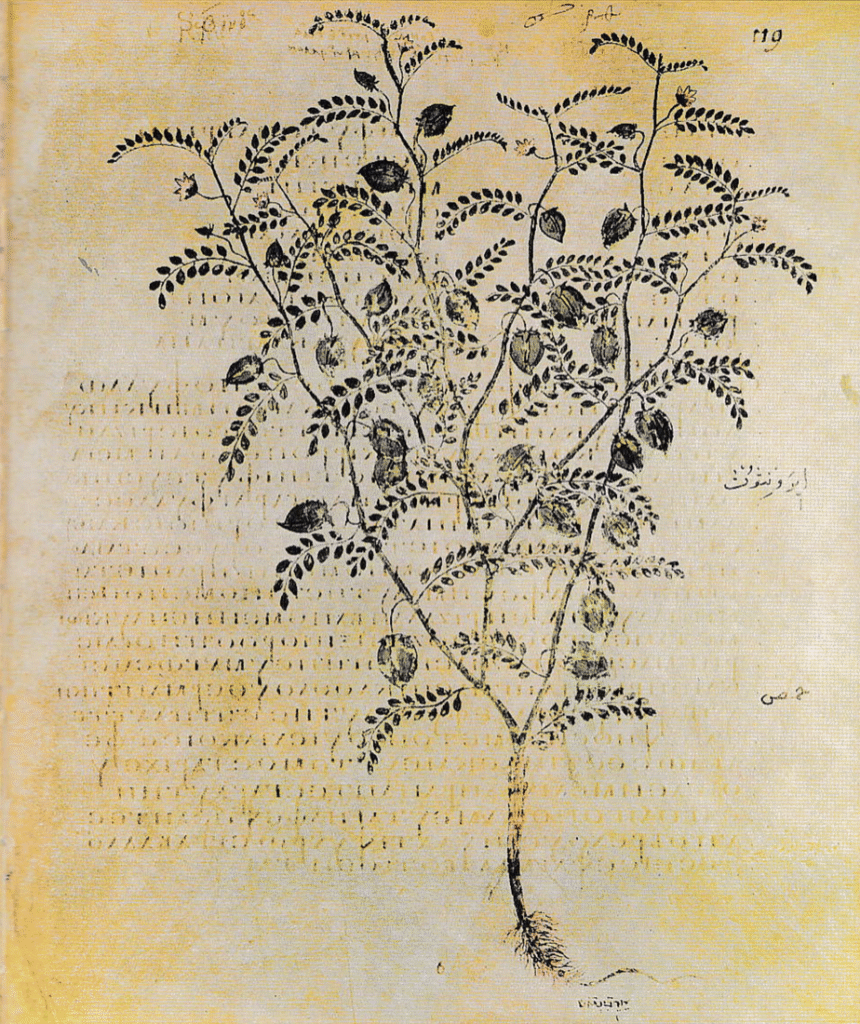

The fruit of the palm tree (Phoenix dactylifera L.), dates have played a crucial role in North Africa and the Near East; it was particularly abundant in Palestine and Phoenicia (the name actually comes from the Greek word for palm tree, foinix/φοίνιξ). Since time immemorial, dates were a staple food of desert dwellers, for whom it was a rich source of carbohydrates (due to the high sugar content) and protein, and was often eaten with milk. In addition, the pith (jummār) was – and still is – consumed, whereas the sap of the trunk, when fermented, became palm wine.

There is evidence that date palm was already cultivated in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, where it was a key component in the diet. Dates were the main ingredient in a famous Babylonian bread called mersu, which was commonly used in public worship and exorcism rituals and could also contain raisins, apples or figs, as well as — somewhat surprisingly to modern diners — garlic, cumin and coriander! In ancient Egypt, dates were a staple as well and there are numerous references to them eaten fresh, dried or made into breads, cake, or wine. The date palm is also a common motif in ancient Egyptian art, whether it be palmiform columns or in illustrations in reliefs and frescoes.

Although the tree grew in ancient Greece, it did not yield any fruit. The Romans, on the other hand, were very keen on dates, which they imported from Syria and, especially, Egypt, both of which make an appearance at Trimalchio’s dinner in Petronius’ Satyricon. The fruit is called for in over thirty recipes of Apicius’ cookery book.

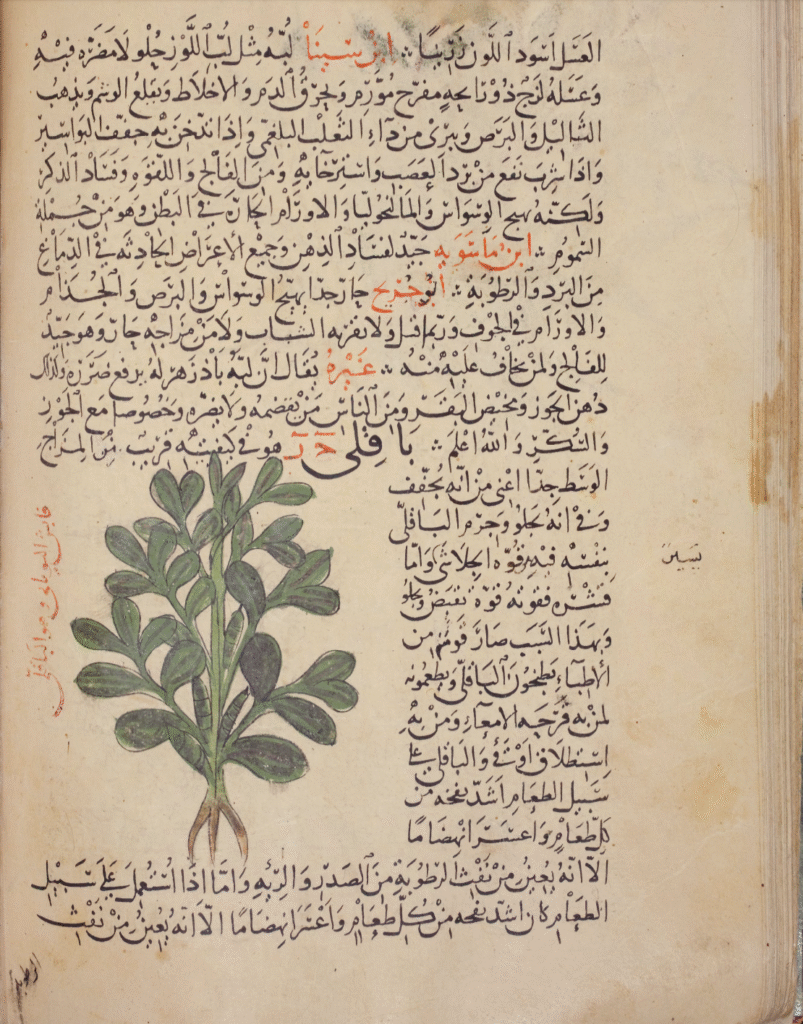

It is difficult to overstate the significance of dates – of which there are allegedly 300 varieties — in Muslim culture, as a divine beneficence to mankind, and is mentioned in this regard almost twenty times in the Qurʾān. The Prophet, himself, was said to be particularly fond of eating dates, as borne out by a number of hadiths: ‘The household of Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, never ate two meals in a day but that one of them consisted of dates’ (مَا أَكَلَ آلُ مُحَمَّدٍ صَلَّى اللهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ أَكْلَتَيْنِ فِي يَوْمٍ إِلَّا إِحْدَاهُمَا تَمْر); ‘A family which has no dates will be hungry’ (بَيْتٌ لاَ تَمْرَ فِيهِ جِيَاعٌ أَهْلُهُ). Dates are also associated with breaking the fast during Ramadan, whereas they are a traditional food to serve when welcoming guests.

The main successive stages in the growth of the fruit are known as: ṭal’ (طَلْع, when the date begins to take shape inside the spathe), khalāl (خلال, when they begin to colour), balaḥ (بلح, when they are still green and small), busr (بسر, yellow-red in colour and already sweet), ruṭab (رطب, fresh and ripe), and tamr (dried). According to the earliest Arabic lexicographer, al-Khalīl al-Farāhīdī (718 – 786), balaḥ were the equivalent of sour unripe grapes (wa-huwa ḥamlu l-nakhli mā dāma akhḍara ṣighāran ka-ḥiṣrim ’l-ʿinab). This was later quoted by the polymath Abū Hanĩfa al-Dīnawarī (9th c.), but attributed to an unnamed ‘learned person’.

In pre-Islamic Arabia, dates ruṭab and tamr were used in a variety of preparations, ranging from hays (a sweet pudding made with clarified butter) to dibs (a term going back to Persian where it meant ‘black’, and denoting date molasses made by pressing dates without cooking). From Abbasid times onwards, dates – both can be found in recipes for meat stews (tamriyya) and, of course, sweets. Then, as now, dates would often be stuffed with nuts (notably almonds).

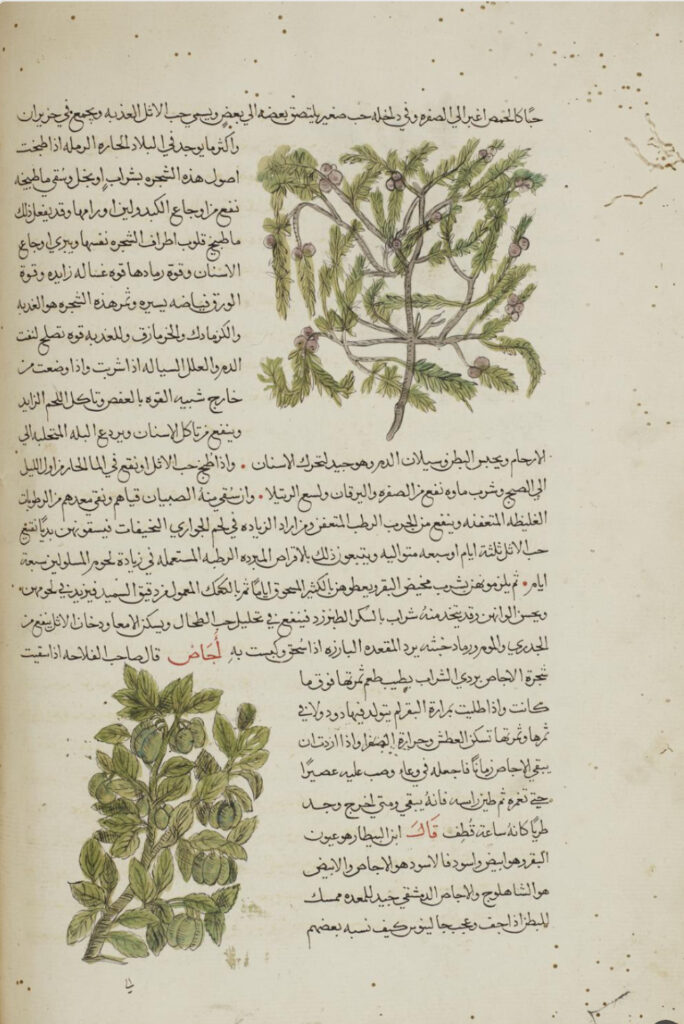

Medicinally, balaḥ were thought to be bad for the chest and lungs; whereas busr are useful for the mouth, gums and stomach, but are constipating. Ruṭab have a laxative effect (مُلَيِّن الطَبِيعة) — they are particularly harmful in cold countries where there they do not become sweet and do not ripen completely. All dried dates are difficult to digest, produce hot blood and cause obstruction and coarseness in the intestines. However, they are beneficial for people with cold temperaments and healthy intestines as it increases their fertility.

Any negative effects of dates can be counteracted with oxymel (sikanjabīn, سِكَنْجَبِين), sour pomegranate juice and cold foods (bawārid, بَوارِد). Physicians held that the best foods to eat with dates are almonds and poppy seeds.