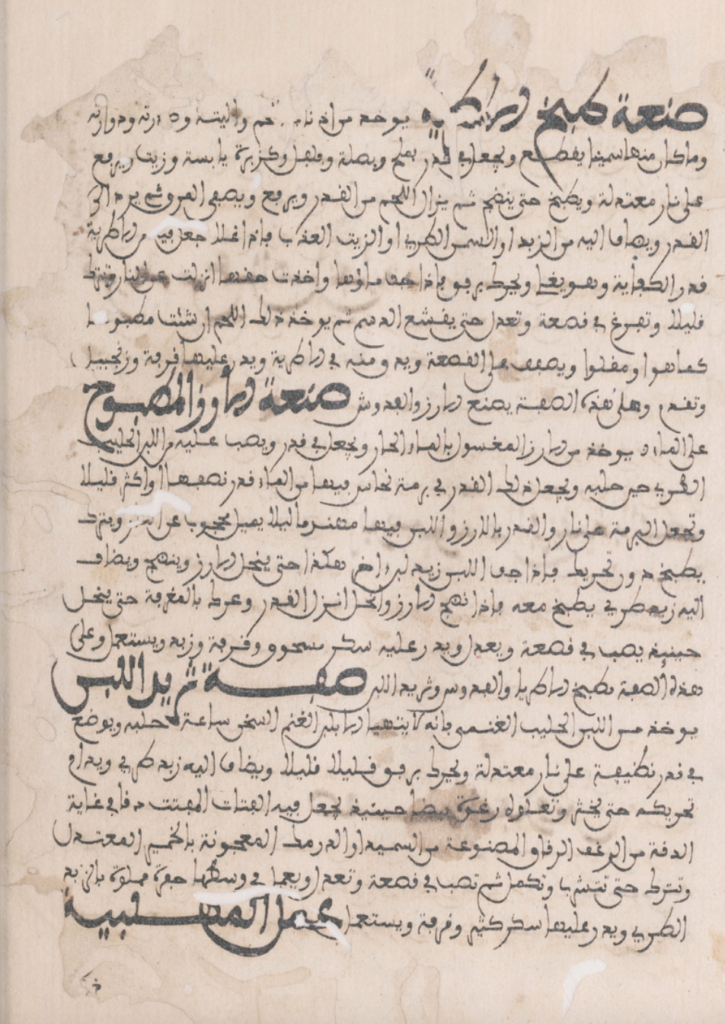

There are a number of khabis (خبيص) recipes in the medieval culinary tradition and often vary considerably in terms of ingredients and method from their present-day namesake, which is particularly associated with the Arabian Gulf. This khabis recipe from The Exile’s Cookbook is quite close to the modern sweet, as well as to dishes from other parts of the Arabic-speaking world, such as the Algerian tamina (طمينة). It is very simple to make and requires cooking honey, water, saffron, cinnamon pepper and spikenard before adding semolina. Then, it’s simply a question of stirring until you obtin the required consistency ‘of a thick pottage’. Before serving,olive oil is added to the pot for that extra bit of lubrication! Note that the khabis should be eaten cold. An important difference between this historic version and the modern descendants is that the latter generally call for toasted semolina.