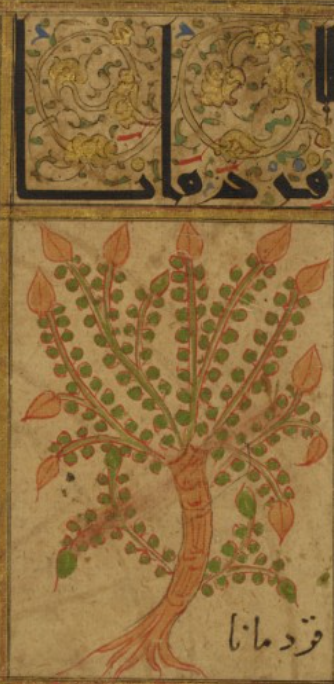

This is the ancestor of the modern North African delicacy, known as sfenj (سفنج) in Morocco and Algeria, bambalunī (بمبلوني < Italian bombolone) in Tunisia, and sfinz (سفنز) in Libya. Both the Arabic word isfanj (إسفنج) and the English ‘sponge’ go back to the Greek σπογγιά, albeit via the Latin spongia (spongea).

Interestingly enough, in this recipe from The Exile’s Cookbook is, in fact, very similar to another Arab sweet variously known as ‘awwāma (عوامة, ‘floater’), luqmat al-Qāḍī (لقمة القاضي, ‘The Judge’s morsel’), zalābiyya (زلابية) or luqayma (لقيمة, ‘little morsel’), depending on the region.

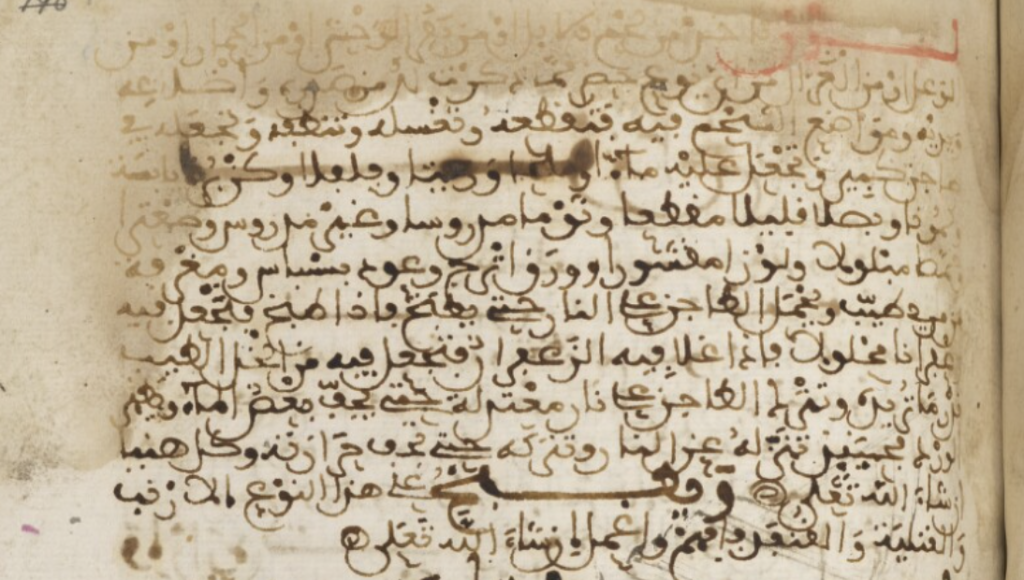

This particular isfanj is made with semolina, water, salt and yeast being kneaded into a light dough. After proofing, the idea is to take some dough into your hand and clench your fist, as a result of which some of the dough is forced out from between your thumb and index finger. It is this piece that protrudes that will be deep-fried in olive oil.

They were made in two sizes — small and large, known respectively as mughaddar (مغدّر) and aqṣād (أقصاد). Once the isfanj have turned golden, remove them from the pan and, after draining off the oil, and serve. Note that before frying up the first batch, the author recommends using one shaped like a modern doughnut shape to test whether the dough has been sufficiently proofed. They are particularly nice when dunked in honey!