The broad (or fava) bean (Vicia faba) has been called the most important legume in human history and for millennia was the most important bean staple in Europe, Western Asia and northern Africa, until it was supplanted by the haricot bean, an import from the Americas.

In ancient Egypt, so the historian Herodotus tells us, beans were avoided by Egyptian priests. In ancient Greece, they were eaten raw, boiled and roasted, and often accompanied drinks, very much like our present-day tapas. The Greek philosopher Pythagoras forbade them for his disciples allegedly because the beans were generated by the same putrefactive material that generates human beings, or because he thought that the souls of the dead dwell in them.

In Arabic, broad beans are known as bāqillā (باقلى), fūl (فول) and, more uncommonly, jirjir (جرجر), from the Persian girgir (گرگر). They do not appear very often in the medieval culinary literature as this reflects an elite cuisine, and broad beans were primarily part of the common people’s diet. When they are mentioned, it is in stews (known as fūliyya/فولية), boiled in broths, gruels and porridges, or in tabahija (طباهجة) recipes, a dish made with fried slices of meat. The highest number of broad bean recipes is found in 13th-century cookery books from al-Andalus, which contain the oldest recipe for baysār (بيسار), a porridge made with dried ground broad beans, as well as meat. This is the ancestor of the modern Moroccan and Egyptian favourite, biṣāra (بصارة), which is usually known as bissara or bessara in English. According to the tenth-century traveller al-Muqaddasī, the dish was already an Egyptian speciality, though he also encountered it in Greater Syria. It is very likely it originated in Egypt since the name can be traced back to the Coptic pesouro. In Morocco, it is made with garlic, olive oil and spices, and is often eaten for breakfast.

Scholars usually identified two varieties: Egyptian, and Nabataean (Nabaṭī). Ibn Sīnā also referred to an Indian variety and only applied jirjir to the Nabataean one. Medically, broad beans were considered slow to digest and highly flatulent (according to some, no other grain equals them in this regard), though this could be counteracted with lengthy cooking or roasting. The Nabataean variety was thought to be particularly constipating, as were the husks, and for this reason unpeeled broad beans cooked in vinegar were prescribed against diarrhoea and vomiting. Other negative effects include nightmares and headaches. On the plus side, broad beans were said to be useful against ulcers (if cooked with vinegar and water,), freckles and coughs (when and cooked with almond oil and sugar and drunk lukewarm).

Broad-bean flour was also used to make bread, which, however, was also frowned upon due to its flatulent properties; one should eat it with a lot of salt and accompanied by a murrī dip, and avoid drinking cold water after it.

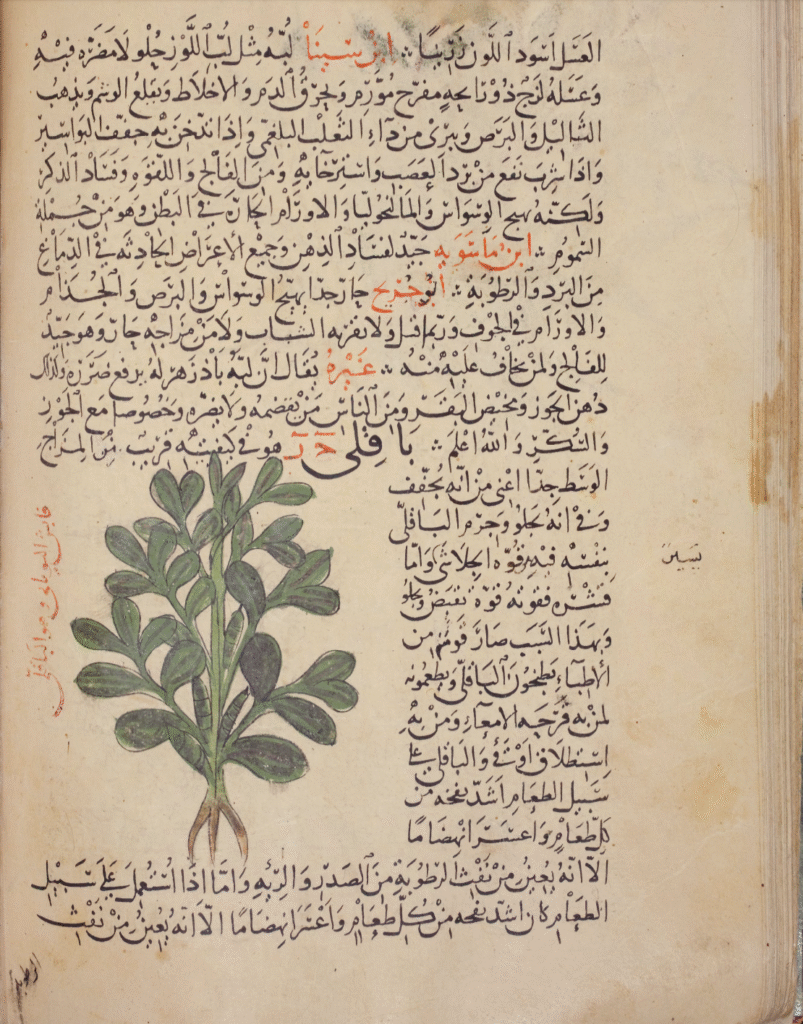

broad beans in al-Ghafiqi’s herbal (12th century), where they are described as “fābish al-yūnānī (‘Greek fava’), which is bāqillā”.