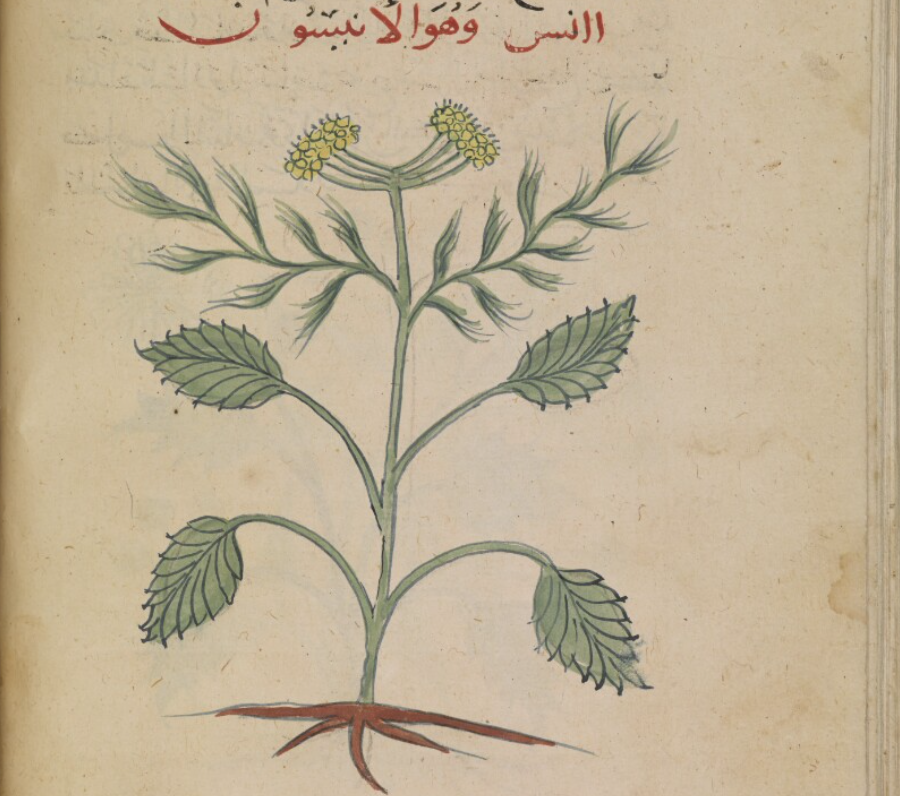

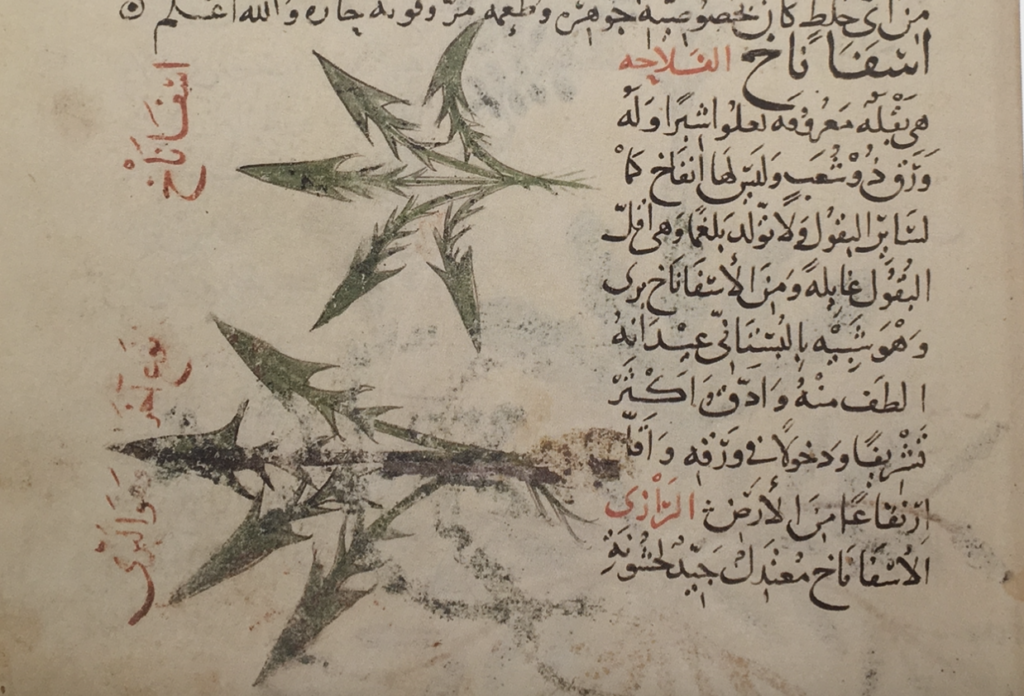

Anise (Pimpinella anisum) is a plant that has been grown for its aromatc seeds since Greek Antiquity and originated from the Eastern Mediterranean. According to Dioscorides, Cretan anise was the best, followed by the Egyptian variety. The Greeks already used it in a medicinal decoction called anisaton, which is the ancestor to the present-day ouzo and raki. Anise seeds were also bound into a sachet which would be put in wine for flavour and its medicinal effects, as a digestive and aphrodisiac. In Roman cuisine, it was used as an aromatic, especially in sauces, and Apicius listed it among the spices a cook should have to hand.

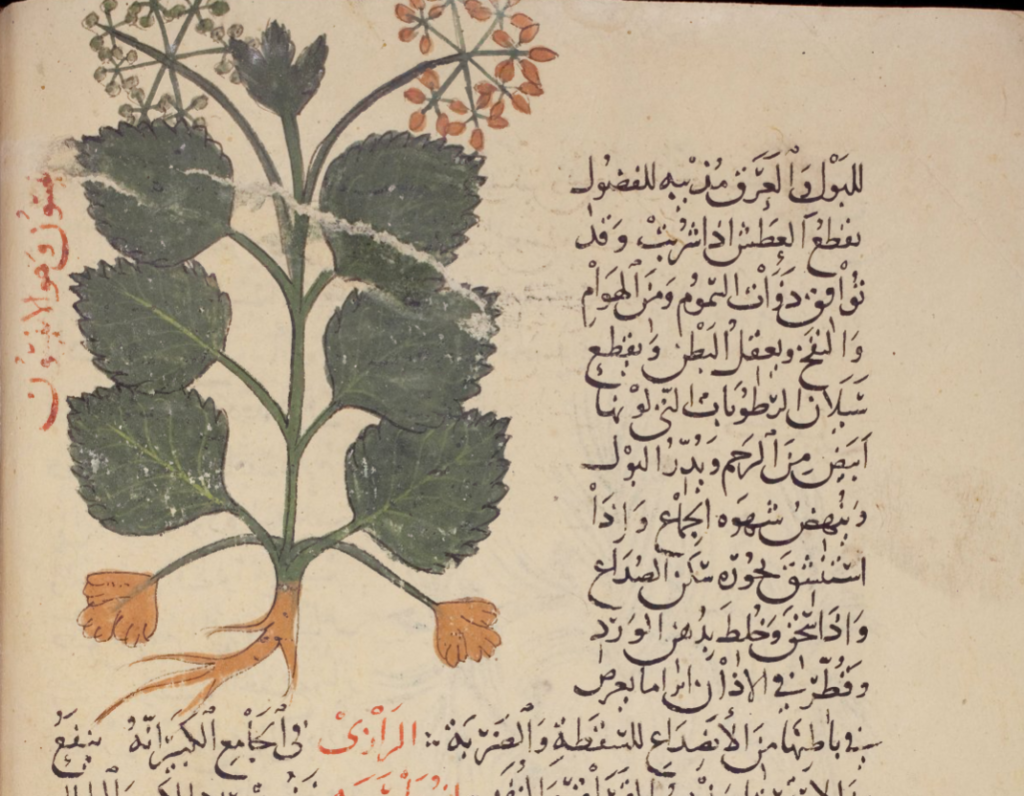

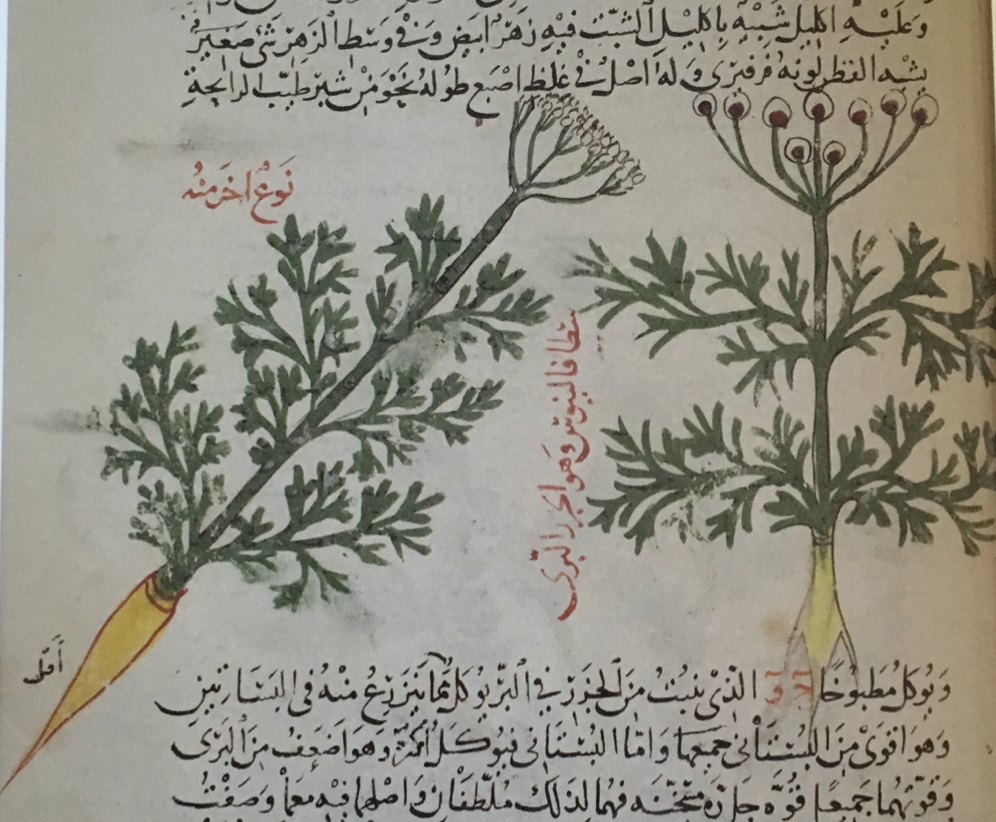

In Arabic, anise is usualy known as anīsūn (أنيسون) but in the literature other names include rāziyānaj Rūmī (رازيانج رومي; ‘Roman fennel’), kammūn abyaḍ ḥulw (‘sweet white cumin’), and — especially in al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) — al-ḥabba al-ḥulwa (الحبّة الحلوة; ‘the sweet grain’). It was not used very often in medieval Arab cooking; it is found in recipes for baked goods (ka’k, bread) and condiments such as dips and murrī.

Medically, anise was thought to be useful against flatulence and liver blockages, as well as being a diurretic and emmenagogue. Fumigating the seeds and sniffing the vapours was said to be good for headaches. It is even effective as an antidote to poisons, but, according to Ishaq Ibn Hunayn, it is harmful to the bowels.