The plum (Prunus domestica) is part of a family including apricots, peaches and cherries. The origins of the fruit have been lost in the mists of time, but it is likely that its cradle is to be bound in the southern and eastern Mediterranean. The earliest references to the use of plums in culinary recipes are to be found in Apicius’ cookery book, where Damascus plums (so named because they were imported from Syria), are an ingredient some sauces served with meat (crane, duck, chicken, lamb).

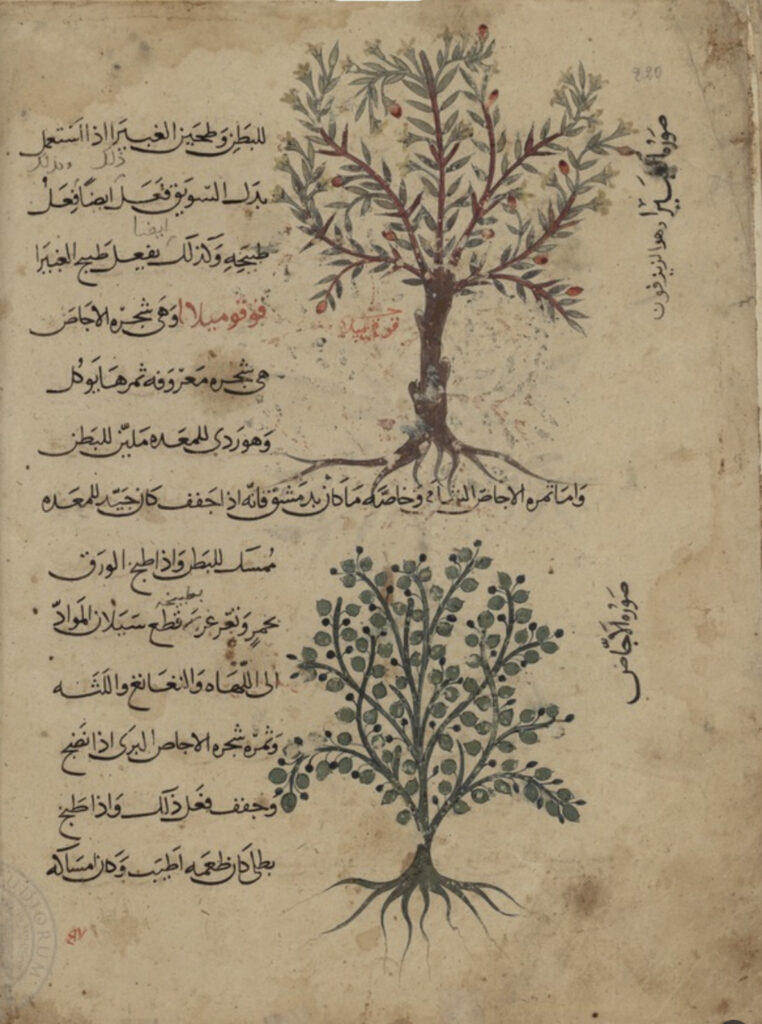

In Arabic the plum is known as ijjāṣ (إجّاص) but in some dialects (e.g. Syria) this denotes pears (كمّثرى, kummathrā), with plums being called khawkh (خوخ), which is the usual word for peaches. In Andalusian and Maghrebi Arabic plums were known ʿayn (plural: عيون, ʿuyūn) al-baqar (عين البقر, ‘cow’s eyes’), sometimes abbreviated to ʿabqar; according to the 13th-century botanist Abū ’l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī, they were ‘so called because the fruit resembles in size, brightness, and moisture the pupils of cows’.

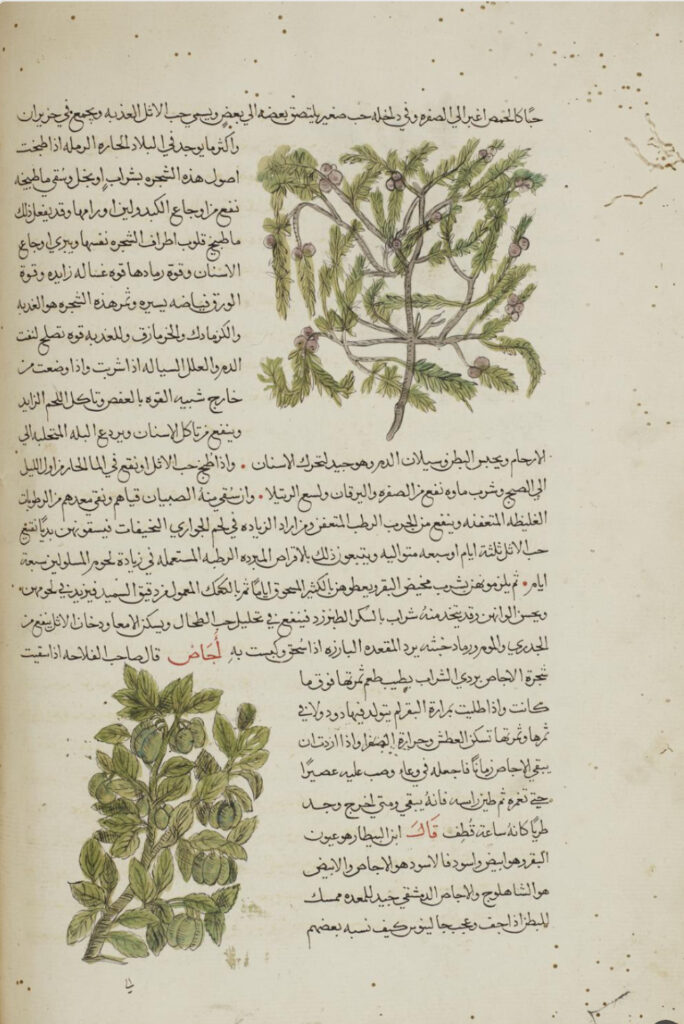

The same scholar distinguished a number of different types, including yellow (أصفر/aṣfar, also known as مشمشي/mishmishī, ‘apricot-like’), white (أبيض/abyaḍ; also شاهلوج/shāhlūj or شاهلوك /shāhlūk), red (أحمر/aḥmar), rosy (/مورّد/muwarrad) and pitch-black (أسوج حالك/aswad ḥālik). Other scholars referred to green, red, black and white plums, whereas the best fruits were said to be those from Qumis (Iran), Halwan (Egypt), and the Armenian variety.

In the medieval Arabic culinary literature, plums are conspicuous by their absence from Syrian and Egyptian cookery books, and were used only sparingly in Abbasid sources, where they are called for in a chicken stew, and as the key ingredient in a few syrups. There are also a few recipes for stews in 13th-century Andalusi treatises, with the author of ‘The Exile’s Cookbook’ stating that they were imported from ‘the land of the Christians’ (northern Spain). They mainly occur in sweet-and-sour stews, such as one with veal, or with lamb. The latter was known as muruziyya (مروزية), which, according to another cookery book, was said to be the food of Tunisians and Egyptians. In present-day Morocco, murūziyya, refers to lamb tajine with raisins and almonds, but sometimes also includes plums.

In the medical literature, there was a consensus that plums had limited nutritive value, but were useful loosening the bowels and cooling the body. Large, sweet plums were thought to be more effective as laxatives and less cooling, while sour kinds are less laxative but more cooling. The fruit is particularly effective when its juice is strained and mixed with sugar or honey. However, it weakens the stomach, which can be corrected with julanjubīn (جلنجبين), a rose-petal conserve.

The physician al-Isrāʾīlī (9th-10th c.) held that the shāhluj was slow to digest, harmful to the stomach, and only slightly laxative, and should be eaten only when very ripe and large. The black, ripe, sweet plums moisten and relax the stomach and loosen the bowels. He, and many others, condemned green plums both as food and medicine as they are unpalatable and indigestible. Al-Isrāilī concluded that the best plums were those that are fleshy with thin skins, slightly bitter, and gently astringent. They should be eaten about an hour before meals, on an empty stomach.