A dish allegedly created by the hedonistic prince Ibrahim Ibn al–Mahdi (779-839), the half-brother of the famous Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, who makes numerous appearances in the Arabian Nights. Ibn al-Mahdi was known as a singer, poet, and gastronome, and this recipe is probably from his cookery book (كتاب الطبيخ, kitab al-tabikh), which has unfortunately been lost. The dish is essentially a grilled chicken rubbed with salt, thyme, and olive oil, and then basted with the juice of both sweet and sour pomegranates, mixed with murrī. It is served with a rich gravy made with the chicken juices and crushed walnuts. According to the author of the 10th-century treatise who has preserved the recipe, it is “delicious, flavoursome, wondrous, and often used (لذيذة، طيّبة، عجيبة، مستعملة).” Deservedly high praise, indeed.

Quince jelly (مَعْجُون السَّفَرْجَل, ma’jun al-safarjal)

A delicious quince preserve recipe from 13th-century Andalusia. The Arabic word ma’jūn is related to a verb meaning ‘to knead’, and denotes a paste, usually for medicinal use, though the result is often so tasty that one does not need to be sick to enjoy it! The preparation could not be simpler and requires about a pound of quince and sugar. According to the author, the jelly can be used to remove bitterness in the mouth, arouse the appetite, but also prevents bad vapours (بخارات, bukhārāt) from rising from the stomach to the brain. You can’t say fairer than that, can you!

Sweet carrot pudding (خَبِيص الجَزَر, khabis al-jazar)

A delicious 10th-century Iraqi dish of carrots and milk, cooked with spikenard, cloves, cassia, ginger, and nutmeg. For those who want to take things up a notch, there is a similar dish, which adds dates (تَمْر, tamr) and ground walnuts. When the mixture has thickened, it is removed from the fire and left to settle. If you think that the resulting dish looks somehow familiar, you’d be right. Except for the absence of cardamom, it bears an uncanny resemblance to the classic Indian desert known as gajar (ka) halwa. Though appearing in an Arabic treatise, the dish was probably born in Persia. Either way, this may well be the oldest recorded recipe of gajar halwa.

Andalusian Fish pie

The dish was known as al-Jamalī (الجَمَلِي) and is found only in 13th-century Andalusian and North African treatises. The recipe recreated here is taken from a Tunisian manual, and requires fish to be left overnight covered in salt. On the day of cooking, it is washed and dried, before layering into a tajine (shallow earthenware stewing pan). The other ingredients include vinegar, murrī, pepper, saffron, ginger, cumin, mastic, celery seeds, citron leaves, laurel leaves, fennel, thyme, garlic and a lot of olive oil. Place in the oven until the liquid has dried and the top has turned golden brown. It goes wonderfully well with couscous or with some fresh flatbread!

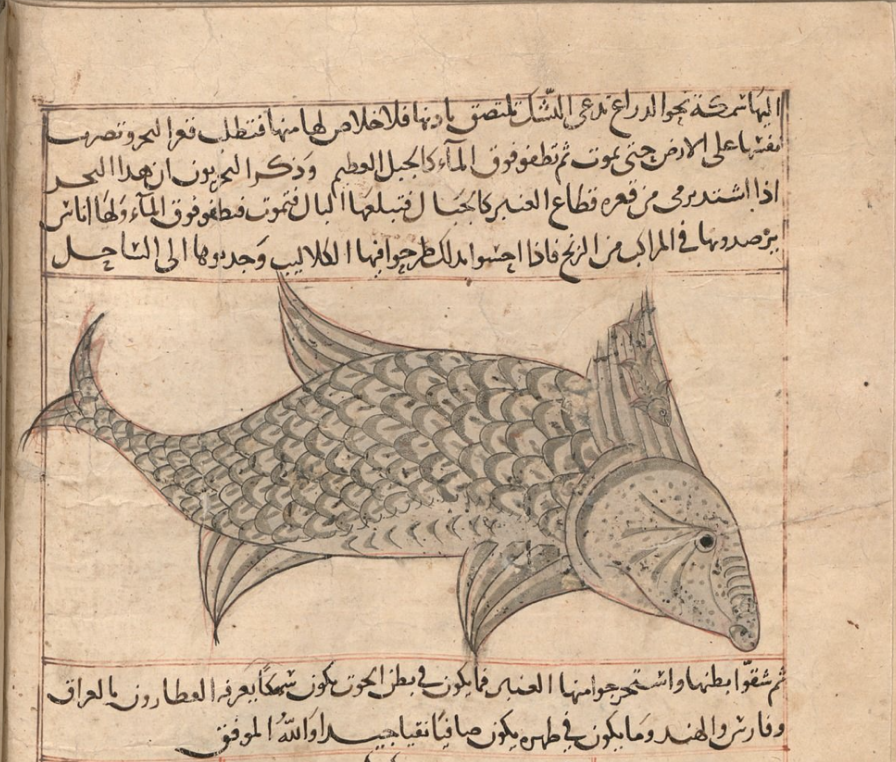

Spotlight on: Ambergris (عَنْبَر, ‘anbar)

Also known as grey amber (Ambra grisea), it is a substance secreted from the sperm whale’s gall bladder. The grey variety (which with age turns black) should be distinguished from yellow amber, which is fossilized tree resin. Both have been used in perfumes and medicines, but only yellow amber was (and still is) prized as a gemstone. The ancient Greeks knew it as elektron, which gave the word ‘electricity’, initially meaning static electricity because of amber’s capacity to attract other materials after friction. One of the earliest references to the importation of ambergris can be found in the 9th-century travel book Akhbār al-Sīn wa ‘l-Hind (أخبار الصين والهند, ‘News from China and India ’), which mentions the inhabitants of Lanjabālūs (Nicobar Islands) in the Sea of Harkand (Bay of Bengal) trading ambergris for iron with Arab merchants.

Ibn Sina (Avicenna) thought that the source of ambergris is a spring (عين, ‘ayn) in the sea, and dismissed the claims that it is the excretion of an animal. He considered grey amber the best, followed by blue and yellow, whereas the black variety is of the worst quality, as it’s obtained from the stomach of fish that have ingested ambergris and is then adulterated with other substances like gypsum or wax. Medicinally, ambergris is beneficial for the brain, senses, and heart.

Ibn al-Bayṭār called ambergris ‘the king of scents’, and recommended it (by mouth, in a cream, or as a fumigant) as a remedy for flatulence, migraines, and to strengthen the joints and stomach. He added that ambergris immediately increases the intoxicating effect of wine.

The sixteenth-century Portuguese physician Garcia da Orta, who wrote extensively on the spices of the East, still subscribed to Avicenna’s view that ambergris came from a fountain gushing forth from the bottom of the sea, adding that most of it was cast on the Comoro Islands, Mozambique, and the Maldives. He claimed that he had seen pieces as big as a man, while in Chinese medicine it was thought to be very beneficial for women’s ailments, the heart, the brain, and the stomach.

Ambergris was used as an ingredient in medicines, incense tablets, and perfumes. In cooking, it appears as a fumigant to scent a bowl or as a flavouring in dishes.

Valentine’s Day rose syrup (شَراب الوَرْد, sharab al-ward)

A 13th-century Egyptian recipe for a sweet rose drink, made by boiling sugar syrup with rose petals, preferably fresh, but you can also use dried petals and soak them in water overnight. The result is a brightly coloured delicacy that is a perfect accompaniment for a special day!

Spotlight on: Mastic (مَصْطَكى)

The Arabic word maṣṭakā (or maṣṭikā) is a borrowing from the Greek mastíkē (μαστίχη), which is derived from a verb meaning ‘to chew’. Possibly the world’s oldest chewing gum, it is the aromatic dried resin of the pistachio tree (Pistacia lentiscus), and came in a number of varieties: yellow/white (ʿilk al-Rūm, ‘Greek gum’) and black (terebinth, mostly Egyptian or Iraqi in origin). In classical Antiquity, as now, mastic was associated with the island of Chios as the only place where it could be obtained. In mediaeval Arab cooking, mastic was used in a variety of dishes, including fruit stews and sweets. The other main area of application was in perfumes. Islamic physicians believed it strengthens the stomach and liver, curbs appetite, and improves the appearance of the skin. Just like in ancient Greece, it was used as breath-sweetener and teeth cleanser.

Mediaeval Egyptian ravioli (شيشبرك, shishbarak)

This recipe, which is found in 13th- and 15th-century Egyptian cookery books, is the ancestor to the modern Lebanese favourite. Its name betrays a Turkish origin and it is likely that the dish was imported by Turkic tribes from the Central Asian steppes. The oldest recorded ravioli-type dish is the Chinese laowan from the third century CE. The Egyptian recipe requires dough to be made like tuṭmāj, from which round shapes are cut. After adding the stuffing (meat, spikenard, saffron, onion, mint), fold like ravioli and then boil in water. They are served with either yoghurt or macerated pomegranate seeds extract. It’s a good idea to make a good-sized batch so you have enough to freeze for future lunches!

Oven-roasted lamb kebabs

This recipe from 10th-century Baghdad is both flavoursome and easy to make. Cut tender lamb into slices ((شَرائح, sharā’iḥ) and marinate in fresh coriander (cilantro) juice, mixed with asafoetida. Coat the kebabs with olive oil before skewering, and then cook. Serve with rice and a wonderfully delicate dip made with red wine vinegar, murrī (use soy sauce), asafoetida and caraway seeds.

Spotlight on: Mustard (خَرْدَل, khardal)

Originally from Aramaic, the word refers to both white and black mustard (seeds). In cooking, the seeds – both whole and ground – are often required, with the black variety being used more often than the white/yellow. It is used to great effect, for instance, in the mustard chicken attributed to the Abbasid caliph al-Wathiq bi-‘llah. Mustard also appears in condiments, including a dip with raisins, known as sināb (صناب). The 13th-century anonymous Andalusian treatise instructed washing old mustard seeds with hot water before using them. Conversely, fresh mustard seeds do not need to be washed since they are tart without being bitter. The word also occurs twice in the Qur’ān (21:47; 31:16), where it is mentioned that even deeds weighing one mustard seed will be taken into account on the scales of justice. In medicine, cultivated mustard was preferred to the wild variety; it was considered useful against inflammations, tumours, scabies, and sciatica. It was also thought to increase intelligence (if taken on an empty stomach) as well as lust.