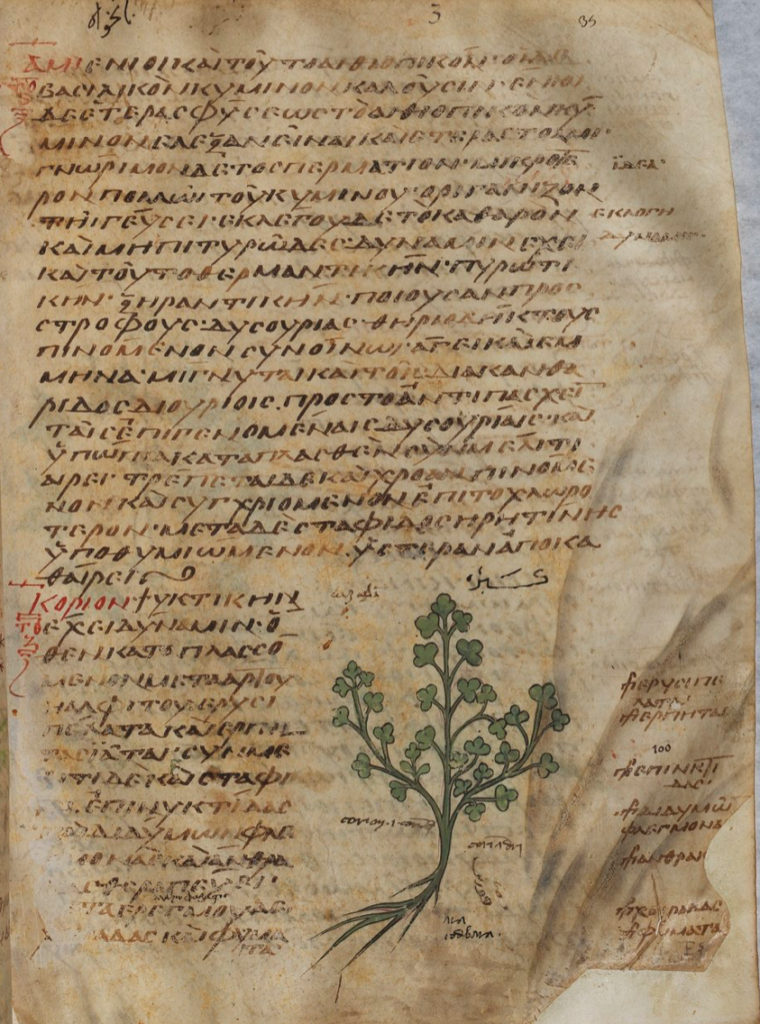

The English word actually refers to two varieties of seeds. The first is the so-called ‘common’ (also green, or lesser) cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum), known in Arabic as hāl (هال) or hayl/hīl (هيل). The spice is native to India’s Malabar coast and Indonesia, and though there is evidence that it was already known to Greek authors, it was very rarely used, and only in medicines. The second variety is bigger and is known as ‘black cardamom’ (Amomum subulatum), called qāqulla (قاقلّة) in Arabic.

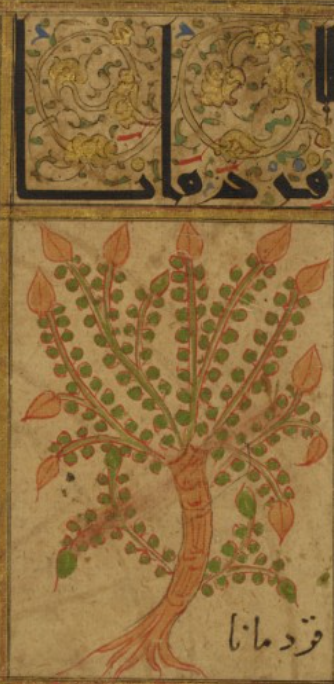

The terminology presents an interesting mix, with qāqulla going back to the Akkadian qāqullu, whereas hāl/hīl are borrowings from Persian derived from Sanskrit. Persia is also the origin of other names for common cardamom including the term بوا (bū, ‘odour’) — often rendered as buwwā, despite the final letter being silent –, such as khīr bū (خير بوا) and hayl bū (هيل بوا). Finally, qardamānā (قردماما) is a borrowing from Greek (kardamomon, καρδάμωμον).

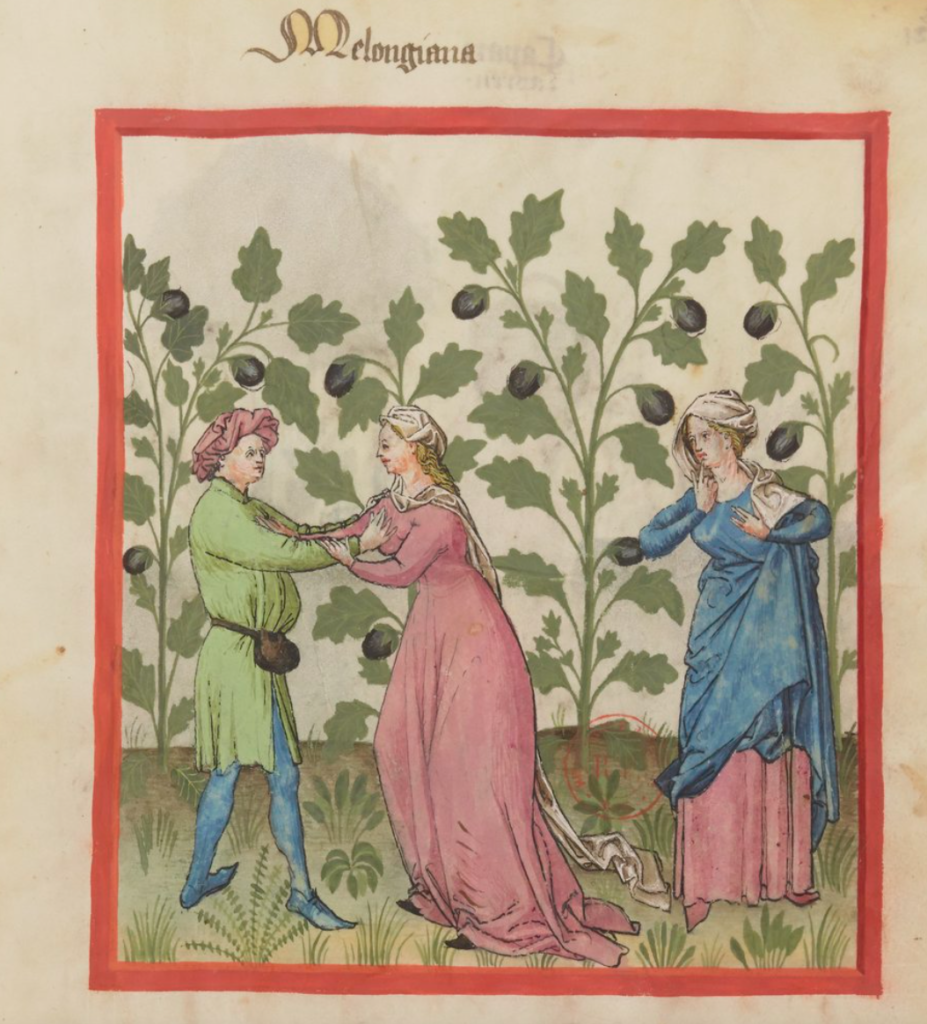

In medieval cookery books from the Near East, green and black cardamom are used in food only in an Abbasid treatise from the 10th century, in a medicinal drink (mayba). In other culinary sources, cardamom appears only in perfumes or hand-washing powders. Interestingly enough, in al-Andalus and the Maghrib, cardamom is used in a few recipes, such as a chicken garlic stew (ثومية, thūmiyya), a jūdhāba (جوذابة), and even some fish dishes.

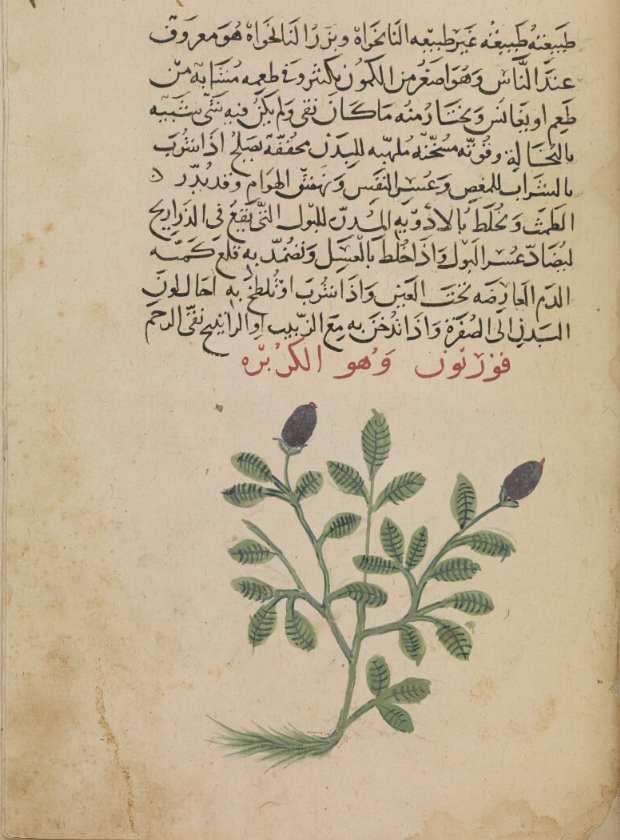

Medicinally, green cardamom was considered useful for the stomach and liver, and as an anti-emetic, whereas black cardamom was said to be a remedy for nausea and vomiting, while purifying the stomach and bowels. When drunk weekly with oxymel, it is good for epilepsy.

Today, green and black cardamom are mostly associated with Indian cuisine in both savoury and sweet dishes, as well as drinks (e.g. tea). The green variety is considered the best, and is also much more expensive. In the Middle East, green cardamom is an ingredient in in sweet dishes and, especially, as a coffee flavouring.

.