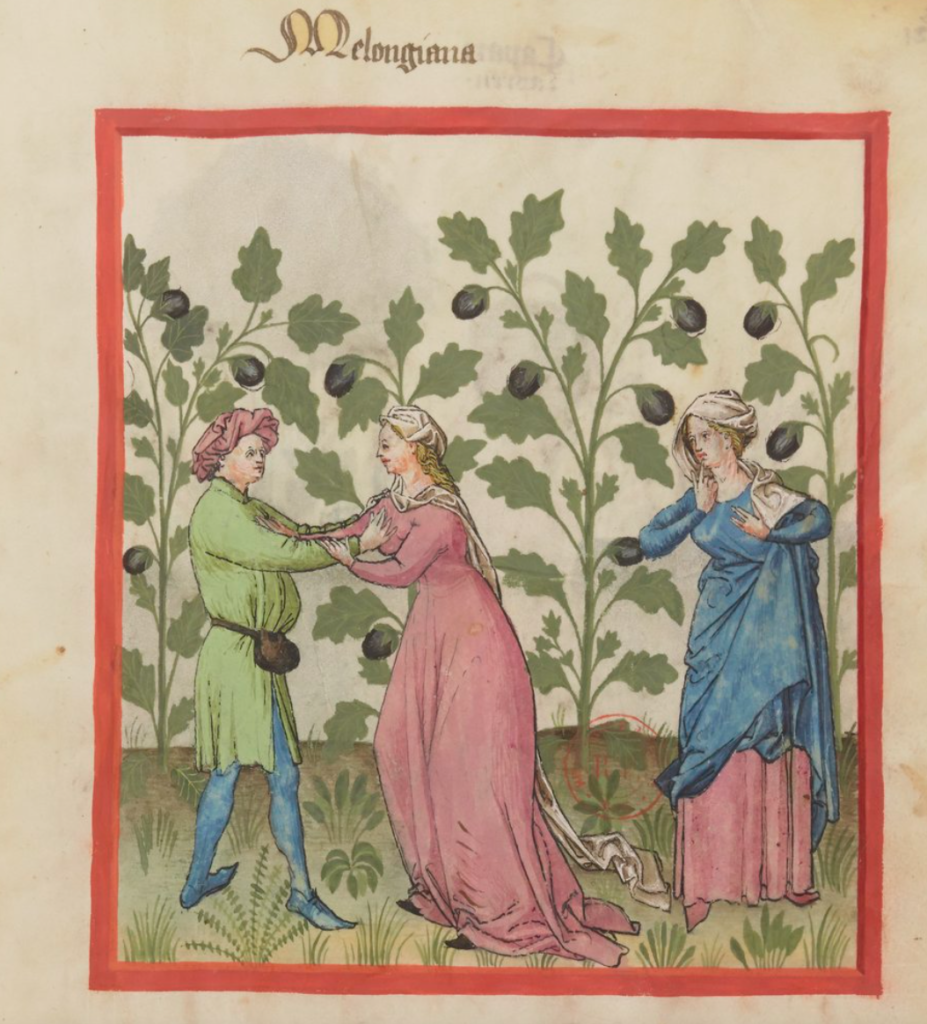

The ancestor of the modern aubergine (Solanum melongena) is a wild variety (Solanum incanum) from Africa, but became domesticated around the first century BCE in Asia (probably first in India and then China) before spreading towards the Mediterranean in the seventh century, reaching Spain by the 9th century. It was unknown in Greek or Roman Antiquity. The Arabs were introduced to it by the Persians, though it cannot be excluded that the aubergine reached Arabia directly from India in pre-Islamic times. The Arabic word is a Persian borrowing of Sanskrit origin (vangana), but it was known by a number of other names as well, such as the mysterious ‘snake warts’ (ثآليل الحيات, ta’ālīl al-hayyāt ) in the Maghrib.

In what is considered the earliest Arabic cookery book (10th c.), only nine (out of over 600) dishes call for aubergine, but its popularity clearly grew as time went on since only a few centuries later another Abbasid treatise used it in about ten per cent of the dishes. It was used primarily in stews, fried or stuffed. It was recommended to boil it in salt before cooking to eliminate the bitterness and expel its black juice. Its popularity grew even more in the Ottoman Empire, but in the Christian West, the aubergine came to be considered a ‘Jewish’ vegetable and was thus excluded from the diet of the devout Christian.

Despite its widespread consumption, physicians endowed it with many harmful properties, including causing black bile, obstructions, tumours, haemorrhoids, headaches, and even leprosy. It was thought to be noxious — even lethal — when eaten raw, though Ibn Buṭlān (11th c.) particularly warned against grilling it. According to the 10th-century Iraqi agronomer Ibn Waḥshiyya, aubergine should be eaten fried in oils and fats, with fatty meat. Its negative effects can be counteracted by cooking it with vinegar (though this causes constipation) and caraway. The Andalusian physician Ibn Khalṣūn (13thc.) , for his part, recommended the small white variety, eaten with fatty poultry or lamb.