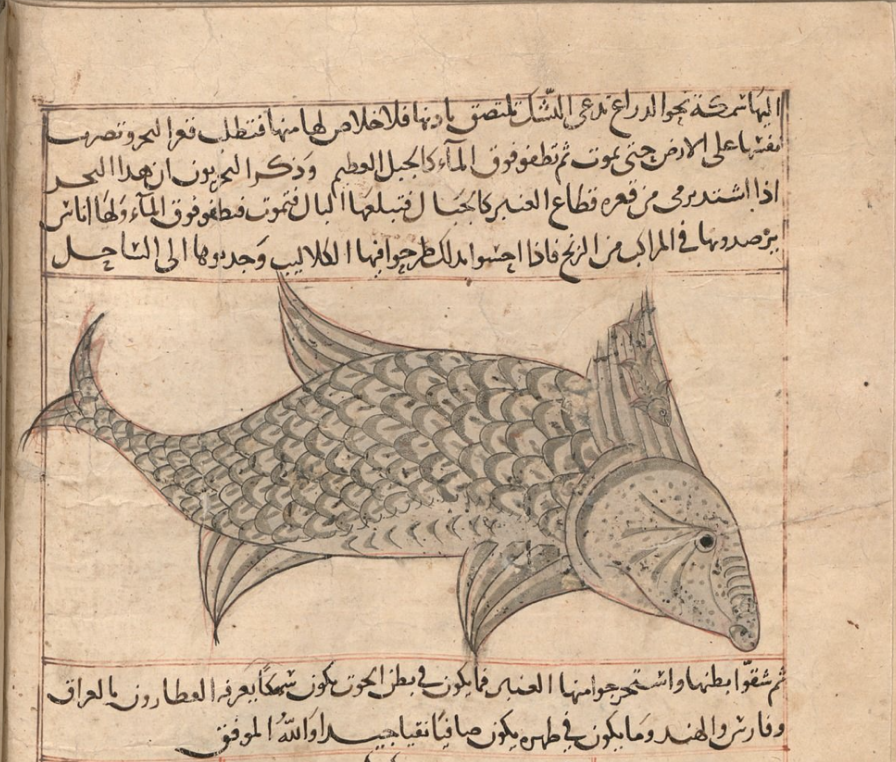

Also known as grey amber (Ambra grisea), it is a substance secreted from the sperm whale’s gall bladder. The grey variety (which with age turns black) should be distinguished from yellow amber, which is fossilized tree resin. Both have been used in perfumes and medicines, but only yellow amber was (and still is) prized as a gemstone. The ancient Greeks knew it as elektron, which gave the word ‘electricity’, initially meaning static electricity because of amber’s capacity to attract other materials after friction. One of the earliest references to the importation of ambergris can be found in the 9th-century travel book Akhbār al-Sīn wa ‘l-Hind (أخبار الصين والهند, ‘News from China and India ’), which mentions the inhabitants of Lanjabālūs (Nicobar Islands) in the Sea of Harkand (Bay of Bengal) trading ambergris for iron with Arab merchants.

Ibn Sina (Avicenna) thought that the source of ambergris is a spring (عين, ‘ayn) in the sea, and dismissed the claims that it is the excretion of an animal. He considered grey amber the best, followed by blue and yellow, whereas the black variety is of the worst quality, as it’s obtained from the stomach of fish that have ingested ambergris and is then adulterated with other substances like gypsum or wax. Medicinally, ambergris is beneficial for the brain, senses, and heart.

Ibn al-Bayṭār called ambergris ‘the king of scents’, and recommended it (by mouth, in a cream, or as a fumigant) as a remedy for flatulence, migraines, and to strengthen the joints and stomach. He added that ambergris immediately increases the intoxicating effect of wine.

The sixteenth-century Portuguese physician Garcia da Orta, who wrote extensively on the spices of the East, still subscribed to Avicenna’s view that ambergris came from a fountain gushing forth from the bottom of the sea, adding that most of it was cast on the Comoro Islands, Mozambique, and the Maldives. He claimed that he had seen pieces as big as a man, while in Chinese medicine it was thought to be very beneficial for women’s ailments, the heart, the brain, and the stomach.

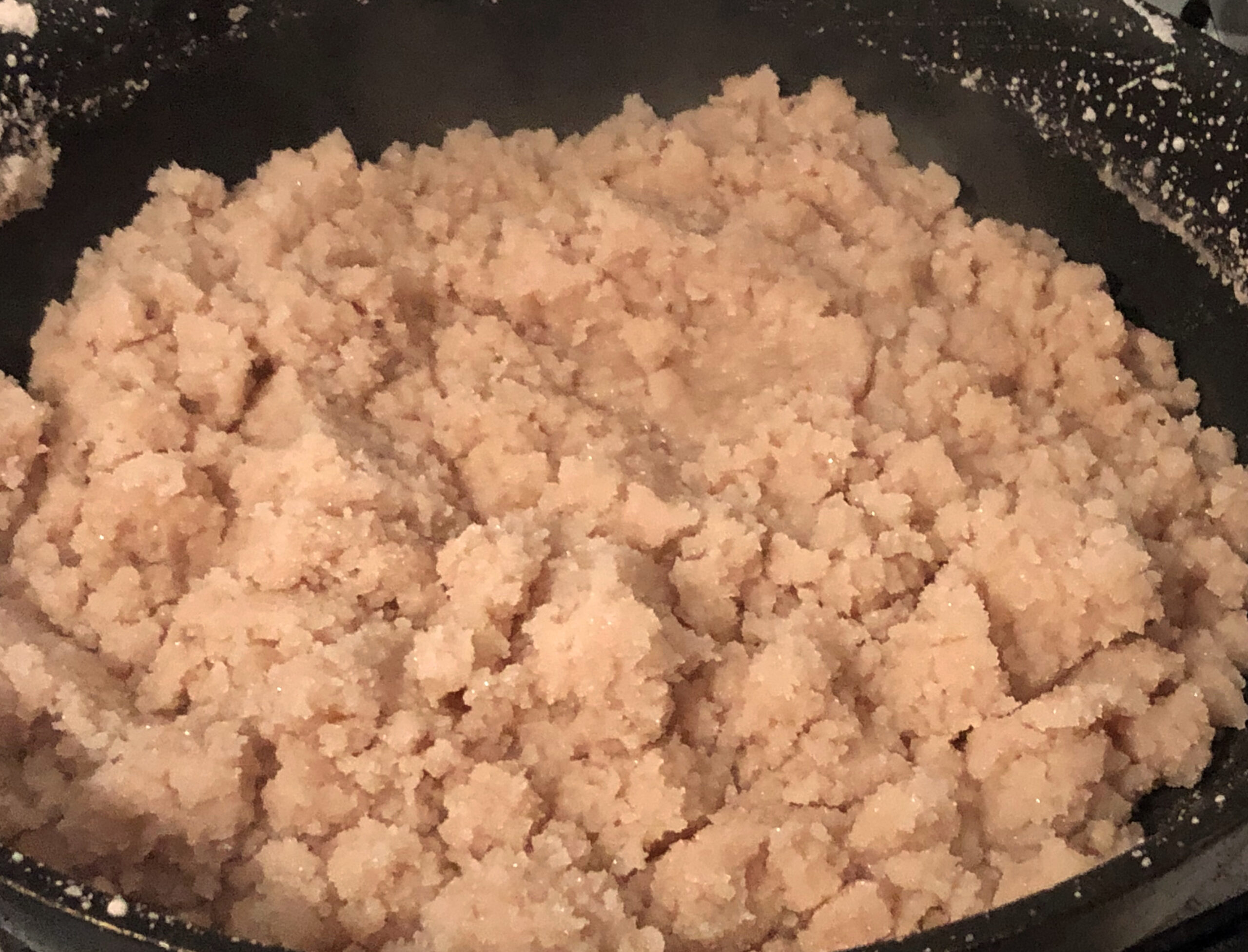

Ambergris was used as an ingredient in medicines, incense tablets, and perfumes. In cooking, it appears as a fumigant to scent a bowl or as a flavouring in dishes.