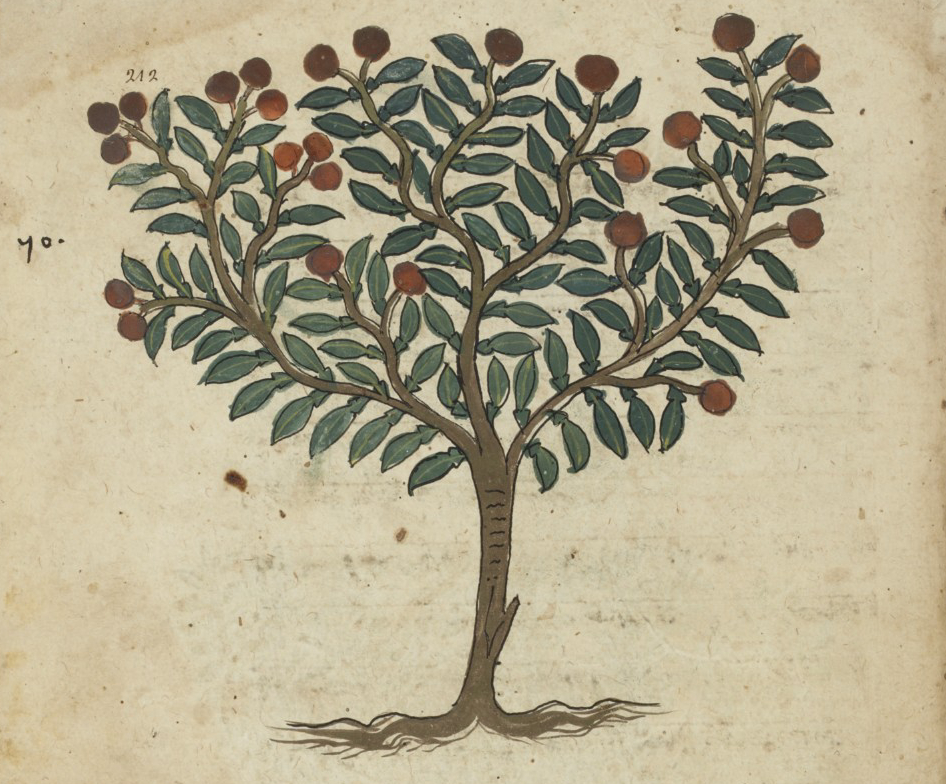

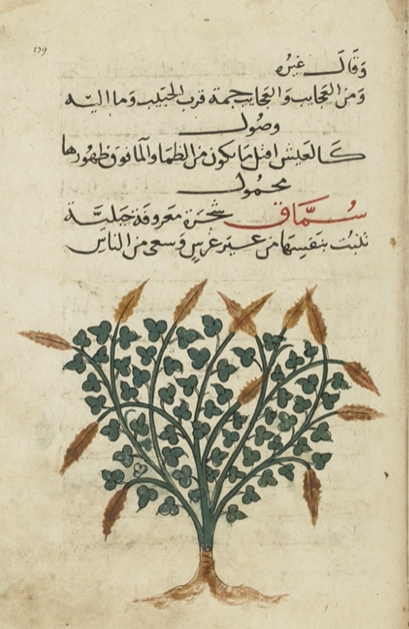

This aromatic (Cinnamomum cassia) is also known as Chinese cinnamon, in reference to its place of origin. The bark of the tree was already used in Antiquity in medicines and perfumes, though rarely in food. Ancient scholars believed it came from Arabia. Its preciousness was enhanced by its inaccessibility, which early on became legendary. The Greek historian Herodotus, for instance, recounts that cassia grows in a shallow lake guarded by bat-like creatures which attack the eyes of those cutting the plant. The Arabic term is derived from the Persian dār chīnī (دار چينى, ‘Chinese wood’) and was sometimes used interchangeably with salīkha (سليخة), but could also refer to ‘true’ (or Ceylon) cinnamon (قِرْة, qirfa). It is, in fact, not certain at all whether the present-day distinction between the two existed at the time. Some scholars only distinguished between dār ṣīnī and a qirfat dār ṣīnī, the latter being less powerful, and imported from China. In Arab cooking, it was one of the most widely used spices, and appears much more frequently than qirfa. Although often ground, recipes sometimes call for sticks (i.e. bark strips). A number of varieties (black, white, greenish, were known. Medicinally, it was used, among other things, to improve dim vision, as a cough remedy, diuretic, and even antidote against scorpion poison. Cassia differs from Ceylon cinnamon in its more reddish colour, rougher texture and stronger, more bitter taste.