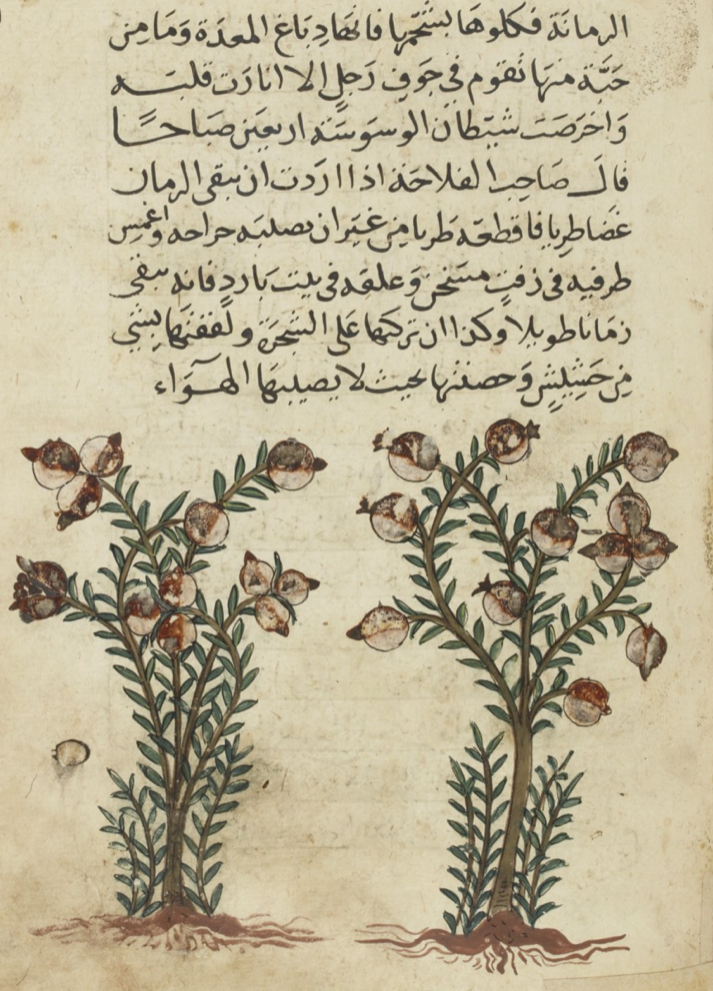

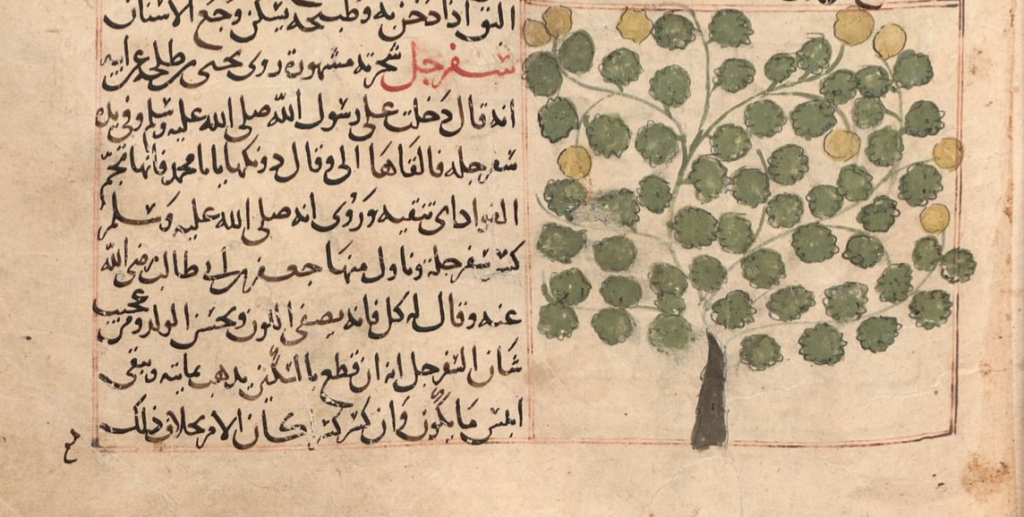

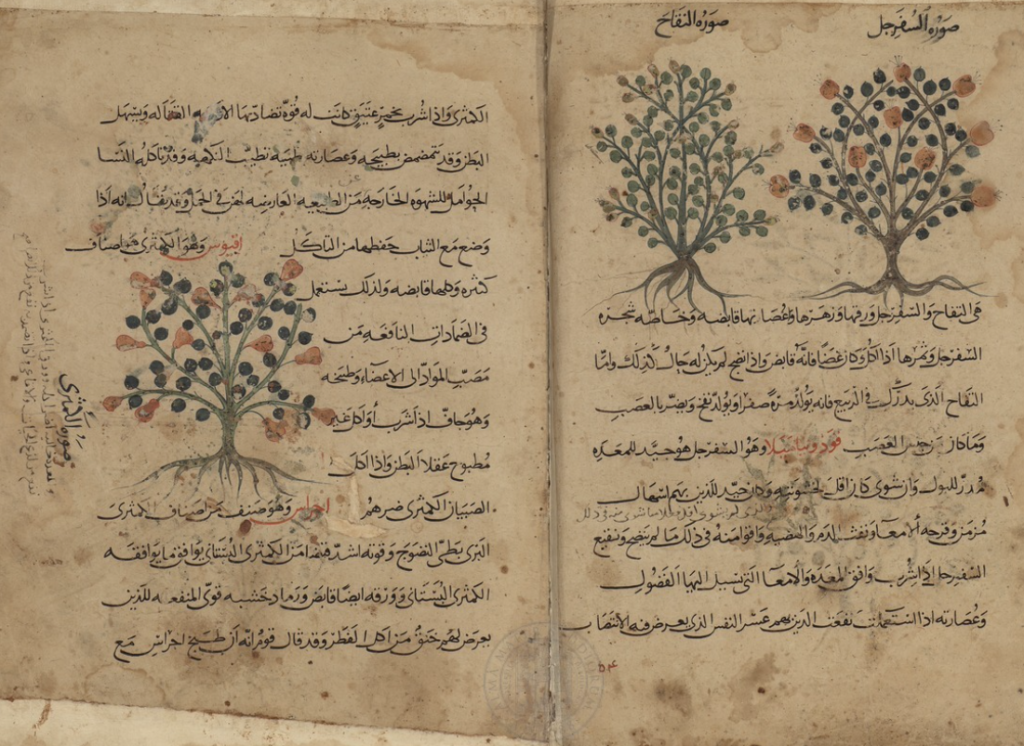

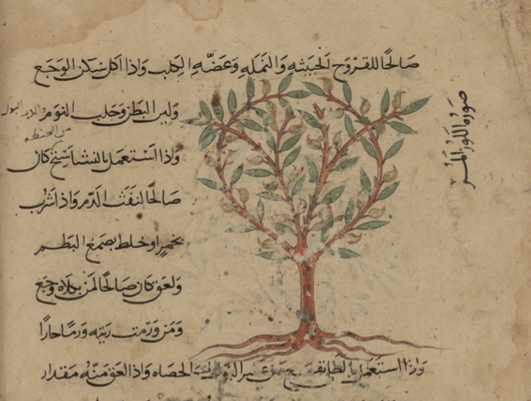

The pomegranate (Punica granatum) is probably native to Iran, but spread beyond its homeland very early on, to ancient Mesopotamia and then Egypt, where it arrived before the second millennium BC. The Sumerians knew it as nurma, which is the origin of the Persian anār (انار) as well as the Arabic rummān (رمّان). It continued to travel west along the Mediterranean, to Greece (where it is mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey) and can be found in the Iberian Peninsula and France before the start of the Christian era. The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder reports that in his day there were nine varieties of pomegranate.

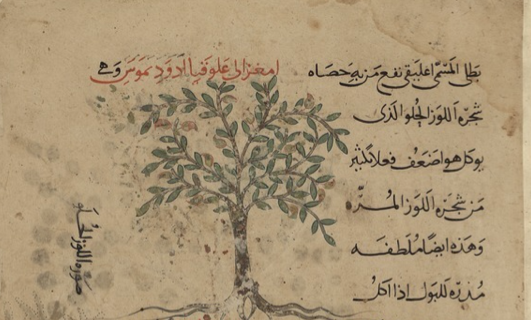

Classical physicians mention three kinds of pomegranates, based on their juice; sweet, winy and acidic. The juice, seeds, rind, and flowers were all used in medicinal applications for a variety of ailments. Known in Greek as roa (ρόα), it is the fruit’s latin name malum granatum (‘seed apple’) that has left a trace in many languages, besides English, such as in the French grenade, the Spanish granada, or the Italian melograno.

In the Muslim world, mainly sour and sweet pomegranates are mentioned, and the fruit has always been held in high esteem, not least because the sweet variety (حُلو, ḥulw) is mentioned several times in the Qur’ān and is one of the fruits of paradise. The pomegranates from Persia and Syria were particularly prized; the Umayyad Emir of Cordoba, ‘Abd al-Rahman, who was a keen collector of exotic fruit and plants, even sent agents out to Syria to acquire varieties grown there for his garden. According to the early 13th-century traveller to Egypt Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi, the pomegranates there were of the highest quality, even though they were never really sweet.

The fruit (both the seeds and juice) was an ingredient in many different types of dishes, from savoury to sweet, whereas the sour (حامض, hāmiḍ) pomegranate was used as an aromatic. Stews in which it is a key ingredient were known as rummāniyya (رمّانية), with chicken being the meat of choice in these recipes.

Both the fruit and peel of the pomegranate, but especially the juice, were used in the treatment of diarrhoea, fevers, cough, stomach and liver ailments, to curb yellow bile, and as a diuretic and anaphrodisiac (because of its acidity). The Persian-born physician al-Rāzī (d. 935), who became known in Europe as Rhazes, claimed that the sweet pomegranate bloats the stomach, whereas the sour variety is good against stomach inflammation. The juice made from the seeds of sour pomegranates cooked with honey is beneficial in the treatment of mouth and stomach ulcers. According to Ibn Buṭlān (11th century), the sweet pomegranate is an aphrodisiac, but flatulent (though this can be counteracted by eating sour pomegranate). The Jewish philosopher and physician Maimonides (d. 1204), for his part, believed that along with apple and quince, sucking pomegranate seeds after the meal is recommended for everyone as part of a healthy regimen.