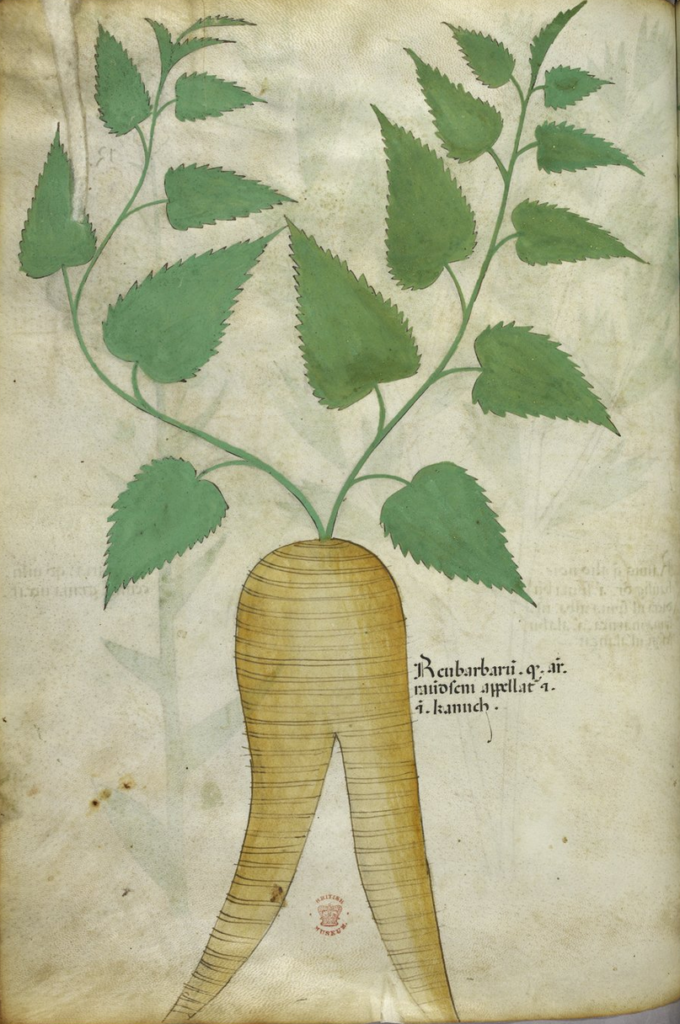

Rhubarb (Rheum ribes) originally hails from China but spread to the Mediterranean very early on as it was aready known in Greek antiquity. Dioscorides referred to it as ῥᾶ (rha), but added the variant ῥῆον (rheon), which is how Galen called it. The former name was said to come from the fact that it grew near the river Volga, known in Greek as rha, with Dioscorides specifying that it was ‘the lands above the Bosporus’. The word rheon may go back to the Persian word riwand (also rīwand, rāwand). There is no evidence that it was used in cooking in either ancient Greece or Rome, and it is not even mentioned in Pliny’s Natural History. Medicinally, Dioscorides suggested it was useful against intoxication, flatulence, fatigue, and hiccups, as well as a host of ailments affecting various parts of the body (spleen, liver, kidneys, bladder, chest, uterus, bowels). Previously, rhubarb had already been used in Chinese medicine, against blockages and to flush out the intestines, while a source from the Mongol era includes it in a potion to counter the effects of eating too much — or poisoned — fish!

It is in medieval Arab cuisine that rhubarb is first attested as food, though it is likely that this was a Persian influence; the Arabic word rībās (ريباس) is a borrowing from Persian (alongside ريواس, rewās) meaning ‘sorrel’ or ‘rhapontic’ (false rhubarb). Stews where it is the main ingredient were called rībāsiyya, the oldest recipe for which appears in an early 13th-century Baghdadi cookery book and calls for lamb, onion, rhubarb juice (extracted from the leafstalks), and almonds. In an earlier manual (10th century), rhubarb occurs only as an ingredient in a citron (pulp) stew (حماضية, ḥummāḍiyya), though the author does include a poem in praise of rībāsiyya.

The vegetable seems to have been much more popular in the Levant as most of the rhubarb recipes can be found in a 13th-century Syrian cookbook, which contains three chicken rhubarb stews (or, more precisely, fried chicken with a rhubarb sauce) and two variants with meat (probably lamb) and meatballs (made with rice and chickpeas). The rhubarb is usually boiled into a compote and then strained, though in one case it is pieces that are added to the dish. In fact, the vegetable never really gained popularity in the East, either (no doubt due to its bitter taste) and fell out of favour in Arab cooking for centuries and is today only used in Western-inspired dishes. The closest modern descendant of the rībāsiyya is the Iranian khorest-e rivās (خورشت ريواس), or perhaps this is what originally inspired the Arab dish?

In the medical literature, rhubarb is prescribed in a number of cases and its strength is sometimes compared to citron pulp. The 11th-century pharmacologist Ibn Jazla said that the rībāsiyya was made just like ḥummāḍiyya, and that it is good for weak stomachs, but is harmful to the chest, nerves, joints and sexual potency (though this can be remedied by eating a plump chicken!).

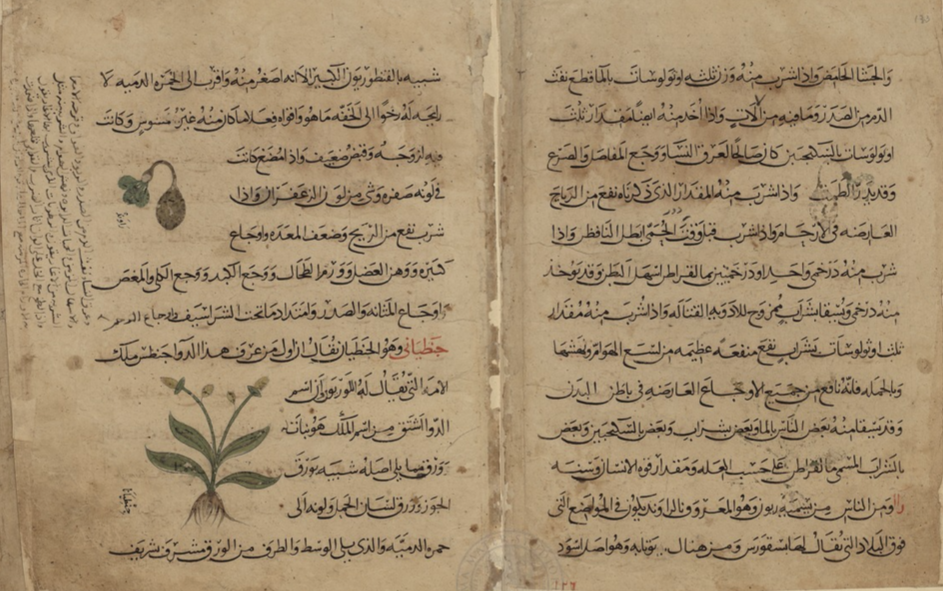

According to Ibn Sina (Avicenna), rhubarb (for which he uses the Persian riwand) is imported from China and is the root of a plant. His description of the medicinal uses of rhubarb owe much to Dioscorides as he, too, recommended it for use in skin conditions, liver and stomach illnesses, as well as hiccups, asthma, fevers and insect bites. Ibn Jazla claimed that the best variety came from the Persian mountains, and that it was useful against the plague, hangovers, to sharpen eyesight, as an anti-emetic and for its stomachic properties.

The Andalusian botanist Ibn al-Bayṭār (d. 1248) said that this plant did not grow anywhere in North Africa or al-Andalus, which, of course, explains why there are no recipes requiring it in medieval cookery books from those regions. He recommended administering it in a rob (رب, rubb), i.e. boiled down into a syrup, against palpitations, and vomiting. The Persian physician al-Samarqandi (d. 1222) added that rhubarb has a constipating effect.

If you want to see what a rībāsiyya looks like, check out this Sunday’s post discussing the recreation of a recipe from The Sultan’s Feast!