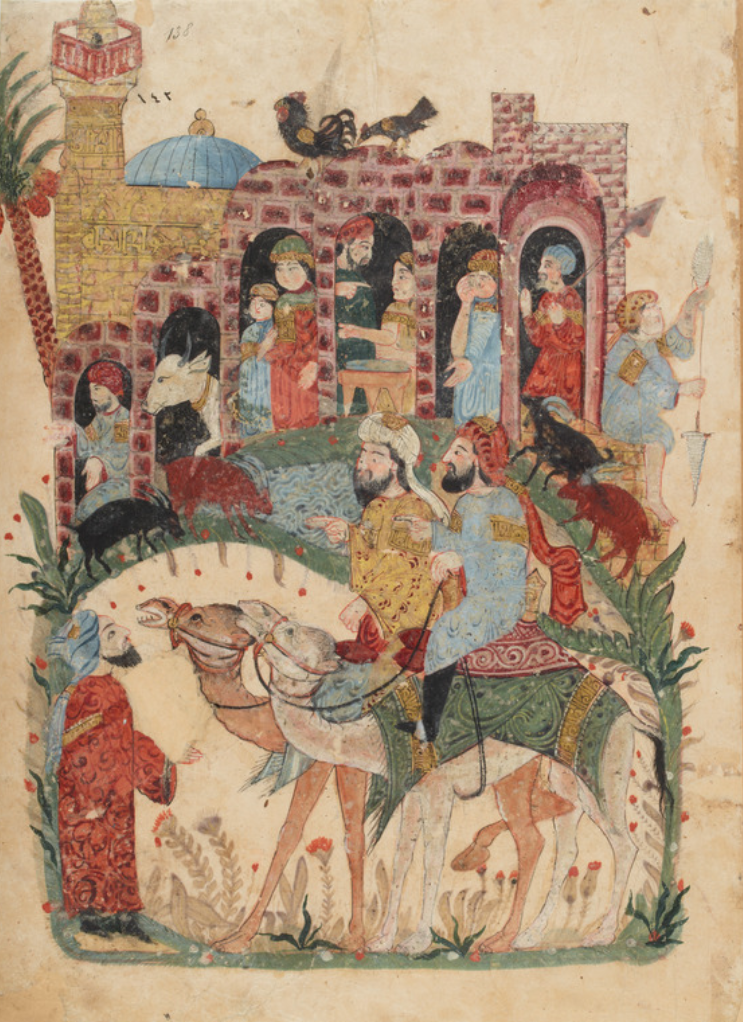

In the Middle Ages, markets were subject to a number of quality-control regulations, which were enforced by the market inspector, known as the muhtasib (محتسب). It is said that the Prophet Muhammad, himself, appointed the first officals with jurisdiction over the markets in Mecca and Medina. However, the office of the muhtasib appears not to have been formalized until the 9th century, during the Abbasid caliphate.

The importance attached to ensuring that market traders plied their wares in an ethical manner was such that a considerable number of manuals were produced across the Muslim world — from Muslim Spain to Syria and Iraq — outlining the muhtasib’s supervisory duties and responsibilities. These were, in fact, linked to the meaning of the word hisba (from which muhtasib is derived) as an injunction to promote good and forbid evil, which is incumbent upon every Muslim. In other words, to cheat customers is an unreligious — as well as an unethical and possibly criminal — thing to do. In many respects, the way the muhtasibs operated was very similar to today’s trading standards officers, and they provided a crucial public service.

Markets in the Muslim world contained a large number of food providers as most people ate out for most of their meals since the average home did not have the facilities for cooking, baking, etc. The public had a choice from amongst a dizzying array of specialised providers to satisfy the most varied and demanding of palates, with stalls specialising in fried fish, confectionery, freshly-made zulābiyya, cooked liver, harīsa (a meat porridge), cold snacks (bawārid), grilled and roast meats, sausages, cooked lentils and broad beans, sheep’s heads, etc. And it is in this area, of course, that the muhtasib‘s duties were, literally, of vital importance from a public health perspective. This also explains why they had to verify that traders had the required skills, as in the case of the syrup makers (sharrābiyūn), who also sold electuaries and other medicinal compounds, which could only be prepared from recognized pharmacological manuals.

The large range of potential issues that are mentioned in the hisba manuals clearly reveal that the market inspectors had their work cut out for them, as shown by the following examples from one of the hisba manuals from 12th-century Syria.

Naturally, the more precious the item, the more likely it will be tampered with. So, it is not surprising that saffron is often mentioned in this regard. Then, as now, it was blended with safflower, though other, far more unusual, tactics were also used. One of them involved using chicken breasts and beef boiled in water and then shredded before being dyed with saffron and mixed into the baskets. Other additives included starch or even ground glass! Similarly, camphor was apparently sometimes mixed with waste marble trimmings, or kneaded with resin. Honey, on the other hand, was frequently thinned with water, though this resulted in its resembling semolina in winter, and being watery in summer. As for turmeric, this was bulked up with ground pomegranate skins.

Bread was commonly adulterated by mixing beans, or chickpea and rice flour in with the wheat flour. Stews could be thickened with rice flour, semolina, taro, or starch. The sellers of the already-mentioned harīsa, which was a very popular market food, would not only thicken it with taro, but would instead of good-quality (lamb) meat use sheep’s head meat, or dried beef and camel meat. And like the contemporary visitor to an all-you-can-eat buffet, the medieval diner would be very much aware of the possibility that the harīsa might contain the left-over meat from the previous day — or the one before that!

The manuals give clear instructions on how to identify fraudulent acts, such as changes in colour, consistency, and taste of foodstuffs and ingredients, with the muhtasib being assisted by helpers, who would report on any suspicious behaviour. For instance, in order to detect fraudulent musk — another very expensive commodity — the inspector should put his lips to it; if it is pure musk, he should get a sharp sensation, like fire, in his mouth. If he does not, then the musk has been tampered with. The inspector would also take pre-emptive measures, such as putting a seal on food items, to prevent any subsequent tampering.

Another key area revolved around measures and weights, and muhtasibs went around verifying that traders used the right weights and did not short-change the unsuspecting punter.

When rules were broken, there would naturally follow a punishment, which the inspectors were empowered to carry out. However, the manuals encouraged them to rely on deterrence and reprimand, and to be lenient for first offenders, while the penalty should be commensurate with the crime. The manual lists the muhtasib‘s main tools of the trade, so to speak, as being the whip and the turtur (طرطور), a tall conical cap, which were displayed at his booth in the market, by way of deterrent. In serious cases, or repeat offending, the penalties would be flogging and/or public pillory, with the culprit being forced to wear the turtur as a kind of dunce cap, and paraded about town.

But it was not just unscrupulous business practices that fell within the muhtasib‘s remit, which was, after all, to uphold moral conduct, and so he would also intervene in other matters that infringed upon public decency, such as the drinking of alcohol, or unmarried/ unrelated men and women consorting.