In the “Tale of the Porter and the Three Ladies” (الحمّال والصبايا الثلاثة, al-ḥammāl wa-l-ṣubāyā al-thalātha) from the 1001 Nights (ألف ليلة وليلة, alf layla wa layla), also known in the West as the Arabian Nights, one of the protagonists praises the quince as it ‘puts to shame the scent of musk and ambergris’, citing the following verse by an anonymous poet:

”The quince combines all of the pleasures of mankind

It is more famous than any other fruit.

It has the taste of wine and the fragrance of musk,

Golden hued, and rounded like the full moon.”

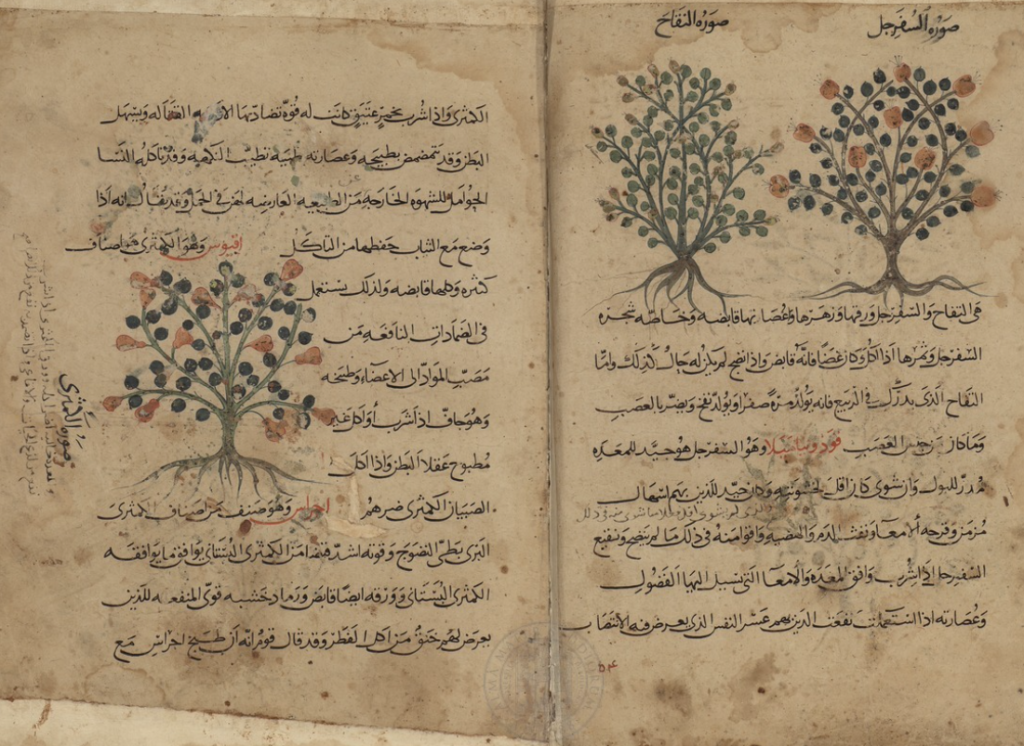

The origins of the quince (Cydonia oblonga) are shrouded in mystery, but it may have been ancient Mesopotamia; the Arabic word safarjal (سفرجل), in fact, goes back to the Akkadian supurgillu (šapargillu). The Greeks knew two types of quince (sour and sweet), but often considered it a type of apple (mêlon, μῆλον), known as kudonion (κυδώνιον), after its alleged birth place, the Cretan town of Cydonia. In Latin, too, the word for apple (malum) denoted quince (and sometimes even pomegranates or peaches).

Quinces were used in a variety of preparations (often with honey), such as jams, conserves, syrup, or fermented into a wine. When packed in honey, the resulting preserve was known as mêlomeli (μηλόμελι, ‘apple/quince honey’). The first-century botanist Dioscorides said that it was prepared by deseeding quinces and then fully immersing them in honey; after a year, the mixture becomes smooth and resembles wine mixed with honey. It is the linguistic ancestor, by way of Latin, of marmelo, the Portuguese for ‘quince’. Another Portuguese word denoting a quince preserve (quince cheese), marmelada, travelled further westward, and gave English its word for the breakfast favourite marmalade (though today this is associated with citrus fruits). Physicians recommended baking quinces before eating them, and due to their astringent property prescribed them, for instance, as an anti-diarrhoetic. In addition to a quince preserve which called for the whole fruit, including the stems and leaves, the Roman cookery book by Apicius (4th c.) includes recipes for a few stews with quince, leeks and honey, or beef. More unusually, he also gives a fish recipe requiring cooked quinces, pepper, lovage, mint, coriander, rue, honey and wine.

Despite the praise lavished on the quince in the story from the 1001 Nights, it was not used very often in medieval Arab cooking, with fewer than forty recipes requiring it. In what is considered the oldest Arabic culinary cookbook (10th c.), quince appears mostly in medicinal conserves, syrups or beverages, as well as in a chicken stew (زيرباجة, zīrbāja), and a preserved lamb recipe (أهلام, ahlām). In the thirteenth century, the safarjaliyya (سفرجلية), or quince stew (made with lamb), made its first appearance in cookery books from across the Muslim world: Egypt, Baghdad, al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), North Africa, and Syria. It is an Andalusian recipe for quince jelly that is the direct ancestor of both the Portuguese marmelada and its Spanish cousin dulce de membrillo. Quince was used in meat stews, murrī (a fermented condiment), and pickles. Like before, the quince drinks (often with lemon) and conserves were considered primarily medicinal. In dishes, apples are frequently paired with quince. In 15th-century Egypt, the safarjaliyya was still part of the repertoire, and according to The Sultan’s Feast, quinces should be preserved by rolling them in fig leaves coated with clay and then drying them out in the sun.

Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) suggested grilling quinces after scooping out the seeds, filling the cavity with honey and then covering the fruit with clay before putting them over hot embers. He recommended it as an anti-emetic, and as a cure for dysentry and hangovers. He also added that one can prevent a hangover by drinking quince syrup after overindulging in wine. The highly astringent qualities of quince strengthen the stomach and Ibn Sīnā advised eating them after meals.

The famous 11th-century peripatetic physician Ibn Butlan (ابن بطلان) advised eating quince both before and after meals as the bits block openings in between the teeth, thus preventing food from lodging in there. He held that quince purifies the stomach when taken before a meal, and loosens the bowels when eaten afterwards. In addition, quince also acts as a diuretic, but can be harmful to the nerves.