Pine nuts, mainly the fruit of the Mediterranean stone pine (Pinus pinea), were already used in both Greek and Roman cuisine; Apicius has nine recipes requiring them, mainly in sauces and dips.

In Arabic, ṣanawbar (صنوبر) may refer to pines in general (Pinaceae genus), to the stone pine as well as to the pine nuts (more correctly ḥabb al-ṣanawbar/حب الصنوبر). The pine was also sometimes known as fīṭis (فيطس, a calque of the Greek πίτυς).

Pine nuts were used very sparingly in the Near Eastern cookery books , and appear only in an Abbasid manual (mainly in sweets) and one from Mamluk Egypt (in a murrī recipe). They are conspicuous by their absence from medieval Syrian cooking. Things are very different on the Western Mediterranean, however, and there are no fewer than twenty recipes from al-Andalus with pine nuts — as an ingredient in savoury stews and sweets (including the cornes de gazelle), and as a garnish (alongside sugar and other nuts for sweets).

Medieval scholars considered the pine tree the female of the cedar, while large pine nuts were sometimes known as jillawz (جلوز), even though this usually meant ‘hazelnuts’. In Islamic medicine, pine nuts were considered dissolving and useful for weak bodies, against pus and bleeding, and to strengthen the stomach when applied as a poultice together with wormwood. The were also thought to increase semen and, according to Dāwūd al-Antākī (16th c.), ‘stirred the two desires’ (يهيج الشهوتين , yuhayyiju al-shahwatayn), that is to say, appetite and lust. However, pine nuts were said to harm the head and irritate the stomach, possibly even causing colic.

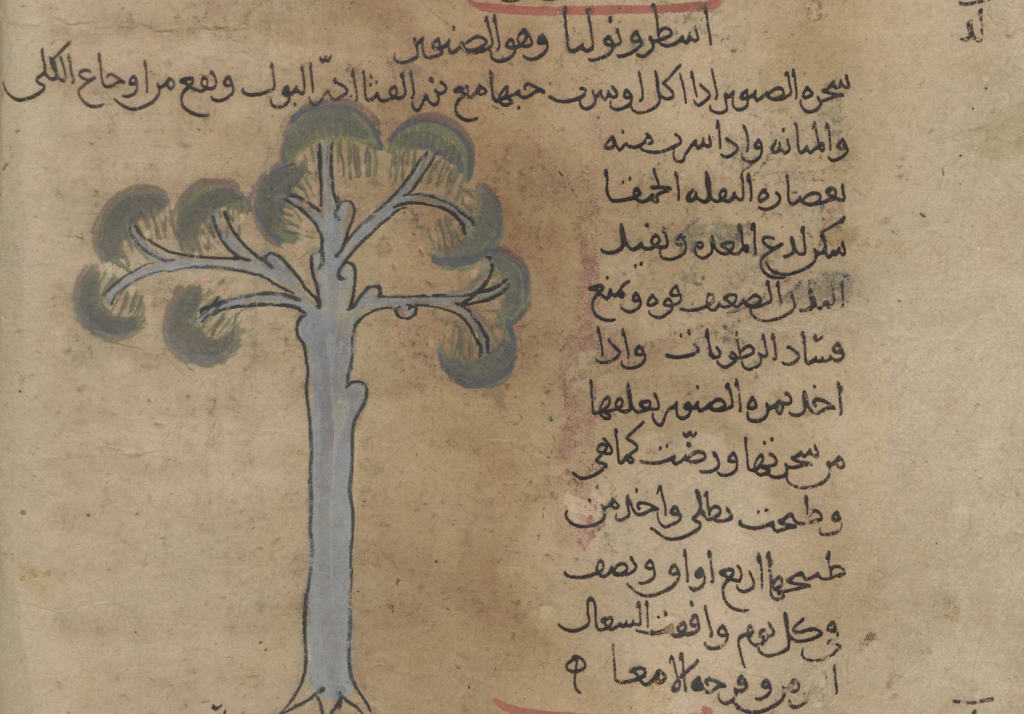

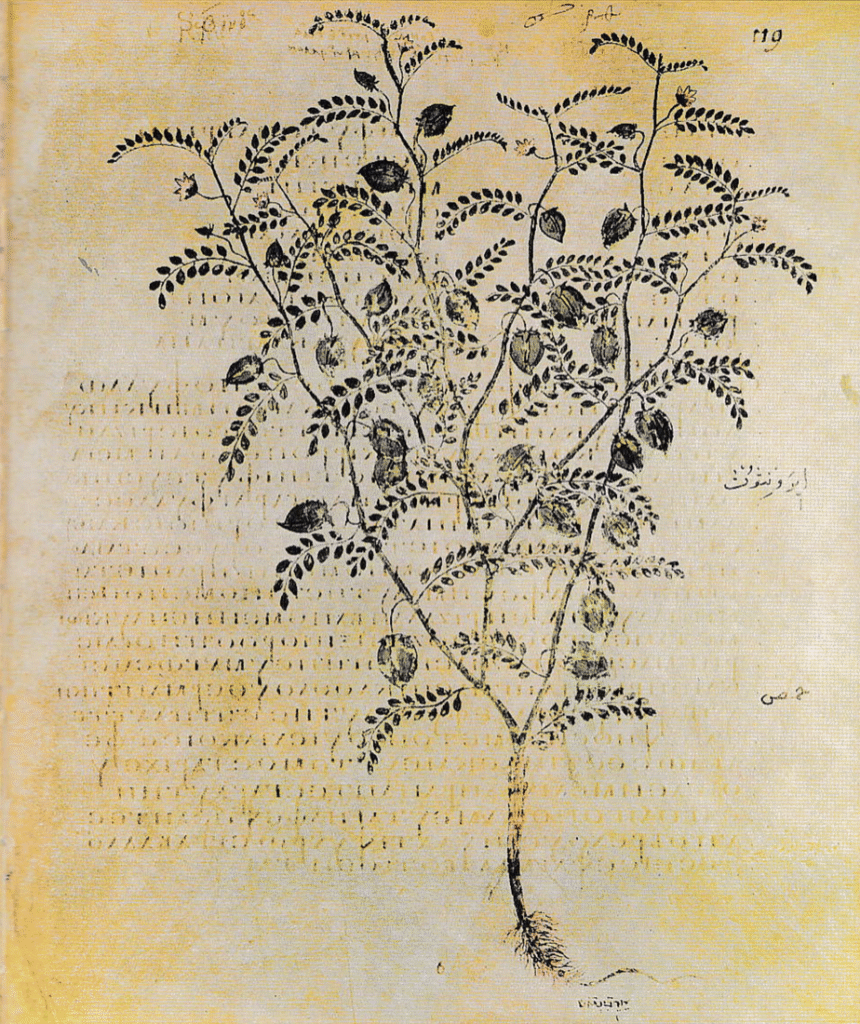

Interestingly enough, the Arabic translation of Dioscorides’ Materia medica by the famous scholar Hunayn Ibn Ishaq (9th century) from which the illustration below has been culled, has only one (abridged) paragraph of the much longer entry on the pine tree (πίτυς) in the original Greek. Also, the tree is called usṭrūnūlbā, a corruption of strobilos (στρόβιλος), which Dioscorides mentions as a pine variety, and is sometimes identified as the Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra). The text reads: “When the seeds of the pine tree (sanawbar) are eaten and drunk with cucumber seeds (the original also adds grape juice) they have a diuretic effect and are useful against kidney and bladder pains. If drunk with purslane juice, the pine seeds relieve stinging stomach pains, and are useful to strengthen weak bodies. They prevent the corruption of moistness. When the pine nuts are taken when hanging from the tree and ground, they are applied in a poultice. When four ūqiyas (ounces) are taken from the grounds each day, it stops chronic coughs and intestinal ulcers (in the source text it says that they should be boiled in grape juice).”