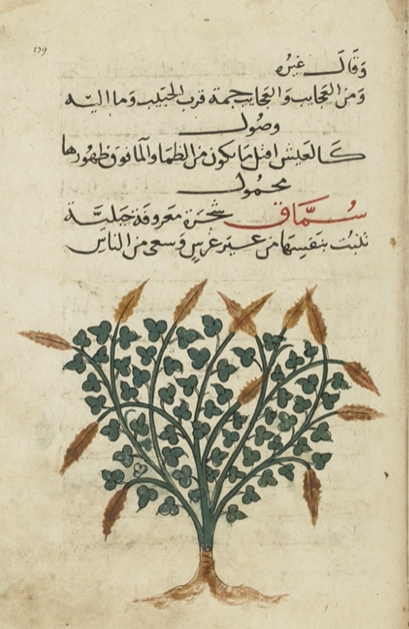

One of the emblematic spices used in Abbasid cuisine, sumac (Rhus coriaria) was already used in cooking by the ancient Greeks, who imported it from Syria. In mediaeval Arab cuisine, dried sumac berries (as well as husks), were used pounded, or macerated, and strained to make sumac juice, which was used as a marinade for meat, as a cooking liquid, souring ingredient (chicken and lamb stews), or to dye dishes red. The juice of sumac berries was also sometimes boiled down to produce a more condensed mixture, known as sumac dibs, which could be used for souring dishes. Its taste is perhaps best described as a mixture of lemon and vinegar. Scholars distinguished between two kinds of sumac, Khorasani and Syrian, the latter of which is smaller and red like lentil. In Islamic medicine, sumac was said to be useful against bleeding, tooth-ache, nausea, and the spread of ulcers. The extract can be used to colour the hair black. Physcians warned that it causes constipation, and thus dishes containing sumac were recommended for those suffering from diarrhoea. Apparently, the caliph Harun al-Rashid was very partial to the taste, particularly in savoury sumac stews (summāqiyya).