Also known today by its Hindi name hing, asafoetida (Ferula Assa-foetida) refers to the pungent resinous gum from a giant fennel which grows in the wild in what is today Iran and Afghanistan. Its English name derives from the Persian āzā (ازا, ‘mastic’) combined with the feminine Latin adjective foetida (‘smelly’), in reference to its strong odour, which also explains its less than flattering names and link with the devil in other languages, as in ‘devil’s dung’ in English or merde du diable (‘devil’s excrement’) in French .

It has a very long history and is already mentioned in Akkadian texts as nukhurtu and was used in food in ancient Iran. In the Middle Ages, it was cropped in Persia for export. It was also known in European Antiquity; the Greeks considered it a variety of silphion, which unfortunately has defied identification and has been extinct for centuries. In Roman times, the juice was known as laser or laserpitium, and is called for in several dishes in Apicius’ cookery book.

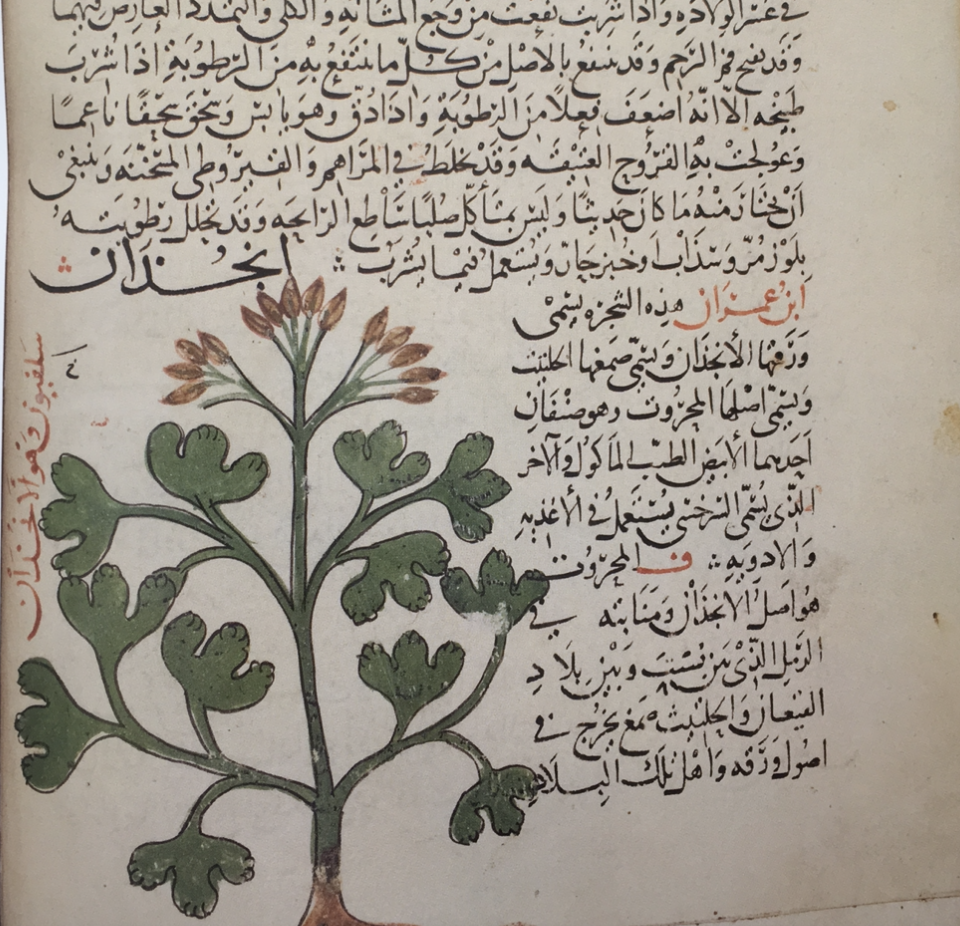

The Arabic anjudān/anjudhān is a borrowing from Persian and refers to the whole plant or its leaves, whereas ḥiltīt (حلتيت) denoted the gum and maḥrūt (محروت) the root. Another word for the latter was ushturghāz/ushturghār (أشترغاز/أشترغار), another Persian borrowing (from ushtur, ‘camel’; khār, ‘thorn’), though this was sometimes identified as the root of lovage (kāshim, Levisticum officinale). Some scholars mention two kinds of anjudān, one black and foul smelling, and a white fragrant one used in cooking.

In medieval Arab cooking asafoetida is used very sparingly across the literature, and is missing from several recipe books. The plant was not known in North Africa or al-Andalus. One of the earliest recipes requires both the leaves and roots with fish and is attributed to the Abbasid gourmet caliph Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi (d. 839). In a 13th-century text, asafoetida leaves are used, together with a a whole raft of aromatics in a seasoned salt mixture. The root was also pickled, and a recipe is included in a 15th-century Egyptian cookery book.

Medicinally, asafoetida was thought to make the stomach rough, remove bad breath, fight poisons and bring on menstrual flow, as well as being a diuretic and useful against joint pains. The root, however, was though to be more difficult to digest and more harmful to the stomach than the rensin.

Today, asafoetida is primarily associated with southeast Asian cuisines where it is used in many dishes (particularly as a substitute for garlic and onions), and is usually sold in powdered form, either pure or mixed with rice flour.