The sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) was already well known in ancient Greece, and was called καστανία (the etymon of the Latin castanea) and ‘King’s acorns’ (διοσβάλανοι), whereas Dioscorides called them ‘Sardian acorns’ (βάλανος Σαρδιανή). They were often eaten boiled or roasted as a snack accompanying wine. Chestnut flour was sometimes used to make a bread, though this was considered of poor quality. There is only one recipe from Roman times for cooked and mashed chestnuts in a seasoned honey and vinegar sauce.

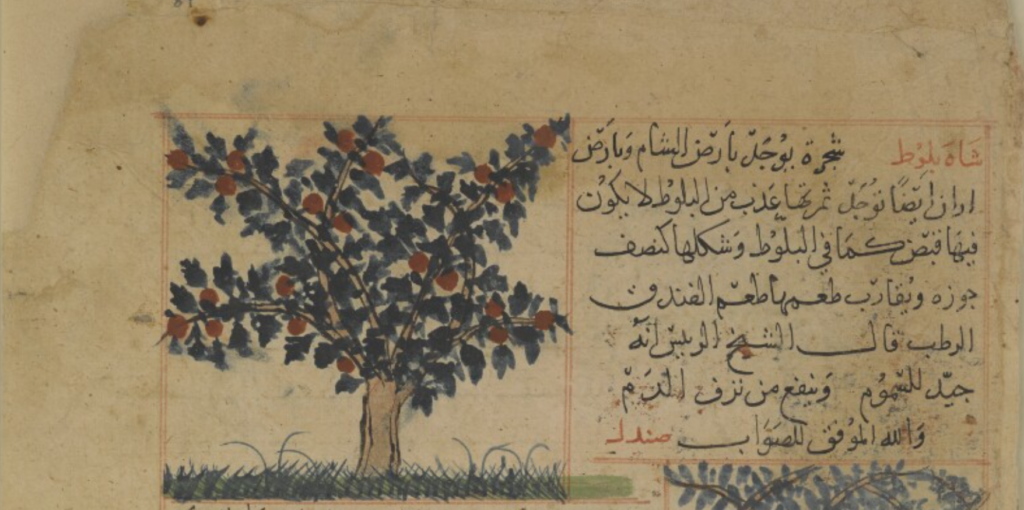

In medieval Arabic literature the chestnut was usually known as ‘shāhballūt‘ (شاه بلّوط), a Persian borrowing (itself a calque from the Greek διοσβάλανοι), alongside kastana (كستنة) and, in al-Andalus, qasṭal (قسطل). Its use in cooking was quite rare, with only one Near Eastern recipe. In the Andalusian recipe collections, chestnuts are called for in a total of four recipes. Interestingly enough, in one case, a stew with chicken meatballs, the recipe is listed as an ‘Eastern dish’. The increased use of the sweet chestnut in the Muslim West can be explained by that it was native to the area — indeed, to this day, the sweet chestnut is also known as ‘Spanish chestnut’.

Muslim physicians held that the chestnut were extremely nutritious — in fact more so than any other ‘grains’ — and that it was useful against poisons. However, it was deemed to be very slow to digest and should not be used for people, but only as pig feed.