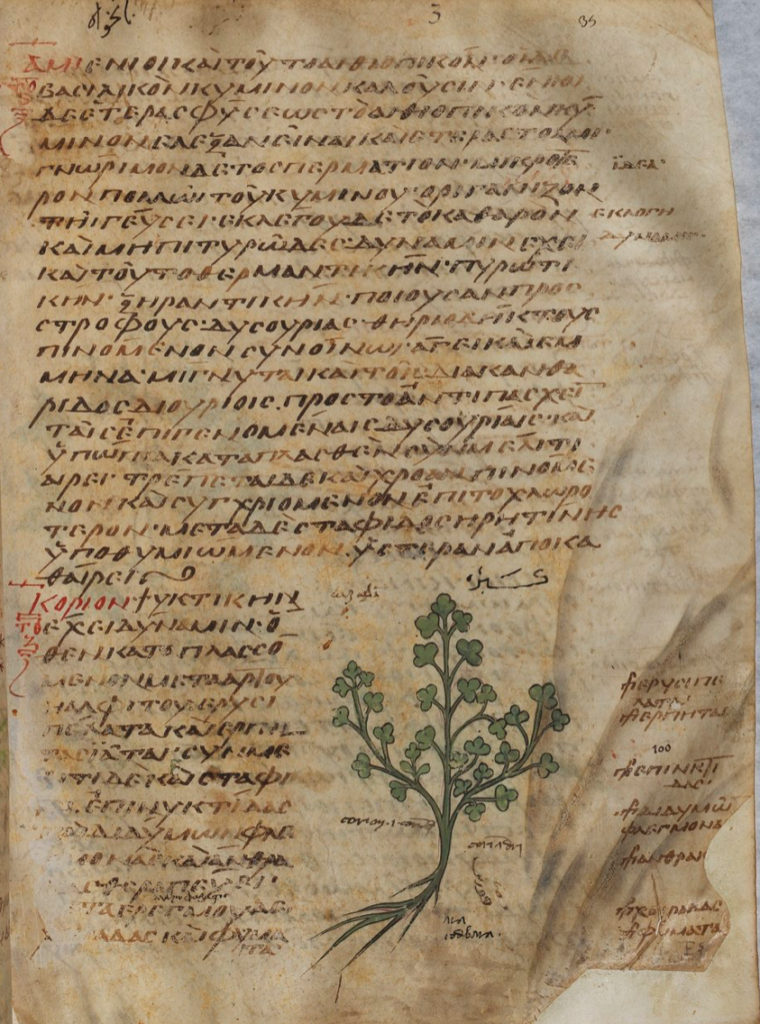

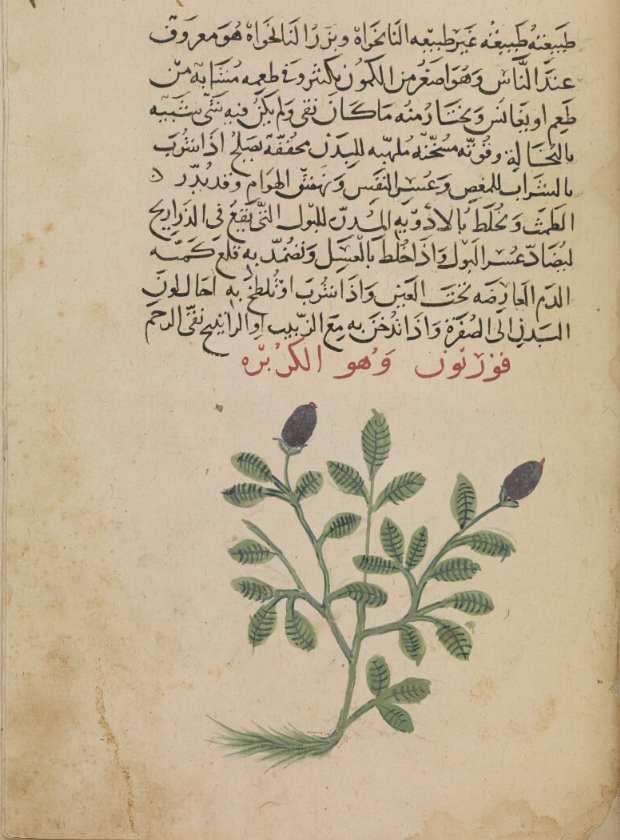

Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) is native to the eastern Mediterranean basin, and its use in cooking is already attested in ancient Mesopotamia, where it can be found often in conjunction with cumin and nigella. Its name in Akkadian, kisibirru, is the origin of the Arabic kuzbara (كزبرة), which has the variant spellings kusbara (كسبرة) and kusfara (كسفرة). It was also in use in Ancient Egypt and Greece by at least the 2nd millennium BCE, and later became a mainstay in Roman cuisine — nearly one-fifth of Apicius’ recipes call for coriander, known in Latin as coriandrum (or coliandrum), derived from the Greek koriannon. In English, its name varies depending on which side of the Atlantic you’re on; in the UK, it is known as coriander, whereas in North America ‘cilantro’ is preferred, which goes back to the Spanish culantro (itself a descendant of coliandrum), but this only refers to the leaf, not the seeds.

Usually it is the leaves and fruit of the plant that appear in cooking, with the root being used in medicine only. Today, it is only east Asian cuisines — especially Thai — that use the root as a cooking ingredient. In medieval Arab cuisine, coriander was one of the most used spices, both dried (seeds) and fresh, and it is not uncommon for recipes to require a combination of both. In a 13th-century anonymous Andalusian treatise, dried coriander is said to suit all food, but especially tafāyās (stews) and stuffed (maḥshī) dishes. In Spain, coriander obtained a religious connotation it did not have elsewhere in the Muslim world in that it was considered a ‘Muslim’ herb, just as parsely was considered a ‘Christian’ herb. Indeed, after the Reconquista, the mere fact of eating coriander was considered an un-Christian thing.

Islamic scholars held that fresh coriander is astringent, strengthens the stomach, staunches bleeding, and is useful against dizziness and epilepsy caused by bilious or phlegmatic fevers. Al-Samarqandī (d. 1222) recommended roasted coriander against palpitations, ulcers and hot swellings, but warned that dried coriander decreases sexual potency and dries out semen (though Ibn Sīnā attributed anaphrodisiac effects to both the fresh and dried varieties). He also claimed fresh coriander should not be eaten by itself, but used to season cooked dishes, while its potency becomes greatly enhanced when used with sumac. Also, when meat is soaked in vinegar and seasoned with coriander, it is more easily digested. Eating too much coriander leads to dim vision and mental confusion.

According to the Andalusian pharmacologist Ibn Khalṣūn (13th c.), (fresh) coriander strengthened the heart of those with hot temperaments (along with, for instance, saffron and caraway), whereas pigeons should be cooked in it (together with vinegar). He also recommended eating coriander with fatty meats and strong spices. As dried coriander keeps food in the stomach until it has been digested, it should be used sparingly, especially in rich dishes. Coriander was also thought to be constipating, while alleviating inflammations in the stomach.

Such is its importance in Arab cooking, even today, that in some North African dialects (e.g. Tunisia), it is also known, simply, as tābil (‘seasoning’).