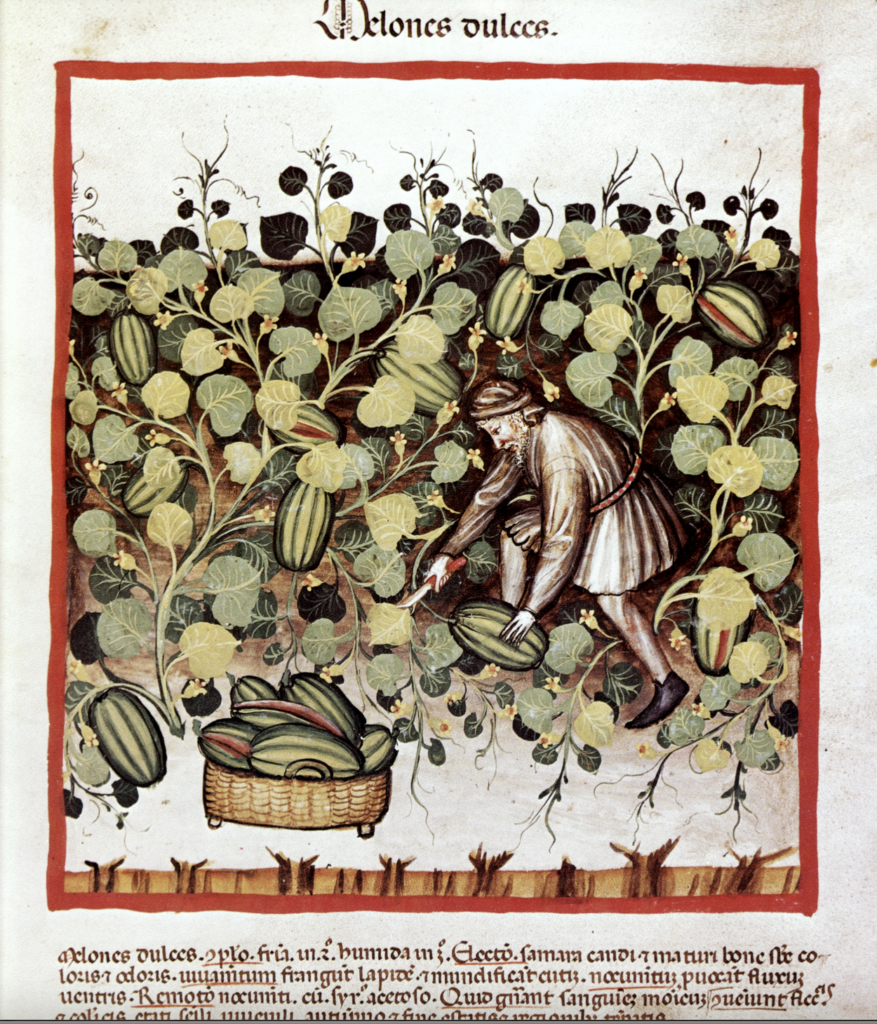

The exact place of origin of the common melon (Cucumis melo) is unidentified to date but it is widely accepted that it somewhere in the area between the Mediterranean and northern India. The variety eaten in Antiquity was the cucumber-shaped chate melon (Cucumis melo var. Chate), rather than the sweet fruit of today.

The watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) is an unrelated species that is native of (west) Africa, as is its sister species, the colocynth (Citrullus colocynthis) — most commonly known as ḥanẓal (حنظل) in Arabic –, which was never eaten, due to its bitterness. The oldest attested use of the watermelon in the Mediterranean may go back to Egypt in the second millennium BCE. Indeed, the Arabic word for it, biṭṭīkh (بطّيخ), is a descendant of the ancient Egyptian bddw-k’, which became pi-betuke (pi-betikhe) in Coptic, though it has been suggested that this actually denoted the aubergine, and was only later transferred to the watermelon. The depictions of the fruit have also been called into doubt and are said to show the colocynth, rather than the watermelon. The wild ancestor of the watermelon was very different from today’s varieties, particularly in that it was more bitter than sweet.

A more plausible hypothesis of the development of the watermelon is that it travelled eastward and after cultivation in India returned west, courtesy of the Arab merchants, who also introduced the fruit to Europe. Support for this hypothesis may be found in the fact that medieval Arabic scholars often distinguished between a number of watermelon varieties, all of which hail from the east: Falasṭīnī (Palestinian), Shāmī (Syrian), Hindī (Indian) and Sindī (from the Sind, i.e. north-west India).

In Arabic, dullāʿ (دلاع) and biṭṭīkh were not uncommonly used interchangeably for both the common melon and the watermelon; the former word is of Berber origin and explains why this is the still the most common word for watermelon in North African vernaculars. The term shammām (شمّام) is applied only to the sweet (cantaloupe) melon.

In the medieval Arabic culinary tradition, melons are used relatively rarely. There are some savoury recipes for snake melon (‘ajjūr, عجّور) used in savoury recipes in Syrian and Egyptian collections, whereas the latter also contain a chate melon confection. In the early Abbasid tradition, the watermelon appears in some judhāba and fālūdhaj recipes. Additionally, the rind was used in hand-washing powders, whereas the dried ground peel was said to make food cook quickly.

Medicinally, opinions on the benefits of watermelon varied somewhat. According to some, the watermelon was slow to be digested and generates thick blood. Others held that all kinds of melon are beneficial for coughs, kidneys, and ulcers in the lungs and bladder. Al-Qazwini recommended soaking watermelon seeds in honey and milk to ensure its fruit will be very sweet.

The watermelon enjoyed much favour in religion as well, as shown by the following hadith (saying of the Prophet): “Enjoy the watermelon and its fruit, for its juice is a mercy, and its sweetness is like the sweetness of faith. Whoever takes a morsel of watermelon, Allah writes for him seventy thousand good deeds and erases from him seventy thousand misdeeds.”