One of the oldest and most utilised spices in history, pepper (Piper nigrum) was originally grown on the Malabar coast (southwest India). It starts as berries of a perennial climbing vine which are harvested as soon as they ripen and have turned red. The peppercorns are then left out to dry out in the sun, after which they turn black. For white pepper, the berries are left on the vine longer and are then soaked so that the white seed can be extracted more easily before drying it. The white variety is less fragrant and aromatic.

In Greek Antiquity, where pepper is first attested in around 400BCE, only two kinds were known, black and ‘long pepper’ (Piper longum). The latter is another species of the pepper family, and tends to refer to the variety grown in the Himalayas and southern India. There is also a species grown in Malaysia, and known as ‘Javanese’ long pepper (Piper retrofractum). It is, in fact, long pepper that was most used in the Mediterranean basin, and it is its Sanskrit name, pipali, which is the origin of the Greek peperi, and thus the English ‘pepper.’

In Roman times, the spice really came into its own and the naturalist Pliny (1st c. CE) refers to black, white and long pepper, adding that the last cost twice as much as the second, which, in turn, was more expensive than the black. In Apicius’ cookery book (4th c.), pepper is the single-most important spice, and is used in nearly 90% of dishes.

In the Arabic-speaking world, the same three varieties of pepper (fulful‘, filfil)) were known and used: black (aswad), white (abyaḍ), and long pepper (dār fulful < Persian). It was also sometimes referred to as ḥabb Hindī (‘Indian seeds’) and bābārī (a Greek borrowing). The Arabic fulful goes back to the above Sanskrit word, via Persian.

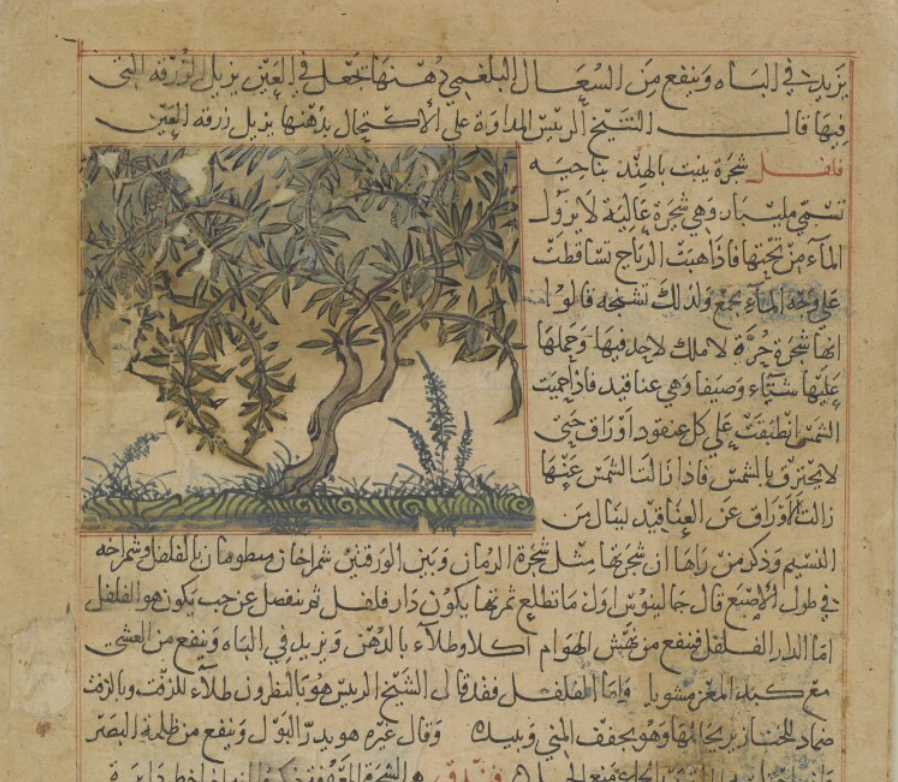

According to the oldest Arabic geographical manual, pepper was sourced from Kīlah, which has been identified as Kra, in the Malay Peninsula. In his ‘Wonders of Creation‘ (see illustration below), al-Qazwini explains that pepper comes from a tall tree that grows in India in the region called Malabar (Malibar, مليبار), close to the water; it bears fruit in summer and winter, and its grains are blown in the water by the wind, after which they shrink. The Andalusian botanist Ibn al-Baytar (13th c.) lists a number of other members of the pepper family (seven in total), including fulful al-Ṣaqāliba (‘Slav pepper’) and fulful al-mā’ (‘water pepper’).

In cooking, black pepper was one of the most used spices and is called for — usually ground — in many savoury dishes, condiments, etc. A 15th-century Egyptian author said that it has a powerful effect and enhances the smell of the food, and thus one does not need a large quantity of it. Furthermore, pepper was apparently also used in dishes containing cassia and galangal in order to reduce the flavour of the these spices. In Islamic medicine, black pepper was used extensively, including as a digestive, appetizer, diuretic, and aphrodisiac.

White pepper was used very sparingly in medieval Arab cuisine, and according to a 12th-author, it was only used for medicinal purposes. Long pepper, too, appears relatively rarely; it is found in a number of recipes in a 10th-century Abbasid treatise and just twice in a 13th-century Syrian collection book, but is absent from other cookery manuals. However, long pepper was not infrequently used in medicinal compounds.

In medieval European cuisines, long pepper was used extensively but fell out of favour by the end of the 17th century and has remained conspicuous by its absence from the European culinary repertoire. Today, long pepper tends to be associated with Asian cuisines.