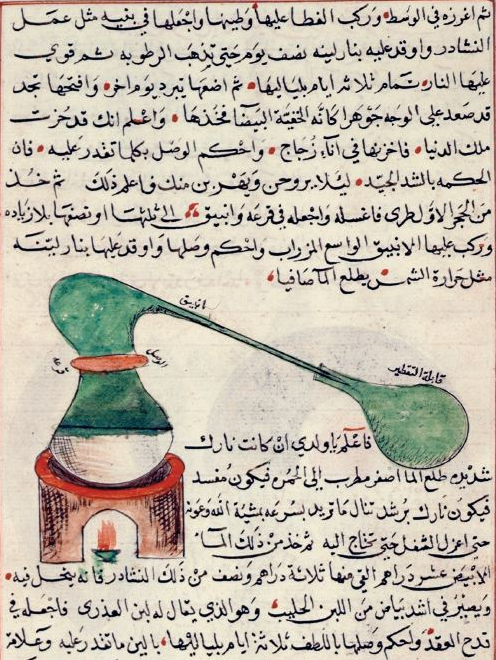

Rose water is one of the staple ingredients in medieval Arab cooking and was obtained through distillation (تصعيد, tas’īd) in what is known as an alembic. The word goes back to the Arabic al-anbīq (الأنبيق), itself a transliteration of the Greek ambix (ἄμβιξ). While, today, alembic refers to the still as a whole, al-anbīq only referred to the top, or cap, placed on the vessel that is heated up, known as the ‘cucurbit’ (قرعة, qar’a). The joint (وصل, wasl) between the components is sealed in order to make it watertight. As the drawing below shows, the anbīq is then connected with another vessel, the ‘recipient’ (قابلة, qābila) of the distillate (تقطير, taqtīr). Though invented in ancient Greece in the 4th-century BCE, the instrument was perfected and used extensively by Islamic chemists and alchemists, such as the Persian-born alchemist Jabir Ibn Hayyan (جابر ابن حيان), who later became known in the Christian West by his latinized name of Geber.

The distillation could be done either by the cucurbit being in direct contact with the fire, or placed on a grate in a vessel with water that is heated up. The alembic was used in the distillation of essential oils, as well as rose water.

The process begins, of course, with roses. The polymath al-Kindī (ca 801-66), who devoted an entire work to distilling perfumes, started with young fresh red roses, from which the calyxes are removed and the petals spread out and left for a while. Once the roses are dried, they are stuffed inside the cucurbit; as it is heated up, the vapours travel through the anbīq and condense as rose water in the recipient. In the industrial production of rose water, several containers were heated up at the same time.

The Andalusian botanist Ibn al-Awwam al-Ishbilī (12th/13th century) said that Syrian roses are the best for drying and distillation, and recommended immature roses, as they begin to blossom around mid-April. He added that wild roses yield a more fragrant rose water than cultivated ones. The geographer al-Dimashqi (d. 1327) claimed that the rose water produced in his native Damascus was exported far and wide, to the Hejaz, Yemen, Abyssinia, and even to the Indian sub-Continent and China. However, in the culinary literature, rose water made from roses grown in Nisibin (the present-day Turkish city of Nusaybin) is mentioned as being the best.

In medieval Arab cooking, rose water was used not only as a sweetener, but also to rub the sides of the pot at the end of the cooking process. Saffron was often dissolved in it, to colour dishes yellow. Rose water could also be infused with musk, honey or camphor. Chicken dishes, in particular, very often called for rose-water, alongside rose-water syrup, sugar, and various nuts (almonds, mint, pistachios). The Sultan’s Feast contains a few recipes for a meat (lamb) māwardiyya (rose-water stew), which, so the author informs us, was previously known as fālūdhajiyya (fālūdhaj, ‘starch pudding’).

The use of rose water in cooking was, like so many things, a Persian borrowing and, in an interesting lexicological twist, the word for rose water in that language, gulāb (گل, ‘rose’; اب, ‘water’) became the word for rose-water syrup in Arabic (جلاب, jul[l]āb). Later on, the word entered English — through Spanish — as ‘julep’ . Today, rose water is still an integral part of Arab and Persian cuisines, particularly to scent various types of sweets (puddings, pastries, ice-cream), often as a alternative, or alongside, orange-blossom water.

Rose water was also endowed with medicinal properties, and according to Ibn Jazla (11th century) it strenghtened the gums and stomach, soothed eye aches, as well as being an anti-emetic.