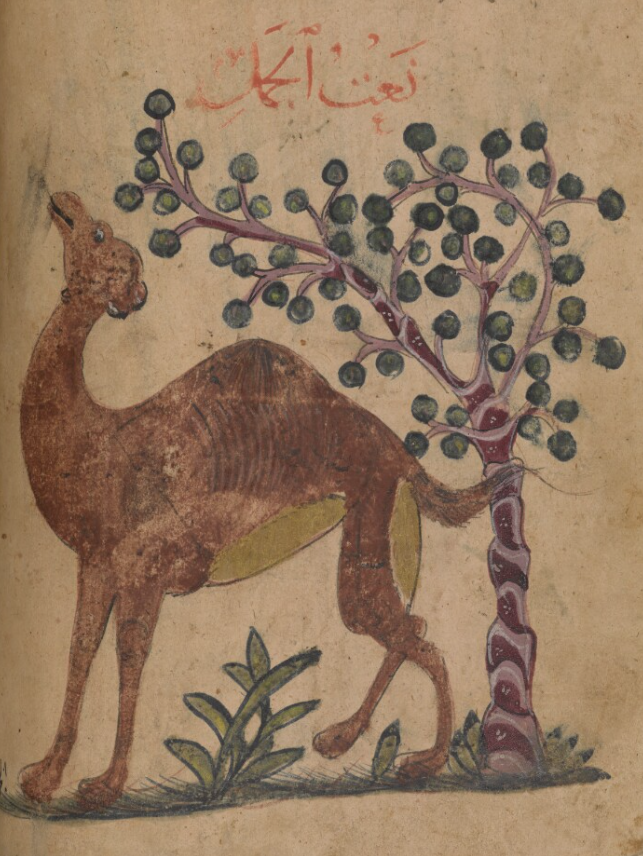

The Arabic words for ‘camel’, jamal and its more classical sister ibil, refer to both the one-humped dromedary (Camelus dromedarius) and the two-humped Camel bactrianus, the so-called Asian camel, which is more common in Persia and Central Asia. The latter species is also called fālij in Arabic. A female camel is known as nāqa, which probably goes back to the Akkadian word with the same meaning, anaqāte.

The animal is already mentioned as food in Classical Antiquity and Greek authors spoke of camels being roasted whole at banquets at Persian courts, whereas Aristotle spoke highly of both camel meat and milk. The Roman emperor Heliogabalus (218-222) was allegedly a great afficianado of camel’s heel, a taste he probably acquired during his childhood in what is today Homs (Syria). Physicians were less favourable, however, and the great Galen stated that only people who were mentally and physically like a camel could eat it.

The Bedouin livelihoods in pre-Islamic Arabia relied on their animal herds, especially the camel, which was their most prized possession due to its multiple uses, as a mount, beast of burden, and a source of drink (its milk), fuel (its dung), and hides. As a result, camels would not usually be slaughtered for meat, unless they were ill or died from natural causes. So, when the pre-Islamic bedouin poet Hatim al-Ta’i (حاتم الطائي) slaughtered several hundred camels to honour visitors, this was considered an extreme act of Bedouin generosity and hospitality. In fact, this and other similar stories — usually involving the slaughtering of animals (especially camels) — made him a legend in Arabic (and Persian) culture, and his name lives on to this day in the saying ‘more generous than Hatim al-Ta’i’ (أكرم من حاتم الطائي).

The camel’s character was not as praiseworthy as its practical benefits and there is frequent mention of its spitefulness and extreme rancorousness, combined with a long memory of those who wronged them!

In Arabic culinary literature, the use of camel meat is only mentioned in what is considered the oldest (10th-century) Abbasid cookery book, which contains a number of camel recipes, known as jazūriyya, from the word jazūr, meaning a slaughtered camel (especially the female). The meat (including the hump) is generally sliced up and cooked (stew or roasted), whereas camel liver also appears as an ingredient. There is also a recipe for a sour drink made from camel’s milk mixed with black pepper and galangal. The author recommended camel milk for liver aches and putrified humours, and its meat for individuals with weak stomachs.

Physicians like Ibn Sina (Avicenna) advised camel’s milk in the treatment of asthma; camel dung for removing scars and warts, pimples, and ulcers, and for swollen joint pains; camel urine for dandruff; camel’s brain with vinegar against epilepsy; camel’s fat for convulsions; and fumigation of a camel’s hump to relieve haemorrhoids. Ibn Bakthishu’ (11th c.) suggested drinking camel’s brain cooked in rainwater in order to combat pains resulting from coldness. Ibn Jazla (12th century), for his part, recommended camel blood against epilepsy, and also includes what is probably the most unusual medicine involving camel; a drink made with dried and crushed camel’s testicles against adder bites — cheers!