Violets Viola odorata), known in Arabic as banafsaj (بنفسج) were used for their medicinal properties in medieval Islamic medicine and were thought to be useful against a wide variety of ailments, including coughs, tumours (when used in a poultice), headaches (when cooked with barley flour), scorpion bites, palpitation, varicose vein, fevers, mumps, toothaches, and haemorrhoids. Some sources refer to the best variety coming from Arjan, in Iran.

The petals of violets were used to make a drink, preserve, syrup, oil, or jam. Violet conserve (مربّى, murabbā) was said to be good for coughs and a coarse throat, though it was also enjoyed by those in good health! Violet oil (دهن, duhn) was used as a soporific or to loosen the joints, especially when made with gourd seeds or sweet almonds.

An Egyptian Mamluk cookery book includes a violet air freshener, known appropriately as ‘banafsajiyya’, made rose water infused with musk and civet. Interestingly enough, the twelfth-century physician Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi commented on the fact that Egyptian violets had an exceptionally sweet scent, but the people in Egypt did not know how to produce oil from it in the proper way, or to preserve it.

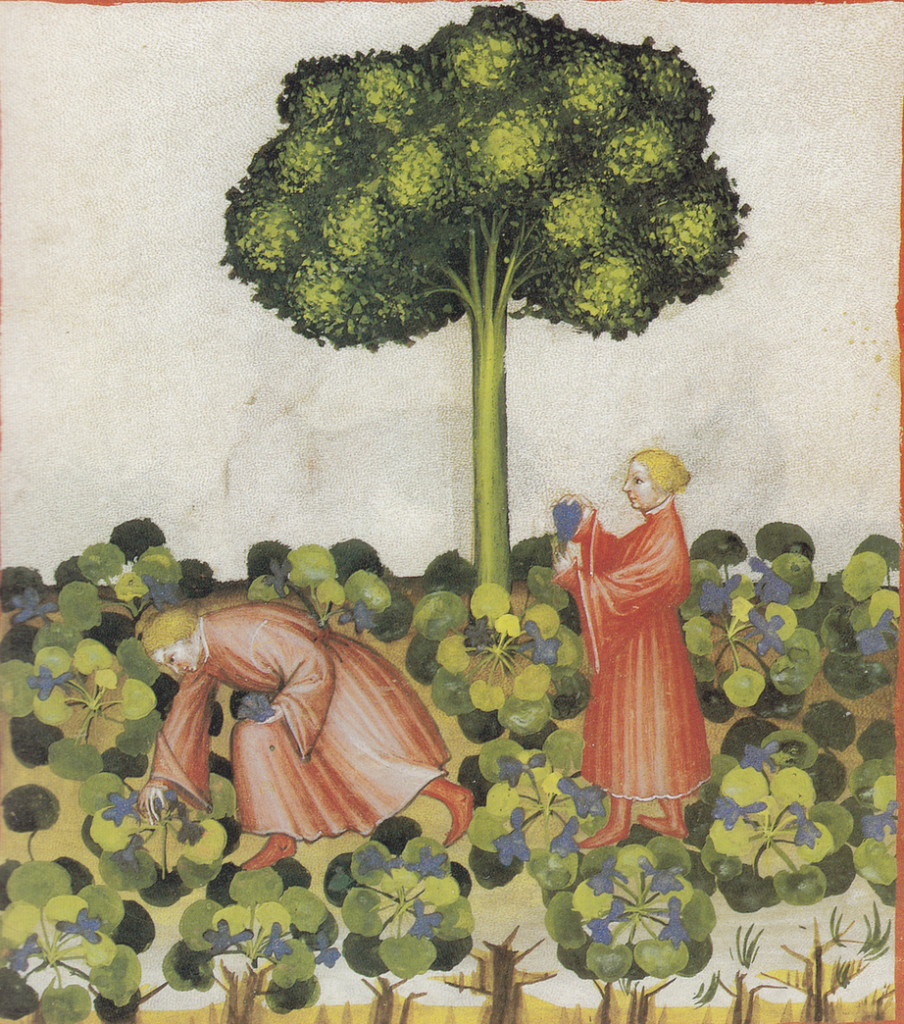

in Medieval Europe, violets were partiuclarly popular for their scent and attractive bright colour, and the leaves and flowers were eaten in salads, as well as in conserves and syrups. Medicinally, they were thought to be cooling and cleansing, and that smelling violets had a calming effect on the nerves. The Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen (d. 1179) gave a recipe for violet oil for curing vision.