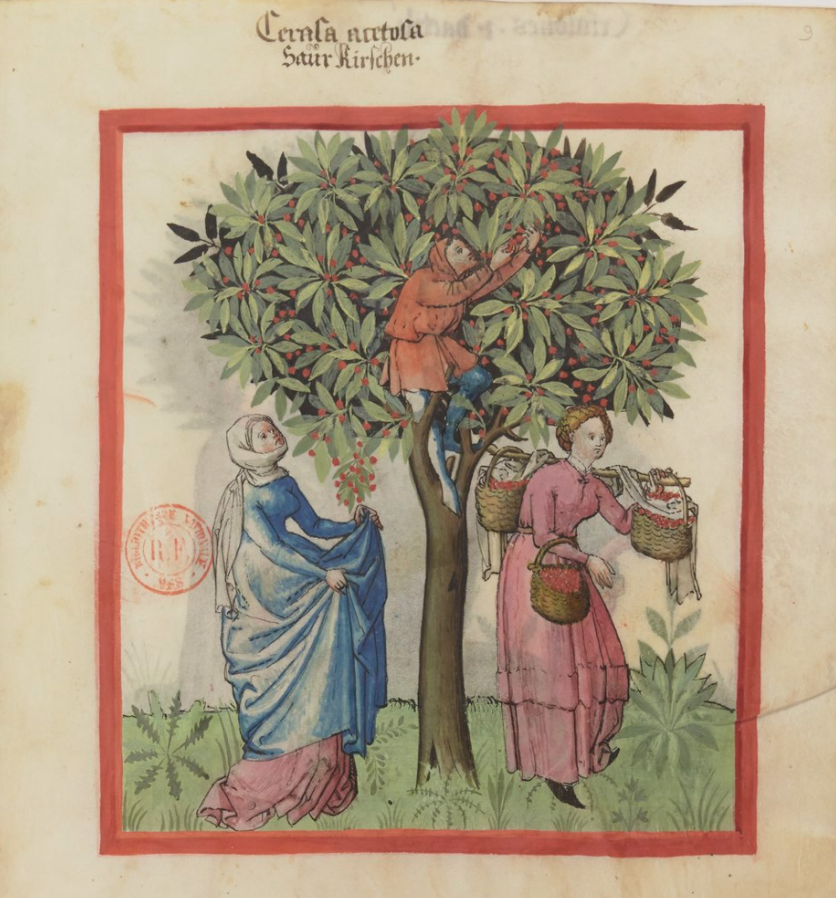

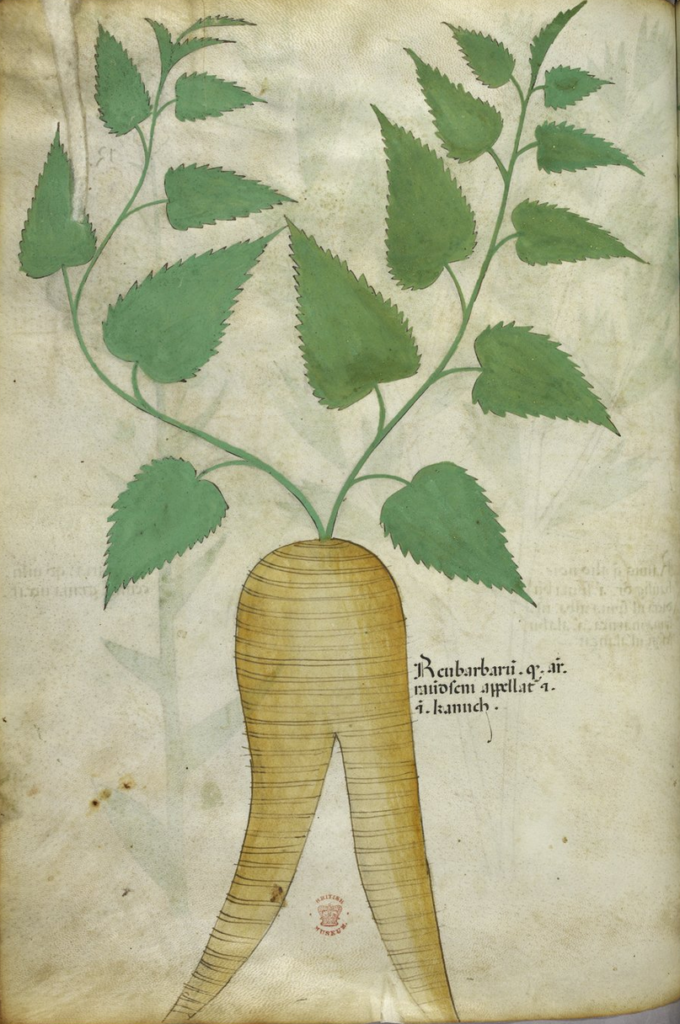

Cherries are native to western Asia and belong to the genus Prunus, which also includes plums, peaches, apricots, and almonds. The wild ancestor of sweet (or ‘bird’) cherries is the Prunus avium, whereas the sour variety goes back to Prunus cerasus. The former was first described in about 300 BCE by the Greek writer Theophrastus.

Sour cherries were imported into Greece from Anatolia and were known in Greek as kerasia (κεράσια), the origin of words in many languages. The Greek word was said to be derived from the name of the town of Kerasousa in Asia Minor (the present-day Turkish city of Giresun).

Dioscorides noted that cherries loosened the bowels when fresh, but had a constipating effect when eaten dried. He recommended the gum of cherry trees in diluted wine brings about healthy looks, sharp-sightedness, and good appetite, as well as being a treatment for chronic cough. The Roman naturalist historian Pliny (1st century) also reports Anatolia as the cherry’s place of origin when they arrived in Rome, and that the fruit was introduced to Britain in AD 47. The Romans must have taken to cherries with great gusto since in Pliny’s day eight varieties of cherry were cultivated in Italy.

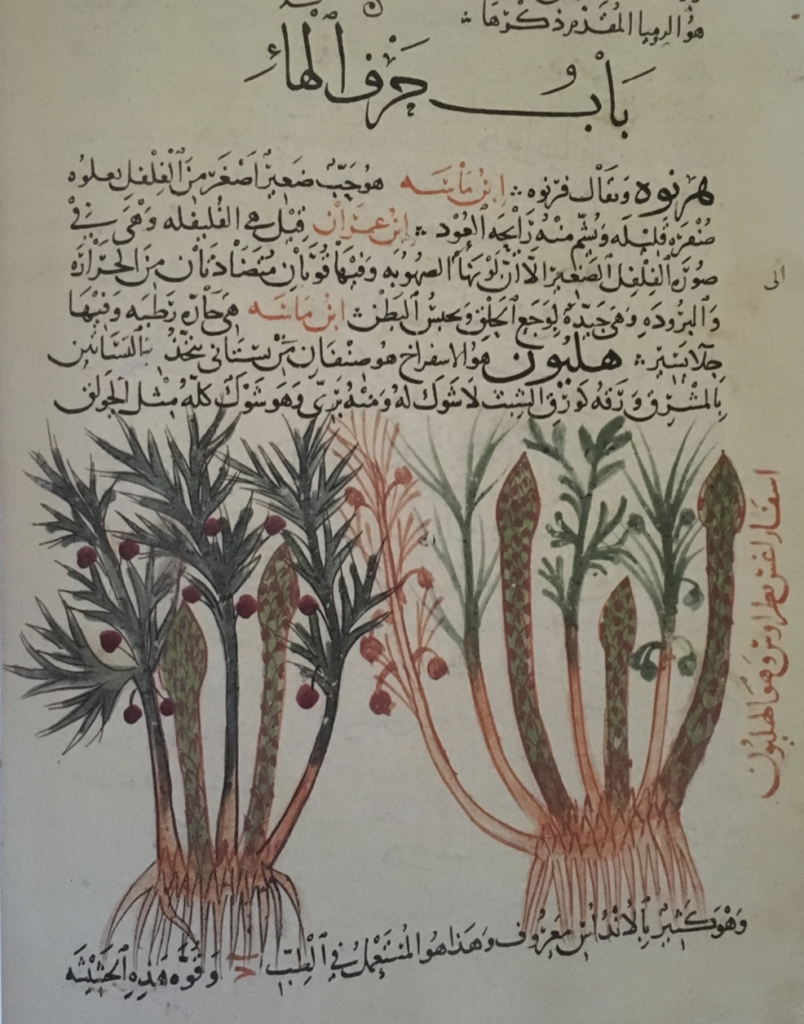

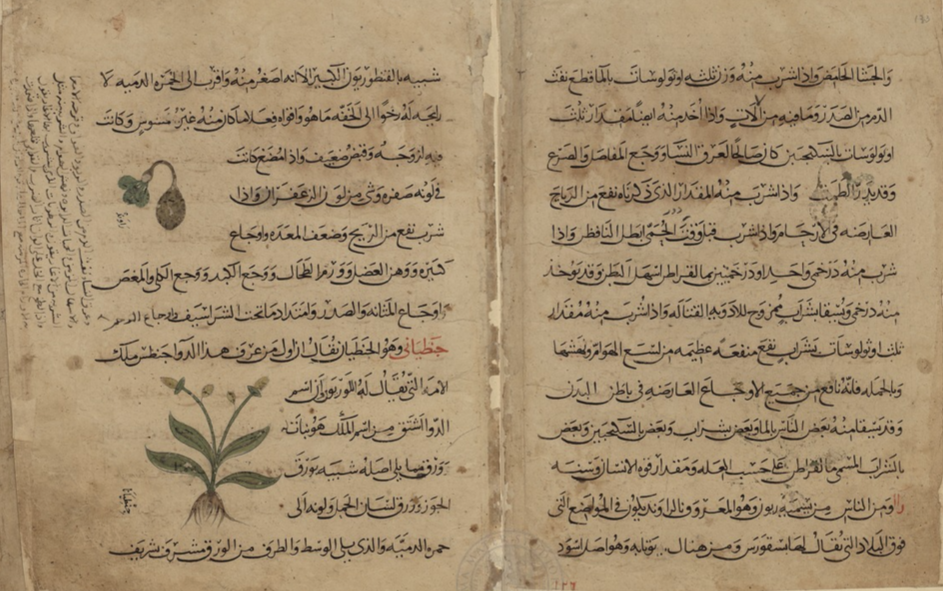

In Arabic sour cherries were known by the borrowing qarāsiyā (قراصيا, قراسيا) or, in the Muslim West as habb al-mulūk (حبّ الملوك), “king’s berries”. They were reported to grow in Syria and Egypt, and one scholar claimed that qarāsiyā was one of ninety plant species growing on Mount Lebanon from which one could make a living by gathering its fruit.

In medieval Arab cooking, they are used very rarely, in a sweet-and-sour chicken stew, of which variant recipes are found in cookery books from Syria (Aleppo) and Egypt (Cairo) dating from the 13th and 15th centuries. Medicinally, they were said to be an aphrodisiac, while Maimonides, who describes qarāsiyā as a plum, but smaller, with a sour taste, claimed that they are a light purgative. According to the physician Dāwud al-Antākī (15thc.), qarāsiyā can be used to treat depression, fainting fits, thirst, cough, loss of memory, internal wounds, and obstructions in the urinary tract.

Today, qarāsiyā refers to a kind of plum in some dialects (e.g. Syria), while in Standard Arabic, the word for cherries is now karaz (كرز).