When the 17th-century Ottoman traveller Evliya Celebi visited Egypt, he noted that firewood was scarce there, and the preserve of the rich. Other people used cow dung as fuel, which he claimed was not as good for cooking, and commonly added natron to the pot to tenderise the meat and other foods, making them cook faster. However, Celebi stated that natron produced harmful effects such as bleary eyes, croaky voices, leprous faces, and hernias in the groin, and bellies that were so extended that it seemed as if the individual was pregnant. He found that most Egyptians suffered from hernias, to the extent that it was considered offensive to address someone as ‘Honoured sir’ (Turkish Behey devletli) as this was a polite way of referring to someone with this condition!

In the medical and pharmacological literature, the terminology is not always consistent as natron (نطرون, natrūn) sometimes also referred to borax (bawraq) or, more commonly, ‘Armenian borax’ (bawraq Armanī). Technically, borax denotes sodium borate, whereas natron is a naturally occurring mixture of sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride (salt) and sodium sulfate. The best variety was mined in Wadi al-Natrun, west of the Egyptian Delta, and was already used in ancient times in the mummification process, as a drying agent. The fame of Egyptian natron was such that it was exported across the Muslim world, and even beyond, to Sicily.

The Swedish naturalist Fredrik Hasselquist, who visited Egypt in the mid-18th century, refers to natrum (sic), as “a salt dug out of a pit or mine, near Mansura in Egypt; it is by the inhabitants called Natrum, being mixt with a Lapis Calcareus (Lime-stone) that ferments with vinegar, of a whitish brown colour. The Egyptians use it, (1.) to put into bread instead of yeast; (2.) To wash linen with it instead of soap. I have been informed, that it is used with success in the tooth-ache, in the manner following: The salt is powdered and put into vinegar, it ferments immediately, and subsides to the bottom. The mouth is washed with this vinegar during the Paroxysm, by which the pain is mitigated, but not taken off entirely.”

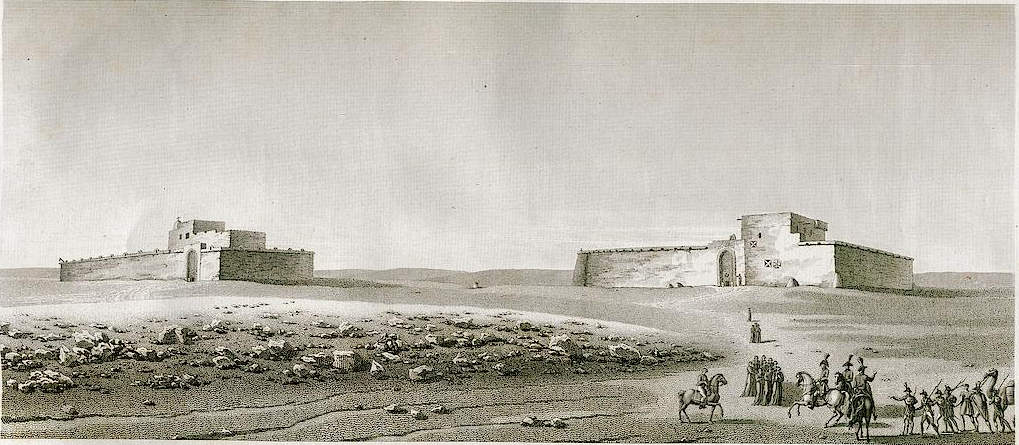

When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, the French reported on flax being bleached in natron for six, eight or ten days, after which it was boiled in a solution of lime and natron, washed in the Nile, and then exposed to the sun. The Egyptians also added natron to tobacco, to keep it moist.

The 8th-century Persian physician Al-Razi (Rhazes) identified six kinds of borax: bread borax, natron, goldsmith’s b., zarawandī, willow’s b., and tinkār (gold solder). Ibn Sina, for his part, only mentions Armenian borax, which is light, brittle, spongy and rosy (or white in colour), and an African variety.

The use of borax to assist the cooking of meat was actually well established, and can already be found in the work of the 11th-century physician Ibn Butlan, who recommended adding borax, wax, and watermelon veins – or its peel – to the pot. The same advice appears in cookery books, such as The Sultan’s Feast, as well. Ibn Sina (Avicenna), warned about the harmful effects of borax on the stomach (which, according to Ibn Jazla, could be counteracted with gum Arabic), but said it could be useful against dandruff and worms. In the medical literature borax appears in recipes for a wide variety of ailments, ranging from fevers, colic and sciatica, to convulsions.

In ancient Greece, where natron was known as nitron, it was used in cooking quite early, and the botanist Theophrastus (371-287 BCE) already referred to cabbage being boiled in it to improve its flavour. In addition, it may also have been used to preserve the colour, as 14th and 15h-century Egyptian cookery books recommend boiling turnip, beans, cabbage, wild mustard, and chard in it to keep them green. One of the cookery books also uses natron in a few sweets, as well as in a hummus mash. The 15th-century blind physician Da’ud al-Antaki claimed that the best kind of of natron was that which had been ‘roasted’ (mashwī), which already appears as an ingredient in qata’if batter, as an alternative to borax, in a 13th-century Syrian cookbook. Interestingly enough, though natron was an ingredient in Qahiriyya recipes of the 13th and 14th centuries, it is conspicuous by its absence in a 15th- century one.

Medieval Arabic cookery books also mention borax for a variety of uses, as a bread glaze (after dissolving it in water), a leavening agent in dough, in handwashing powders, and even – though very rarely — as a food ingredient (e.g. in a sour-milk stew).