This refreshing beverage from 13th-century Muslim Spain is made with fresh violet flowers that are boiled to extract their essence. After straining, sugar is added and this is cooked down to a syrup. Water it down with half the amount of hot water and it is ready to drink. Althrough primarily a medicine against fever and coughs, it has a wonderfully delicate taste which makes it a perfect summer drink as welll.

One eel of a dish…

The recipe this week is truly an exceptional treat, since it is the only one in the Arabic culinary tradition for an eel (سلباح, silbāḥ) dish. Preparation is key and not for the faint-hearted as someone needs to scrape off the skin and gut the critter — though you can always ask your friendly local fishmonger to do the squeamish bit for you. Once that is done, it’s time to cook it in water (not too much), salt, lashings of olive oil and many of the usual goodies, like pepper, cumin, saffron, vinegar, and garlic. When the liquid has been absorbed, put it in the oven for browning. And voilà, ‘eel à l’andalouse‘ 13th-century style! As the author of the cookery book tends to say at the end of each recipe: Eat and enjoy! For accompaniment, keep it simple with some fine olives and bread.

Talk on medicine and food

Check out the CoReMa 2021 Conference where I joined Profs. Alan Grieco and Wendy Pfeffer for a very interesting session entitled ‘Cookery or Medicine?’, and discussed the links between medicine and food in the medieval Arabic culinary tradition.

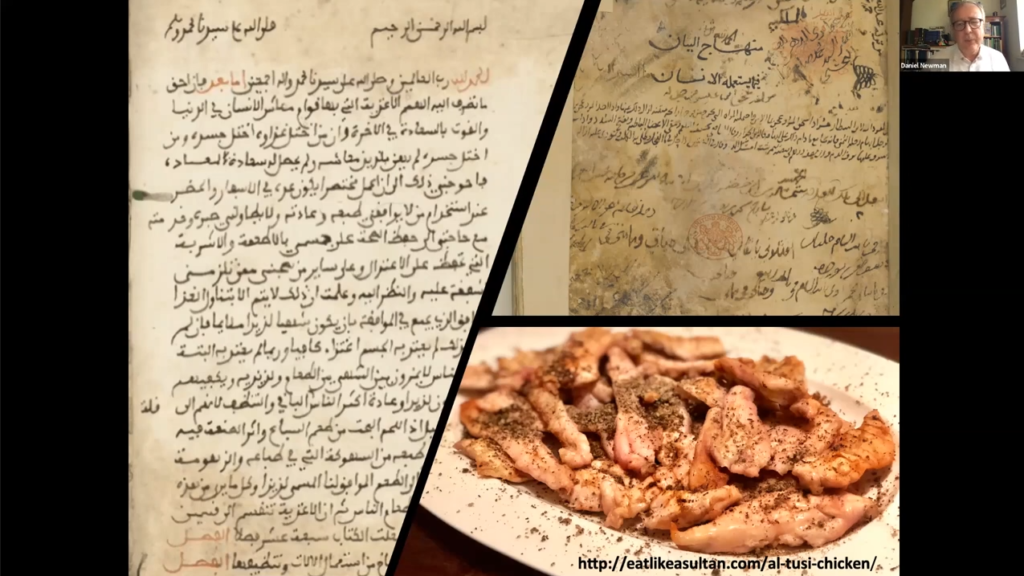

Ibrahimiyya (rose syrup chicken)

This is one of many mediaeval dishes named after (or created by) the gastronome caliph Ibrahim al-Mahdi (779-839). What is unusual is that this one comes from Andalusia. It is chicken (though you can also use lamb, if you wish) in a sauce of rose syrup with olive oil, vinegar, sugar, pepper, saffron, coriander, salt, and a little bit of onion. Peeled and broken up almonds, pistachios, spikenard and cloves are sprinkled on before ‘crusting’ the dish with a mixture of flour, rose water, camphor, and eggs. The result is a wonderfully tangy symphony of sweet-and-sour flavours.

Andalusian fish meets fish…

A delicious fish recipe by the 13th-century Andalusian exile in Tunisia, Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī. It involves garnishing fried fish with… another fish. The garnish is made by mashing fish meat and then mixing it with flour, salt, and pepper. This mixture is then shaped into balls which are cooked with pepper, dried coriander, coriander juice, oregano, and crushed garlic. Then the dish is ‘crusted’ with breadcrumbs and eggs, on top of which you add yolks for decoration. Once you have fried some fish, the fish balls and other ingredients are arranged over them. It goes wonderfully well with the recently made bread.

The Qadi’s biscuits (كَعْك, ka’k)

This medieval Egyptian biscuit is so delicious that it was considered an appropriate gift for visiting grandees. It requires flour, pistachios, sugar, and both chicken fat and sheep’s tail fat, but in the absence of the latter, the re-creation (from The Sultan’s Feast) used only the former. Another interesting twist is that the fat, which is kneaded into the dough, should be rubbed with mastic, cinnamon, musk, and camphor, added with a drizzle of lime juice. Once the dough is finished, make biscuit shapes and bake in the oven until golden. The addition of a pine nut on top just tied it all together!

Stamped Andalusian bread

A 13th-century recipe for a bread you can either make with white flour or semolina. Add yeast, salt and warm water, and knead into loaves of your choosing ; for the recreation it was decided to make small round ones. Leave to rise before baking, and that’s it! In addition, they are stamped with home-made bread stamps. The stamping of food goes back to Antiquity and was also widely used in the medieval Muslim world, often to mark ownership (think of the famous apple in the Arabian Nights story of the Three Apples), or simply as a gimmick, when it could involve an animal, a saying, etc. (which would also be extended to tableware). Two of the stamps contain text: كُل هَنِيئًا (kul hani’an, ‘Eat and enjoy’, i.e. bon appétit) and وليمة السلطان (walīmat al-sultān, ‘the Sultan’s Feast’). The third and fourth stamps represent a gazelle and a geometric design, respectively.

Tuniso-Andalusian battered fried fish

Known as ‘the protected one’ (المُغَفَّر, al-mughaffar) for reasons that will become clear, this recipe is included in the cookbook of a 13th-century Andalusian exile who settled in Tunisia. It is made with fish fillets, which are coated with a batter made of eggs and murrī (as usual, use soya sauce, instead) before coating them with flour, breadcrumbs and a number of spices, including pepper, cinnamon, ginger, coriander, and saffron. Then the fish is fried in a pan until golden brown. There is also a sauce that goes with it, which is made with vinegar, olive oil and murrī.

It is not too fanciful to link this preparation with the British ‘fish and chips’, with even the traditional accompaniment (vinegar), being included! And so, this may well be the oldest recipe for that British classic — without the chips, of course! Further proof about the historical link is provided by the fact that this method of frying fish was imported into England by Sephardic Jewish immigrants from the Iberian Peninsula in the 16th century.

The Sultan’s Feast at the Sant Jordi in New York City festival

Andalusian stuffed eggs (بَيْض مَحْشُو, bayḍ maḥshū)

Eggs were a particular favourite in Muslim Spain, as attested by the many recipes that require them. This delightful 13th-century dish is an egg stuffed with … egg! After boiling the eggs, the yolks are removed and then beaten together with various spices to make a paste, which is then stuffed inside the eggs before frying them in olive oil. Sprinkle on rue, spikenard and cinnamon before serving.