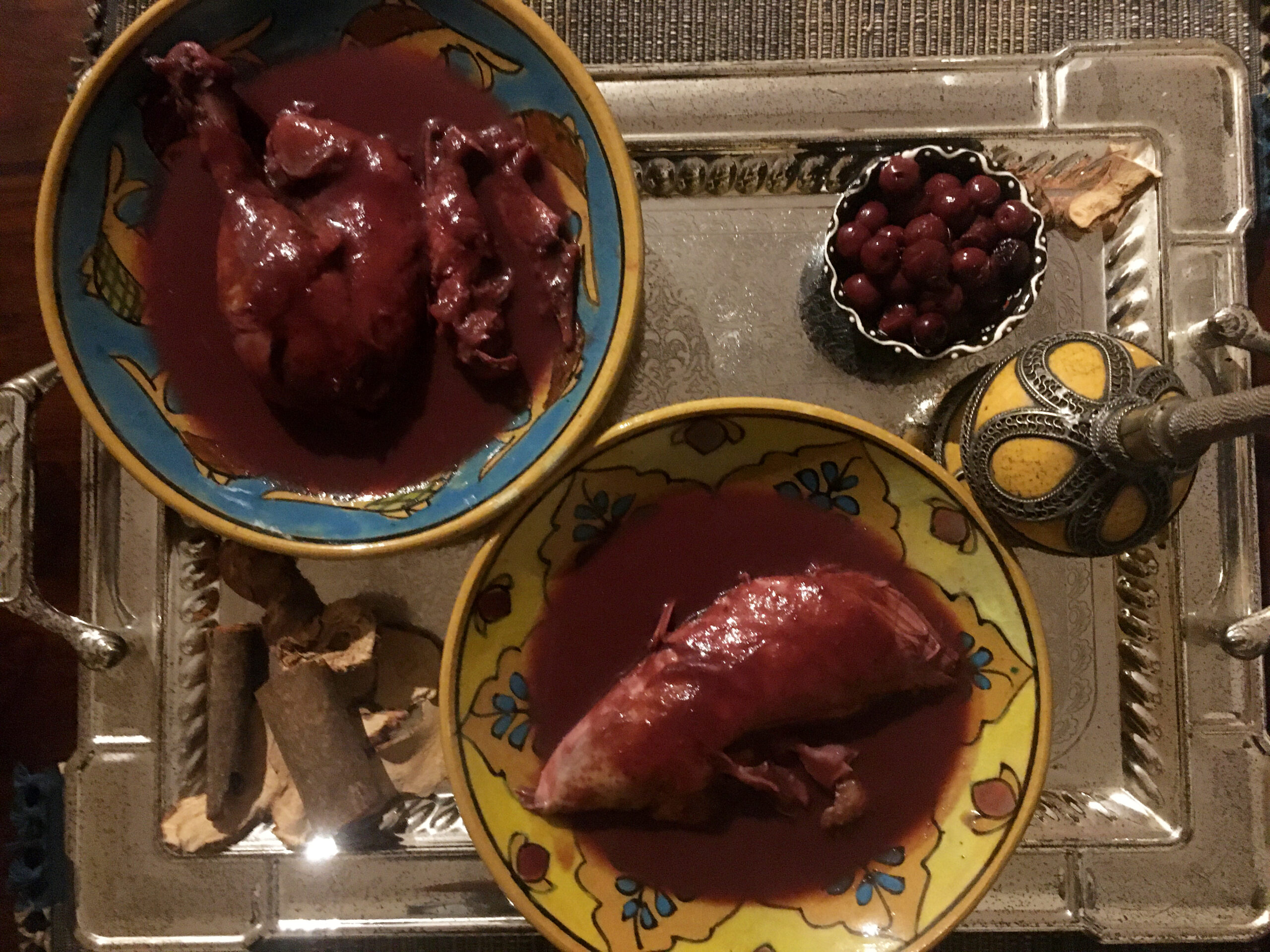

Though the instructions simply say getting some soft-dough bread from the baker, this re-creation is made with a bread recipe from the same 13th-century Syrian cookery book. That will be the object of the next post, but here we’ll be talking about the filling of the sandwiches, which the author claims were Egyptian in origin.

Start by hollowing out small loaves — you can choose the size you like, but it works best if you shape them into large rolls. The main ingredient is the chicken which should be boiled, fried and shredded before mixing it with the crumbs taken out of the bread, pistachios, parsley, mint and lemon juice. Then stuff the mixture into the loaves, thus making them whole again. Cut into pieces or slices of your liking and, perhaps in reference to their Egyptian origins, pile them up into a pyramid, which is then liberally sprinkled with herbs, as well as violets and narcissus, and garnished with orange. Tuck in immediately, though they are still delicious after a night in the fridge.

According to the author this is one of the most elegant foods (فإنّها من أظرف المآكل) and anyone trying these sandwiches will surely agree!