The opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) is a member of the plant genus Papaver and is native to the western Mediterranean, spanning Spain, Italy, and North Africa. It was cultivated in prehistoric Europe and spread widely through Eurasia. Although best known today for its opiate derivatives, poppy leaves, the seeds and their oil are non-narcotic and have long been incorporated into both medicine and food. The common poppy, Papaver rhoeas was also grown for oil.

Classical and medieval sources distinguished between several types: the white, cultivated poppy, which was preferred for culinary use due to its low narcotic properties; and black –often wild variety.

The poppy was already used in cooking by the Romans and Greeks, and the seeds were commonly poppy seeds sprinkled on bread before baking. Their status as a luxury ingredient is evidenced by their use is in a dish of dormice rolled in honey and poppy seeds, which was on the menu at the famous ‘Trimalchio’s Dinner’ (Cena Trimalchionis) in Petronius’ picaresque novel Satyricon (1st century CE), which describes the extravagant cuisine of the upper classes in Rome. Galen describes their use alongside sesame seeds, praising the whiter seeds for their taste and soporific effects, although he notes they are nutritionally negligible and difficult to digest.

In Arabic, the term for poppy is khashkhāsh (خشخاش) and in medieval Arabic cuisine, the seeds (both ground and whole) — especially the white variety— were widely used, especially in Mamluk (Egyptian) cookery books (some thirty recipes). Poppy seeds are called for in a variety of recipes, for instance in sweets (puddings, candy, biscuits, and halva), meat stews (e.g. with dates, raisins), judhabas (drip puddings), pickles, and beverages. In one gourd-based sweetmeat, the author explicitly recommends adding as many poppy seeds as possible to cause sleep, revealing both culinary and pharmacological intent. Sometimes the seeds could be toasted and used as garnish.

In the medicinal literature, where the black poppy was preferred, the seeds were used in a variety of recipes, as in the famous formulary by Sabur Ibn Sahl (9th c.), for robs (ربّ, rubb; syrups), lohochs (لعوق, la’ūq; lick medicines), pastilles (قرص, qurs), powders (سفوف, safūf), poultices (ضماد, ḍimād), and decoctions (مطبوخ, matbūkh). The conditions are very varied, ranging from coughing and pains in the kidney and bladder to hepatic fever), and even consumption. Maimonides considered poppy seeds non-harmful when used in moderation, and cautioned against head heaviness and excessive consumption, which induces drowsiness. Physicians held that poppies provide little nourishment, and cause constipation. However, when taken with honey, it had aphrodisiac properties since it was thought to increase semen. This also explains why poppy seeds often co-occur with honey in recipes.

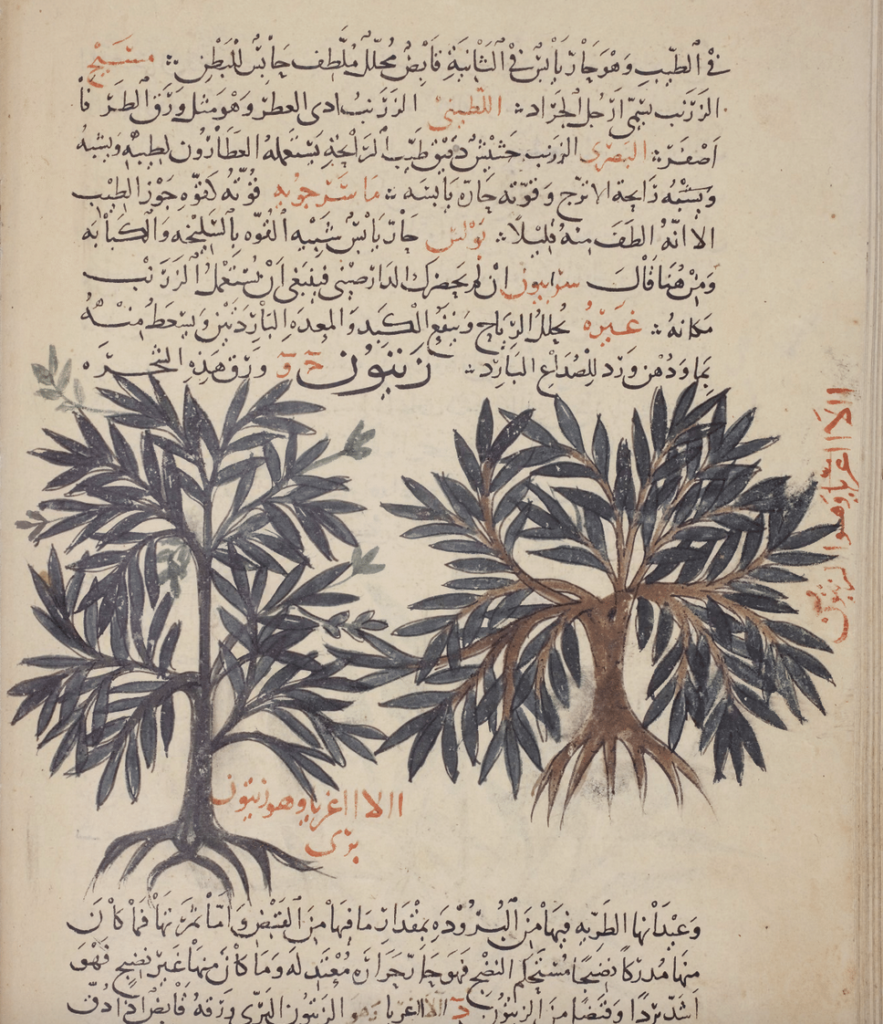

The poppy in the Vienna Dioscorides codex